Engagement Party

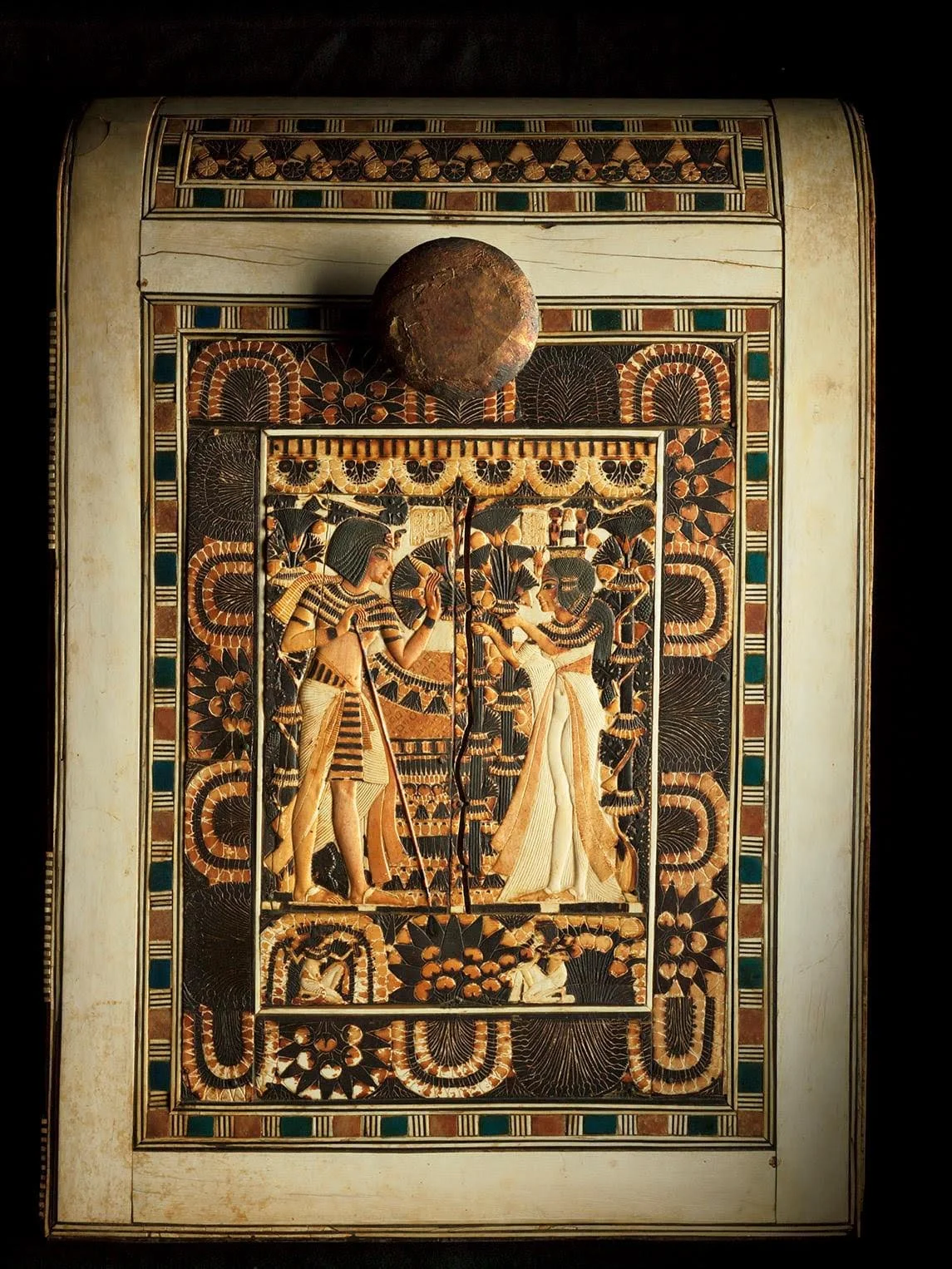

Figure 1. Tutankhamun and his wife Ankhesenamun in a garden (Egyptian Museum Cairo).

We grew up together, our mothers were different but the pharaoh was our father, but there were so many mothers and children by our father it was hard to keep track. We were born in a strange time, when the Aten was revered and gardens surrounded us. Much of this changed after our father died, it seemed that there was a last gasp while Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten held onto power. But we were so young; we had played as children days before. My playmate and betrothed was made king, he was only nine. The priests controlled everything and they were planning to move our house from Amarna to Memphis, the new capital city, our names would change, and they moved forward with our wedding.

