Take Me to Snurch: Bringers of Divine Serpent Wisdom and Inspiration

Why did it have to be flying snakes? Because they are fascinating. What are the archaeozoological implications of a flying snake? Does it have wings? Does it have legs? Well, sometimes.

Is it an animal or more specifically human? Or a bit of both? Again, one will often find that it depends on the individual myth, even more specifically than the culture and time.

The difference between the looks that various cultures give to serpents. It's a bit of a modern 'f*** you' toward the rest of the world that there is such animosity pointed toward snakes that stems from the Christian mythology/religion. This, if even subconsciously, continues to influence the perception of snakes. But there are so many more examples of strength and wisdom. And sure, snakes are dangerous, they can hurt us, but just like broad bouncers at clubs that also makes them ideal protectors.

To be clear, these are not dragons, I'm not discussing Yuan-ti or all of the varieties of Nāga or all individual names for the lower body of a snake, or the upper body of human individuals from various mythologies. Neither am I talking about the world serpents, cyclical tail-biting serpents, mythical serpent monsters, nor even just mythical or folkloric snake snakes. I've decided to narrow my focus to snakes with feathers or plumage, which includes snakes with wings. While there are many examples representing the formers, from all over the world, I tried to investigate how universal the plumed/feathered serpent idea has been. And, well, it hasn't, not completely. Many snake deities appear all over the world, and many of them are connectors or lords of the underworld, but they aren’t usually depicted with feathers.

Couatl

Figure 1. Couatl from the Dungeons and Dragons Monster Manual

The Couatl, a medium-sized lawful good celestial, are divine caretakers said to be guardians created by a benevolent god at the beginning of time (D&D Monster Manual: 269). This being, along with the majority of Dungeons and Dragons gods and monsters, were and continue to be inspired by the characters of the ancient world.

Starting with the modern take on a snake-like creature may be the first step for many people into mythological figures. While this can be detrimental due to a skewed image of how this being was supposed to be (Tiamat is a good example of this) whoever the writer is for this divine being got a decent amount in line with the consensus of how this deity would act. Of course, in mythology, there is typically only one, not a species, and typically on the stone working and paintings depicting one of the gods of creation, they aren't shown with wings, just feathers. In the image above, from the monster manual, you can see how awesome it looks and artistic license is completely beneficial. I can't and won't speak for the artist, so I just wonder if they also pulled inspiration to add the wings based on the cobra goddess Wadjet when combined with the vulture goddess Nekhbet, the snake with bird wings. Either way, I'm completely pro this Dungeons and Dragons deity-creature that shows these unordinary chimaera creatures in a positive light.

Speaking of the Monster Manual, it’s the fictional medieval bestiary. From real volumes we have most wyvern creatures (a pair of hind legs and wings):

The Amphisbaena

Figure 2. A two-headed lizard or serpent has one head at the front and another at the tail, allowing it to move in any direction. Gaius Julius Solinus and Isidore of Seville observed that when both heads try to lead, it moves in circles, dragging its body. Both heads eat fish and share food with the body. Its eyes shine like lamps, and it withstands cold. It typically appears as a dragon-like creature with wings, two feet, horns, and a second head on its tail. (Aberdeen University Library, Univ. Lib. MS 24 (Aberdeen Bestiary), folio 69v).

The Aspis

Figure 3. The asp is a snake that avoids magic by pressing one ear to the ground and covering the other with its tail. It is often shown with wings. Unusually, a man seems to be hitting the asp with a stick while the asp breathes fire. The man, likely a magician, is typically wearing what’s called a “Jewish hat.” (Aberdeen University Library, Univ. Lib. MS 24 (Aberdeen Bestiary), folio 67v).

The Boa

Figure 4. The boa is an enormous snake found in Italy. It feeds on cattle by it sucking the milk from a cow's udder, sometimes taking so much that the cow dies. (Bodleian Library, MS. Bodley 764, folio 98r).

The Jaculus

Figure 5. The jaculus (or javelin) is a flying snake that waits in trees for an animal to pass, then drops down to catch and kill it (Bodleian Library, MS. Bodley 764, folio 98v).

The Scitalis

Figure 6. The scitalis is a snake with such an appearance that it would stun the viewer. It is usually shown with wings and legs. Bodleian Library, MS. Bodley 764, folio 97r

The Serpens

Figure 7. Snakes crawl using their scales, always twisted and coiled. There are as many snake types as there are poisons. As they age, they lose sight but can regain it by eating fennel. To renew, they fast until their skin loosens, then shed it through a small space. This shedding symbolizes letting go of the old self through the "narrow way to salvation," represented by Christ. A snake spitting venom signifies ridding oneself of evil before church. A snake fleeing from a naked man shows how the devil retreats when one renounces wickedness.