It was too rushed. We had been promised to each other for so long, but they wanted him to be settled and produce heirs. I felt like the love we held for each other was being taken away, and I wanted it back. Tut couldn’t run much, he always needed a cane to get around. I liked running back and forth and tried to make sure he didn’t feel left behind. He often looked a bit sad but held his good humour. I brought him to our favorite hiding spot in the vast gardens one morning. I told him he should sit, but he refused, just leaning against his cane, being just as stubborn as usual. I shrugged and told him I’d be right back, darting off to the areas I’d mentally mapped to collect a bundle of papyrus in one hand and a collection of water lilies in the other. Walking back to our spot he just watched as I turned the corner and slowly presented the plants to my king, my betrothed, my friend, my Tut.

“You were born to rule, you are the new embodiment of Horus. You will keep Kemet together,” I held out the papyrus. “The wadj for the flourishing Upper Tjufy and…” holding up the lotuses, “the seshen for the rejuvenating Lower Tjufy. Whatever gods we have and follow won’t change that you are beloved by them or by me.” I took a breath for what felt like the first time since I walked in. “I -” He held up his hand and my voice froze. Tut smiled, took my hand, and lowered it to see my face.

“I love you and am devoted to you, not only Kemet, and I am so glad you want to be my great royal wife and queen. We’ll live happily and long, I promise.”

We spent time collecting flowers in the garden, playing, and hiding from our royal duties for as long as we could, but of course that couldn’t last forever.

But of course, it didn’t. The couple had children, both stillborn daughters prematurely at 5-6 months and King Tutankhamun died at age 18, leaving his (approximately) 20ish (maybe) year-old wife alone who likely had to marry his successor and her maternal grandfather, Ay.

This is a fictional retelling of the painting on the lid of an ivory box found in Tutankhamun’s burial chamber. We can’t know what happened, how he and his royal wife grew up, how they got engaged, or if they did anything. But a picture tells 1000 words. Of course, marriage is and was a contract to connect family lines and houses, keep money in the family and the blood pure, and keep women as property. With all those fine to ill-conceived reasons for marriage, this art may have shown something different: love. Ahh, young love.

King Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun's engagement was not the first marriage proposal depicted in ancient Egyptian art. King Tut's mother was also shown in the older Amarna style proposing to her future husband, King Akhenaten. A contrast shows up later in the returning Classic Egyptian style in which Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun are painted. These painted artifacts were found in the Tomb of King Tut, rediscovered by Howard Carter in 1922 in the Valley of the Kings outside of Karnak, Luxor.

“Although its ornamentation comprises an ivory veneer, beautifully carved in relief and stained with simple colors, it has borders of encrusted faience and semi-translucent calcite.

The central panel of the lid is the unsigned work of a master and as a contradiction to the warlike scenes to show off the prowess of the king, the motive here is purely domestic. It depicts the young king and queen in a pavilion covered with vines and flowers. The royal couple wearing semi-court attire face one another; the king leaning slightly on his staff accepts bouquets of papyrus and lotus blooms from his consort or fiancé; while in a frieze below two court maidens gather flowers and the fruit.

Above their Majesties are short inscriptions:

‘The beautiful God, Lord of the Two Lands, Nebkheprure, Tutankhamen, Prince of the Southern Heliopolis, resembling Re.’

‘The Great Royal Wife, Lady of The Two Lands, Ankhesenamen, May she live.’

Figure 2. Box with Carved Scenes of Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun. Egyptian Museum, Cairo. JE 61477

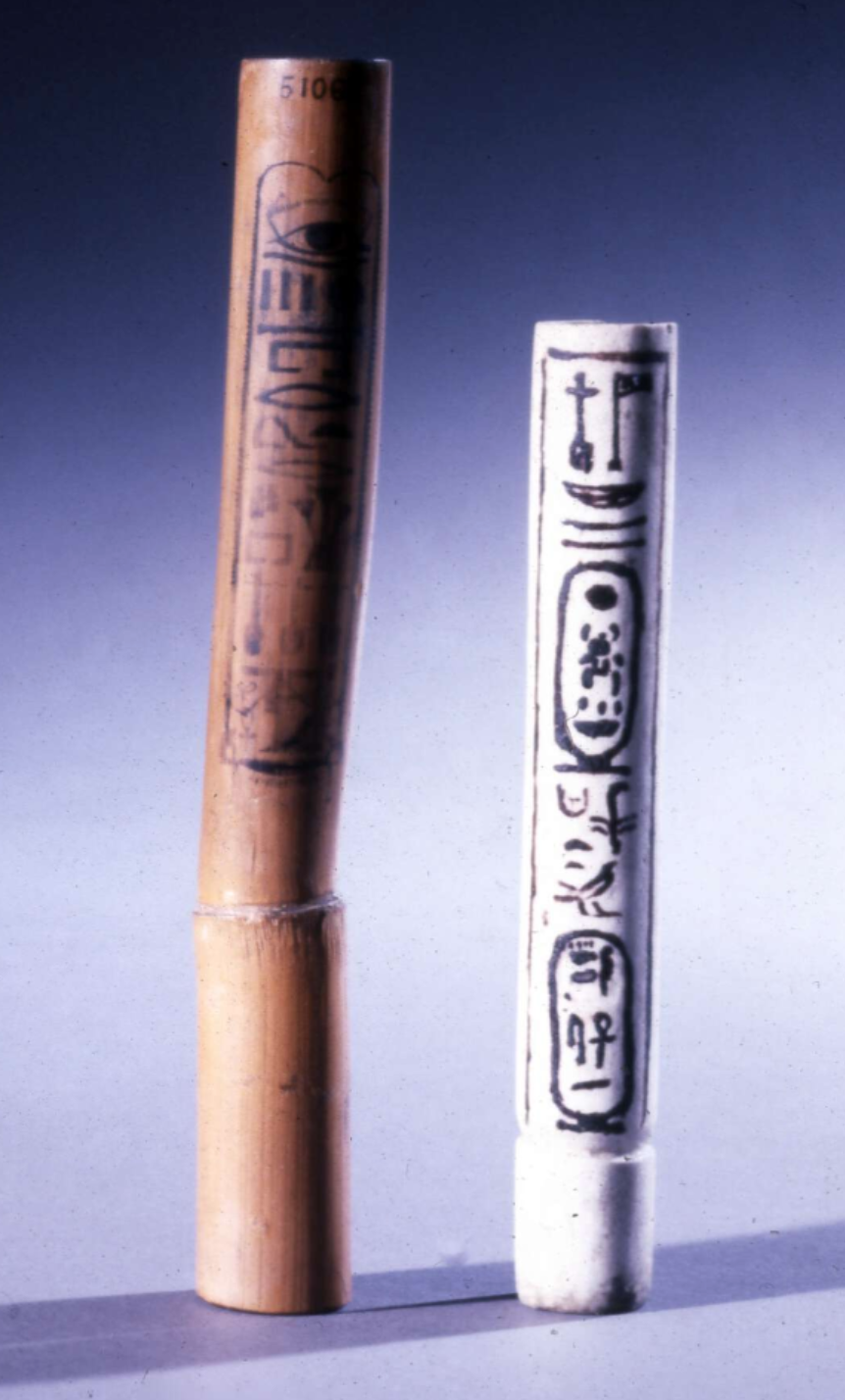

Figure 3. White glazed composition kohl-tube bearing the names of Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun. British Museum. EA2573

*Since the Naqada III era (c. 3100 BC), Egyptians of every socioeconomic class have used kohl, which was originally used to guard the eyes. It is also believed that darkening around the eyes protects the delicate skin of the eyelid from the sun’s rays along with the stickiness catching sand and bugs.

The subjects of the side and end panels pertain to the chase, their compositions being friezes of animals, and the king and queen fowling and fishing. When found in the tomb, the case contained sandals, cult robes, necklaces, a headrest, and a belt.

Stele Style

Figure 4. Walk in the Garden; limestone; New Kingdom, 18th dynasty, c. 1335 BC. Egyptian Museum Berlin, Inv. no. 15000 (donated by James Simon in 1920).

Figure 5. A casual scene depiction of Akhenaten and his family.

A relief of a royal couple in the Amarna style; figures have variously been attributed as Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Smenkhkare and Meritaten, but likely should be identified as Tutankhamen and Ankhesenamen, since the relief dates to after the former king's death (Clayton 2006: 120). In either case, it would have been carved earlier, in the 'realistic' Amara style of the period. They are shown wearing wigs/crowns, shoulder-beaded necklaces, and fancy robes, and Akhenaten/Tut is leaning on a blue staff (making it match more with Tut since he needed a cane) while Nefertiti/Ankhesenamun is holding plants. The blue-colored hair could connect with the belief that Lapis Lazuli, one of the stones used to create the pigment (Dodson 2009: 30), was the hair of the gods (Ridley 2019: 337, 345). It could also have to do with being the color of life, rebirth, and knowledge, from the Gods Osiris and Thoth, Goddesses Nun and Ma'at, and the Nile itself. It could also have to do with the color blue being closer to black, which would have been the hair color. It works either way. Both headdresses are adorned with the snake goddess Wdjt, the protector of the Pharaoh. Both of the characters are wearing royal dress styles, the light linen fabric showing off the difference in body design and only the male is wearing sandals. This would show that the characters are of high class and that this moment would have been a special occasion.