These and other “flying snakes” in medieval bestiaries tend to have legs or are a total chimaera, but if we narrow the field to only wings on a snake:

The Siren

Figure 8. The name "siren" refers to a winged white snake. Isidore of Seville mentions that in Arabia, there are winged snakes called sirens, whose bite causes death before any pain starts. The siren snake signifies those who are conscious of sin and full of remorse when they commit sins, and yet are so miserable and weak that they allow themselves to be overcome by wicked temptation (Thomas of Cantimpré).

Examples from the Olmeca - Juxtlahuaca cave and La Venta Stelae 19

Retracing the myth back to what is understood by historians to be the first example of this god, at least in the Americas is from the Olmeca. Some of the earliest representations of feathered serpents in Mesoamerica appear in the Olmec culture [c. 1500–400 BCE] (Coe, 1968; Diehl, 2004). During the formative period, in caves in the state of Guerrero, Mexico murals linked to the Olmec motifs and iconography were painted (Grove, 2000). This wide-sweeping cultural touchstone extended from the Gulf of Mexico to Nicaragua, likely thanks in part to the expansive trade routes built on high-value materials such as 'greenstone', shell, and obsidian (Hirth et al, 2013). Most surviving representations in Olmec art, such as the painting in the Juxtlahuaca cave (Figure ), show the Feathered Serpent as a crested rattlesnake, sometimes with feathers covering the head, the body, and sometimes including legs, and often close to humans like in Monument 19 at La Venta, c. 1200/1000-400 BCE (Diehl, 2004; Garcia, 2011) (Figure 10). It is believed that entities such as the feathered serpent were the forerunners of many later Mesoamerican deities because the Olmec culture predates the Maya and the Mixtecs (Covarrubias, 1957: 62; Joralemon, 1996: 58) although experts do disagree on the feathered serpent's religious importance to the Olmec due to the lack of lasting documentation like the Popul Vuh, which records the Maya culture (Diehl, 2004: 103–104). H.B. Nicholson notes that as early as the Middle Formative (Preclassic) in the Olmec tradition, images of serpents with avian characteristics were often represented in several types of artefacts and monuments (Nicholson, 2001). This composite creature (a chimaera) has also been called the “Avian Serpent” and “Olmec God VII,” and appears to constitute an earlier form of the later full-fledged Feathered Serpent, the rattlesnake covered with feathers, perhaps with at least some of the same celestial and fertility connotations as in later documented myths (Garcia, 2011; Nicholson, 2001).

Figure 9. A Feathered Serpent from the Juxtlahuaca cave, the red Feathered Serpent has a crown of worn green feathers. Photo by Matt Lachniet, University of Nevada at Las Vegas.

Figure 10. La Venta Stelae 19 (c. 1200/1000-400 BCE), depiction of the Avian Serpent God from the La Venta site in the Olmec Heartland. Photo courtesy George & Audrey DeLange.

*More general information about the Olmecs

Feathered serpent - Teotihuacán

An overlapping and slightly later dating site in South Central Mexico is the gridded city site of Teotihuacán c. 200 BCE-700 CE also features a feathered serpent, shown most prominently on the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, built c. 150-200 CE (Figures 11-16)(Castro, 1993; Taube, 1992; 1995). On the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, the Serpent itself is the prominent form, with the body appearing to be swimming among the shells and on its tail, just before the rattle is wearing masks which have been suggested to represent either: Tlaloc, the human and snake-like god of rain, a "war serpent" as claimed by Mary Ellen Miller and Karl Taube (Miller & Taube,1993:162), or that the mask represents the "fire serpent" wearing a headdress with the Teotihuacán symbol for war, Michael D. Coe claims (Coe, 2002). It is also thought, by some, that in the eyes of these figures, there is a spot for obsidian glass to be put in. This can further connect these serpent depictions to the Olmec culture and trade and their version of the god itself.

Figures 11-16. All photos in this group are courtesy of me, taken at Teotihuacan in the summer of 2014.

*Teotihuacan Research Laboratory: https://teo.asu.edu/about/about

*More about the Feathered Serpent Pyramid

K’uk’ulkan [God H] - Maya

In the region from Chichen Itza down to Guatemalan highlands the Feathered Serpent God got a name. In the Yucatec Mayan tradition the name is K'uk'ulkan, in K'iche' Maya, Q'uq'umatz. No matter the spelling, these different names are believed to represent the same Flying Serpent God and all as part of the same multi-region cult (Braswell, 2013L; Recinos et al., 1954). According to Miller and Taube (1993), K'uk'ulkan was rare in the Classic Maya Civilization, but in the K'iche' Popol Vuh, Q'uq'umatz, the God associated with water, clouds, the wind and the sky, teamed up with Tepeu, God of lightning and fire, who were the duo of Gods that created humanity (Carmack, 2001; Christenson 2003, 2007; McCallister, 2008). While Qʼuqʼumatz may originally have been the same god as Tohil, the Kʼicheʼ sun god who also had attributes of the feathered serpent, they seemed to have diverged later (Fox, 1987; 2008). This also played a role in the ballgame myth with the hero twins and thus has shown up on ballcourts as markers (Figure 17 & 18) (Fox, 1987; 2008). Qʼuqʼumatz's main job is to carry the sun across the sky and down into the underworld and would have acted as a mediator between the various powers in the Maya cosmos (Fox, 1987; 2008; 1991).

Figure 17. Ballcourt marker taken at Yaxchilan (Whitehouse 2013).

Figure 18. Ballcourt marker at Mixco Viejo, depicting Qʼuqʼumatz carrying Tohil (as the sun) across the sky in his jaws. By Simon Burchell, 2005.

A few examples of this diety are also found across the Mayan world. In Yaxchilan, the "Vision Serpent", is shown in detail on Lintel 15 (Figure 19) and is depicted on pillars. Another example is the flying serpent atop the World tree in Palenque as I've discussed in my old Pakal Coffin Lid post. War Serpent or Waxaklahun Ubah Kan was another one of the names for the Classic period version of K'uk'ulkan which extended past the Classic period into the Post-classic and out of the initial Maya area. Another example from after the main part of the Classic Period is from Labna, a palace site built in the Late and Terminal Classic periods has "serpents adorn[ing] the corners of the principal facade. Characteristic of the Vision Serpent, there appears to be either an anthropomorphic deity or the spirit of an ancestor emanating from the gaping jaws of the serpent's mouth" (Ivanoff, 1973). In the post-classic period, the Gods’ following was found in the Guatemalan Highlands (Sharer & Traxler, 2006).

Figure 19. A Vision Serpent, detail of Lintel 15 at the Classical Maya site of Yaxchilan.

On one of the buildings of Uxmal (Yucatec Maya: Óoxmáal) in the nunnery quadrangle, a flying serpent is built into the lattice design (Figure 20). From the Terminal and Post-Classic on, the balance of powers shifted over time and the ruling powers moved north and built Mayapán (Màayapáan in Modern Maya) and Chichen Itza, two more examples of sites in the Late Postclassic that were both built in the state of Yucatán, Mexico (Figures -23).

Figure 20. Snake and traditional Mayan lattice at Uxmal (Leon Petrosyan, 2018).

Figure 21. Light show of the legend with K'uk'ulkan at Uxmal (Whitehouse, 2013).

Figures 22-23. Serpent plaster motif at the beginning and the top of one of the pyramids at Mayapán (Whitehouse 2013).

Figure 24. K'uk'ulkan at the base of the west face of the northern stairway of El Castillo, Chichen Itza (Frank Kovalchek, 2009).

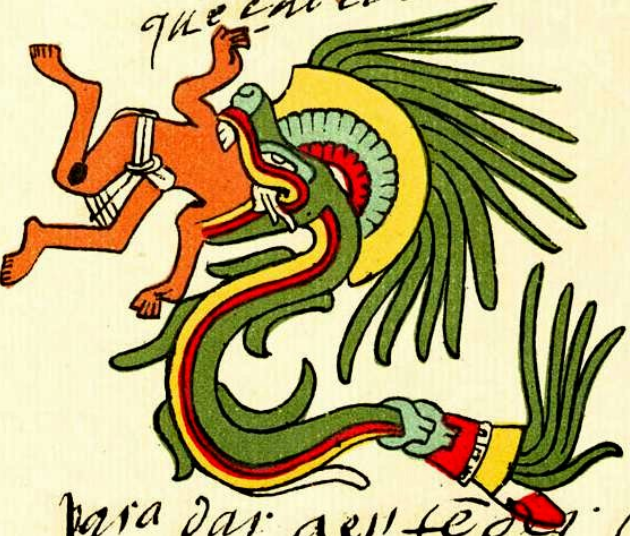

Queztalcoat'l

The name, in parts, means quetzalli - "beautiful" like the quetzal bird and coat'l - "snake or serpent". He was also a human king, and like in the Mayan tradition, he was the God of the wind and sky and was part of the quartet of Gods who created the different versions of the world and brought humanity to what it is now in the time of the 5th sun (Aguilar-Moreno, 2006; Smith, 2003). He stood for or was related to gods of the wind, of the planet Venus, and of the dawn, as well as a patron god of merchants and arts, crafts, learning, and knowledge (Smith, 2003).