Figure 6. The original art piece on the box (above) can be seen in the New Cairo Museum in Cairo, Egypt. (Photo taken by me in the (old) Cairo Museum in 2016). (c. 1357 1349 BC) 18th dynasty

Comparing to the lid, the painting on the box (Figures 1 & 5) shows the same event as the carved and painted stele, but the box’s art is in the classic Ancient Egyptian style which is made to look more stiff, regal, and perfect. King Tutankhamun is in a garden with Queen Ankhesenamun. The costumes, jewellery, and hairstyles of the couple are clearly depicted and differenciated. It adjusts the clothing and accessories with black hair wigs on both people, a large headdress on top of Ankhesenamun's wig, and a perfumed oil cone in her hair. King Tut stood up straight while still holding his staff, rather than slightly slouched and Ankhesenamun holding bunches of lotus flowers and mandragora bulbs in her hands in front of her in offering, instead of casually holding them out on either side.

In both art styles, the plants that the woman is holding are gifts to her 'future' husband, the lotus flower in her left hand and the papyrus reed in her right. The meaning of the marriage proposal is all depicted from Ankhesenamun's perspective. She is presenting Tut the lotus, the symbol of Lower Egypt - where the Northern delta is, and the papyrus reeds, the symbol of Upper Egypt - the Southern, more mountainous area.This is done to show the continuing union of the two halves of the kingdom, as one could see in the Pschent, the combination crown (Figures 7-9).

Figure 10. Map of Ancient Egypt (can buy at https://www.theexploresspodcast.com/store/ladycentric-map-of-ancient-egypt)

Memphis, Capital of Ancient Egypt

This art piece is meant a sweet backdrop of what was written to be a marriage with love at its core, and shows that women can propose too (#ancientfeminism)? [especially if they don't have much choice anyway].

Unfortunately, this didn't directly translate to the couples' lives together. While being manipulated by their government officials and priests, half-siblings Tut and Ankhesenamun had two daughters (Marriage in Ancient Egypt, 2024). They were both were still-born, either born prematurely or near full term, problems possibly due to the level of incest involved with both parties. They were both mummified and also can be found in the Cairo Museum, labelled as pieces 317A and 317B (Reeves 1990). The genetic analysis of their offspring revealed severe health issues, including Sprengel's deformity, spina bifida, and scoliosis, providing stark evidence of the biological cost of maintaining supposedly pure royal bloodlines (Ankhesenamun Was King Tut’s Wife — And His Half-Sister, 2023). These losses were not merely personal tragedies but had significant implications for the stability of the Egyptian throne.

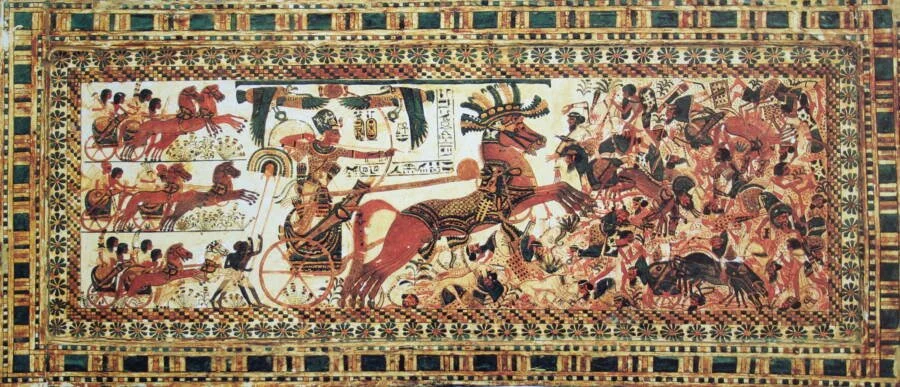

Along with the newly reinstated 'Classic Egyptian' body position style which returned with Tut's rise to power. His father, Akhenaten was banished and or died, and his mother Nefertiti possibly changed her name to Smenkhkare (Clayton 2006: 120) to distance herself from her previous co-reagent or was replaced earlier on during Akhenaten's reign or after dying (DeLong 2023). Archaeologists are still arguing about all of this, along with why Tut would be shown with a staff, whether he had a clubbed foot (which it looks like he did), and how he died. Theories abound, but the main one started with the interpretation of propaganda art in a stele showing Tut riding on a chariot (Figure 11). It was thought that he died from an infection after a chariot injury gone wrong fractured his leg and damaged his pelvis, and that infection led to blood poisoning, but this is unlikely. The prevailing theory is that, yes, he was born with a club foot and was born just being generally unhealthy with physical impairments due to the level of incest issues through the generations. So, did not do any of the chariot racing or army leading that he was shown doing on paintings and stele, and died of a gangrene infection at the young age of 19 after likely having so many bouts of malaria. Meanwhile, Ankhesenamun was forced to marry the next Pharaoh after Tut, one of his aging advisors named Ay, who also may have been her grandfather, though data is unclear, and she finally disappears from the record between 1325 and 1321 BCE.

Figure 11. A depiction of King Tut riding on a war chariot.

The marriage of Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun represents a pivotal moment in ancient Egyptian history, occurring during a period of dramatic religious and cultural transformation. It was not only a personal union but also a strategic alliance aimed at restoring the traditional religious and political order that Akhenaten had disrupted. Their union had a profound impact on the traditions of ancient Egypt, particularly in the context of royal marriages and their societal implications. It not only reinforced existing customs but also contributed to the evolution of marriage practices within the broader Egyptian culture. Their union symbolized a return to the established norms of royal marriages, which often included sibling unions to preserve the purity of the royal bloodline and consolidate power within the family (Zapletniuk, 2021; Habicht et al., 2015; Hawass et al., 2010). These established royal traditions of interfamilial marriage emerged complex circumstances that would influence both their reign and Egyptian society as a whole. As half-siblings their relationship exemplified the delicate balance between maintaining royal bloodlines and navigating political, cultural, and social traditions (Ankhesenamun Was King Tut’s Wife — And His Half-Sister, 2023).

Time Changes

In the Pre-Amarna period, marriages among the elite, particularly within the royal family, were often politically motivated alliances designed to consolidate power and maintain dynastic continuity. Marriages frequently occurred between siblings or close relatives to preserve the purity of the royal bloodline, a practice that was deeply entrenched in the cultural and religious beliefs of ancient Egypt (Zapletniuk, 2021; Habicht et al., 2015). The unions were characterized by a strong emphasis on familial ties, with the expectation that royal couples would produce heirs to secure the throne. This practice was not only a matter of political strategy but also a reflection of the divine nature attributed to the pharaohs, who were believed to be gods on earth (Hawass et al., 2010; Kawai, 2010).

During the Amarna period, initiated by Akhenaten, the nature of marriage underwent a radical shift. Akhenaten's reign was marked by a significant departure from traditional religious practices, including the worship of the Aten over the established pantheon of gods. This shift extended to the royal household, where the emphasis was on monogamous marriage with a single queen, Nefertiti. The Amarna period saw a redefinition of royal marriage, where the focus was placed on the individual relationship between the king and queen, rather than on broader political alliances (He, 2023; Onstine, 2010). The later change reflected Akhenaten's revolutionary approach to governance and religion, which ultimately led to social upheaval and a breakdown of traditional structures which were then rebuilt. Their names themselves reflect this transition - Tutankhaten became Tutankhamun, and Ankhesenpaaten became Ankhesenamun, both changes symbolizing the return to traditional religious practices (Ankhesenamun Was King Tut’s Wife — And His Half-Sister, 2023).

The Foundations of Royal Marriage

Ancient Egyptian marriage customs generally prohibited unions between close relatives, except within the royal family, where such practices were not only accepted but expected (Marriage in Ancient Egypt, 2024). This exception stemmed from the deeply held belief that royal blood carried divine essence, with ruling families claiming descent from the gods themselves and the gods always kept it in the family to ensure the continuation of divine lineage and the stability of the monarchy.(Ankhesenamun Was King Tut’s Wife — And His Half-Sister, 2023; Habicht et al., 2015; Hawass et al., 2010).

Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun's marriage occurred when he was approximately ten years old and she was between eight and ten years of age, following the established pattern of early royal marriages (Marriage in Ancient Egypt, 2024). Their union was particularly significant as it represented a continuation of the practice of sibling (well likely half-siblings) marriage within the royal family. Though they shared only a father, Akhenaten, it still preserved the royal bloodline's purity and consolidated power within the family (Zapletniuk, 2021; Habicht et al., 2015; Hawass et al., 2010). (Caroline Hubschmann, 2022).

First and foremost, the marriage between Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun exemplified the political significance of royal unions in ancient Egypt. As they were both of royal lineage their engagement served to legitimize Tutankhamun's reign following the tumultuous period of Akhenaten's rule, thereby reinforcing the importance of dynastic continuity in royal traditions (Amin & Al-Bassusi, 2004; Habicht et al., 2015; Hawass et al., 2010; Onstine, 2010). This was particularly important given that Tutankhamun ascended to the throne at a very young age and faced challenges from various factions within the court, including the powerful vizier Ay, who would later usurp the throne (Zapletniuk, 2021; Kawai, 2010). The wedding celebration itself would have been a public affirmation of their union, serving to rally support among the populace and the nobility, strengthening Tutankhamun's position as pharaoh.

Royal Weddings - Political and Religious Implications

The wedding celebration of Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun also differed significantly from those in the Pre-Amarna and Amarna periods. In the Pre-Amarna era, royal weddings were grand public spectacles that reinforced the power and divine status of the pharaoh. They involved elaborate rituals and ceremonies that showcased the couple's union as a divine mandate (Halawa, 2023; الدین, 2022). In contrast, during the Amarna period, the focus on individual relationships may have led to more private ceremonies, reflecting Akhenaten's emphasis on personal devotion over public display (Mohammed et al., 2014; Walls et al., 2014). However, Tutankhamun's marriage celebration likely reinstated the grandeur and public nature of royal weddings, serving as a means to rally support among the populace and reaffirm the pharaoh's divine right to rule, thereby reinforcing the religious and cultural narratives that underpinned the pharaonic authority. These rituals often involved the exchange of gifts, public ceremonies, and the presence of witnesses, which underscored the communal acknowledgement of the marriage (Halawa, 2023).

Such practices not only solidified the bond between the couple but also reinforced the social fabric of ancient Egyptian society, where marriage was viewed as a sacred contract that upheld familial and societal order. The grandeur of royal weddings set a precedent for subsequent royal marriages, influencing how such unions were celebrated across different classes of society (Lev & Lev-Yadun, 2016). This adherence to tradition was crucial in a society that valued continuity and stability, particularly in the wake of the religious upheaval caused by Akhenaten's reign (He, 2023; Onstine, 2010). In terms of religious significance, the marriage of Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun can be seen as an attempt to restore the worship of the traditional pantheon of gods, which had been overshadowed by Akhenaten's monotheistic worship of Aten. Their union likely involved rituals that invoked the blessings of the gods, thereby re-establishing the divine order that was essential for the pharaoh’s legitimacy (Hawass et al., 2010; Onstine, 2010).

The wedding celebration’s elaborate feasts and public displays served to reinforce the social hierarchy also demonstrated the pharaoh's role as a provider and protector of the people. Such celebrations not only marked significant life events but also reinforced the communal identity and the collective memory of the people (Halawa, 2023; الدین, 2022). The grandeur would have been a demonstration of the wealth and power of the pharaoh, further solidifying his position in the eyes of both the nobility and the common people.

Societial Norms

The engagement and wedding also reflected the broader societal norms regarding gender and power in ancient Egypt. While women in ancient Egypt, including queens like Ankhesenamun, enjoyed a relatively high status compared to their contemporaries in other ancient cultures, they were still largely defined by their relationships with men in a patriarchal society (He, 2023; Khalil et al., 2017). Ankhesenamun's role as queen consort was pivotal; she was not only a political figure but also a symbol of the continuity of the royal lineage. The marriage would have been celebrated not just as a personal union but as a reaffirmation of the societal structure that placed the pharaoh at the center of both political and religious life (He, 2023; محمود, 2021).

The emphasis on fertility and the expectation of producing heirs were also central to the marriage of Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun. This expectation was reflective of broader societal beliefs regarding the importance of lineage and the continuation of the royal line. The rituals surrounding their marriage likely included prayers and offerings to deities for fertility, which would have further reinforced the cultural significance of marriage as a means of ensuring the stability and prosperity of the kingdom.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

Despite the challenges they faced, artistic representations from their reign suggest a genuine affection between the young rulers. Like with their parents, drawings depict them in intimate moments, exchanging gifts and showing physical affection, indicating that even within the constraints of a political marriage, there was room for personal connection (Figures 12 & 13)(Marriage in Ancient Egypt, 2024). These artistic representations served as models for how royal couples should present themselves to their subjects, influencing both elite and common perceptions of marriage (Marriage in Ancient Egypt, 2024).

Furthermore, the socio-political landscape surrounding Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun's marriage was markedly different from that of their predecessors. The aftermath of Akhenaten's reign left a power vacuum and a populace yearning for stability. Tutankhamun's marriage was, therefore, not only a personal union but also a political maneuver to restore faith in the monarchy and the traditional pantheon of gods (Denewer et al., 2011; Ndou-Mammbona & Mavhandu-Mudzusi, 2022). The couple's wedding celebration would have been a public affirmation of their commitment to restoring the old ways, emphasizing the importance of the gods and the traditional religious practices that had been sidelined during the Amarna period.

Figure 12. The golden throne of Tutankhamun with an intimate moment with King Tut and Ankhesenamun depicted in the classical Egyptian style.

Figure 13. Intimate moment of fun hunting activity as a couple in the classic style.

Figure 14. A statue of Ankhesenamun and King Tut at Luxor.

Conclusions

The marriage of King Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun marked a pivotal moment in ancient Egyptian history, signifying a return to traditional practices after a period of upheaval. This union not only served as a strategic maneuver to solidify the royal throne but also reinforced the cultural significance of familial alliances and the divine aspect of royal marriages. Their wedding celebrated both political consolidation and religious restoration, illuminating the complex gender roles and societal dynamics of their time, and emphasizing the enduring relevance of royal marriages in preserving political stability and cultural continuity in ancient Egypt. These elements not only shaped the customs surrounding marriage in ancient Egypt but also reflected the broader cultural values that defined the society.

Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun's marriage exemplified both the strengths and weaknesses of ancient Egyptian royal marriage traditions. While their union reinforced established practices of maintaining royal bloodlines through interfamilial marriage, it also demonstrated the biological dangers that went along with it. Their reign marked a significant period of religious and cultural restoration, with their marriage serving as both a symbol and instrument of these changes. The artistic depictions of their relationship, preserved in tomb artwork and other artifacts, continue to provide valuable insights into ancient Egyptian concepts of royal marriage and its role in maintaining social and political order (Marriage in Ancient Egypt, 2024). Their story may serve as a compelling reminder of how royal marriages in ancient Egypt were not merely personal unions but powerful instruments of political, religious, and cultural change, but if it could be seen as a story then maybe there could’ve been genuine love. They knew eachother for their entire lives, and while they were pushed together for a multitude of reason we can imagine that (especially as incredibally rich and powerful young people who would want for nothing) they could have been living happily as friends or in love - slightly ignoring their siblingness*. They had so many setbacks and literally grew up together. It's a tragically human tale that I'm so glad to share for Valentine's Day. I think what we can learn is that love may start easy and beautiful, but it's a struggle, just the rest of real life. The crazy truth that love and marriage and kids don't make everything automatically better is much more reminiscent of the history of the real St. Valentine.

*Still a better love story than Twilight and all subsequent fanfiction films.

More About:

The chemistry of the ancient color blue

The history of Valentine's Day

References:

Al-Khafif, G. and El-Banna, R. (2015). Reconstructing ancient egyptian diet through bone elemental analysis using libs (qubbet el hawa cemetery). Biomed Research International, 2015, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/281056

Allen, T. (2000). Problems in egyptology. Journal of Black Studies, 31(2), 139-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/002193470003100201

Amin, S. and Al-Bassusi, N. (2004). Education, wage work, and marriage: perspectives of egyptian working women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(5), 1287-1299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00093.x

Ankhesenamun & Zannanza: A Marriage Alliance Hindered by Murder. (2022). https://www.thecollector.com/ankhesenamun-and-zannanza/

Ankhesenamun Was King Tut’s Wife — And His Half-Sister. (2023). https://allthatsinteresting.com/ankhesenamun

Clayton, P. (2006) Chronicle of the Pharaohs. Thames and Hudson. p.120.

DeLong, William. April 29, 2023. "Inside The Tragic Life Of Ankhesenamun, The Wife Of King Tut." AllThatsInteresting.com. https://allthatsinteresting.com/ankhesenamun. Accessed January 17, 2025.

Dodson, Aidan (2009). Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-304-3.

Denewer, A., Farouk, O., Kotb, S., El-khalek, S., & Shetiwy, M. (2011). Quality of life among egyptian women with breast cancer after sparing mastectomy and immediate autologous breast reconstruction: a comparative study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 133(2), 537-544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-011-1792-8

Habicht, M., Henneberg, M., Öhrström, L., Staub, K., & Rühli, F. (2015). Body height of mummified pharaohs supports historical suggestions of sibling marriages. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 157(3), 519-525. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22728

Halawa, A. (2023). Influence of the traditional food culture of ancient egypt on the transition of cuisine and food culture of contemporary egypt. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-023-00177-4

Hawass, Z., Gad, Y., Ismail, S., Khairat, R., Fathalla, D., Hasan, N., … & Pusch, C. (2010). Ancestry and pathology in king tutankhamun's family. Jama, 303(7), 638. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.121

He, X. (2023). On the relationship between maat’s concept and female status in ancient egypt. BCP Education & Psychology, 11, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.54691/2adqmm67

Karenga, M. (2003). Maat, the moral ideal in ancient egypt.. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203502686 Lev, E. and Lev-Yadun, S. (2016). The probable pagan origin of an ancient jewish custom: purification with red heifer’s ashes. Advances in Anthropology, 06(04), 122-126. https://doi.org/10.4236/aa.2016.64011

Kawai, N. (2010). Ay versus horemheb: the political situation in the late eighteenth dynasty revisited. Journal of Egyptian History, 3(2), 261-292. https://doi.org/10.1163/187416610x541727

Khalil, R., Moustafa, A., Moftah, M., & Karim, A. (2017). How knowledge of ancient egyptian women can influence today’s gender role: does history matter in gender psychology?. Frontiers in Psychology, 07. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02053

Marriage in Ancient Egypt. (2024). https://ancient-egypt-online.com/ancient-egypt-marriage.html

Mohammed, G., Hassan, M., & Eyada, M. (2014). Female genital mutilation/cutting: will it continue?. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(11), 2756-2763. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12655

Ndou-Mammbona, A. and Mavhandu-Mudzusi, A. (2022). Could vhavenda initiation schools be a panacea for hiv and aids management in the vhembe district of south africa?. Curationis, 45(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v45i1.2356

Nicholas, C. (1990). The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. Thames and Hudson.

Onstine, S. (2010). Gender and the religion of ancient egypt. Religion Compass, 4(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8171.2009.00178.x

Toonen, W., Graham, A., Pennington, B., Hunter, M., Strutt, K., Barker, D., … & Emery, V. (2017). Holocene fluvial history of the nile's west bank at ancient thebes, luxor, egypt, and its relation with cultural dynamics and basin‐wide hydroclimatic variability. Geoarchaeology, 33(3), 273-290. https://doi.org/10.1002/gea.21631

Walls, N., Woodford, M., & Levy, D. (2014). Religious tradition, religiosity, or everyday theologies? unpacking religion's relationship to support for legalizing same-sex marriage among a college student sample. Review of Religious Research, 56(2), 219-243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-013-0140-3

Zapletniuk, O. (2021). Queen Ankhesenamun and the Crisis of the Amarna Dynasty.. https://doi.org/10.15407/preislamic2021.02.061

الدین, ر. (2022) . الأطعمة الطقسیة والعادات الغذائیة فی المسیحیة القبطیة الأرثوذکسیة : التاریخ والمعنى. المجلة العلمية لکلية السياحة و الفنادق جامعة الأسکندرية, 19(1), 36-50. https://doi.org/10.21608/thalexu.2022.137588.1083

فرج, ف. (2015). المجتمع المصرىالقدیم وفلسفه القانون. حوليات أداب عين شمس, 43(ینایر - مارس (ب)), 389-402. https://doi.org/10.21608/aafu.2015.6342

محمود, م. (2021). عدم المساواة بین الجنسین فى مصر القدیمة. مجلة کلیة السیاحة والفنادق - جامعة مدینة السادات, 5(2), 160-178. https://doi.org/10.21608/mfth.2021.273306

———

Music Used

'Simplicity' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'Meanwhile' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'At The End Of All Things' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'Echoes' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'The Long Dark' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'Moonlight' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

The marriage of King Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun, rooted in love and political strategy, aimed to strengthen the traditional god’s worship following Akhenaten's reign. Their relationship blossomed, if tender artifacts found in Tut’s tomb are to be believed. Their short reign highlighted their partnership's cultural significance in ancient Egypt. Where did it start? Let me tell you a story. Once upon a time…