Figure 25. Base of staircase at Teotenango, Mexico (Whitehouse 2014).

Figure 26. Quetzalcoat'l in feathered-serpent form as depicted in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, 16th century.

Figure 27. Quetzalcoat'l in human form, using the symbols of Ehecatl, from the Codex Borgia.

Figure 28. Aztec era stone sculptures of feathered serpents on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City (photo by Thelmadatter).

Figure 29. Snake-headed human version (Wonderful Things Art)

Wdjt

The cobra goddess of ancient Egypt, Wadjet or Wadjit, Wedjet, Uadjet or Ua Zit, and wꜢḏyt which means "Green One" in Ancient Egyptian (Budge, 1969). The name has many spellings because of changes in pronunciation over time and location, and many vowels weren't recorded in hieroglyphic texts. In Greece, she was also called Buto, Uto, or Edjo and because of similarities between myths was likely compared with this myth to the Greek story of Leto and Apollo on Delos ("Wadjet|Egyptian goddess" Encyclopedia Britannica). In early periods, before unification, she was a patron goddess of the city of Dep and while she was also a city goddess in Upper Egypt she was the major goddess of all of Lower Egypt (Wilkinson, 2002; 2003). While she's sometimes depicted as a snake-headed woman she is often shown as just a snake (Figures 28). Wadjet was the rearing cobra shown on the crown of the pharaohs (Figure 29).

Upon unification, she became the joint protector of the Pharoah and of all of Egypt along with Nekhbet. Wadjet had a large temple at the ancient Imet (now Tell Nebesha) in the Nile Delta. She was worshipped in the area as the "Lady of Imet" and later she was joined by Min and Horus to form a triad of deities (Razanajao, 2006). In addition to being the protector and guardian of kings, she was also a protector of women in childbirth because in some myths Wadjet was said to be the nurse of the infant god Horus. With the help of his mother Isis, they protected Horus from his evil uncle Set while they taking refuge in the swamps of the Nile Delta ("Wadjet|Egyptian goddess" Encyclopedia Britannica). She was also an extremely powerful goddess whose gaze was said to slaughter enemies.

Figure 33. Vulture goddess

Wadjet and Nekhbet, the vulture-goddess of Upper Egypt, were the protective goddesses of the king and were sometimes represented together on the king’s diadem, symbolizing his reign over all of Egypt. The form of the rearing cobra on a crown is termed the uraeus which was the emblem on the crown of the rulers of Lower Egypt. Nekhbet, also spelt Nekhebit, the vulture, is an early predynastic local goddess in Egyptian mythology, who was the patron of the city of Nekheb (her name means of Nekheb). Ultimately, she became the patron of Upper Egypt and one of the two patron deities for all of Ancient Egypt when it was unified (Wilkinson 2003).

*The Nazit Mons, a mountain on Venus, is named for Nazit, an "Egyptian winged serpent goddess" (USGS 2024, Jobes 1961). Dictionary of mythology, folklore and symbols. Scarecrow Press. According to Elizabeth Goldsmith the Greek name for Nazit was Buto (Goldsmith 1924: 429).

Figure 34. Uraeus with the Red Crown of Lower Egypt. Late Period of Egypt, 664–332 BCE.

Figure 35. Egyptian goddess Wadjet (painting from the tomb of Nefertari, ca 1270 BCE)

Figure 36. A gold amulet of Wadjet (from Tutankhamun's tomb, ca 1320 BC)

Figure 37. Nekhbet with feathers and shen ring and the crown of Upper Egypt.

Figure 38. Mask of Tutankhamun's mummy featuring a uraeus, from the 18th Dynasty. The cobra image of Wadjet with the vulture image of Nekhbet represents the unification of Lower and Upper Egypt.

Figure 39. Four golden uraei cobra figures, bearing sun disks on their heads, on the reverse side of the throne of Pharaoh Tutankhamun (1346–1337 BC). Valley of the Kings, Thebes, New Kingdom (18th Dynasty).

Figure 40. Relief of a Winged Wadjet Eye, Detail of a wall carving in the Tomb of Ramesses, 20th Dynasty, ca. 1186-1155 BC. Valley of the Kings, West Thebes.

Figure 41. Wadjet illustration from Pantheon Egyptien (1823-1825) by Leon Jean Joseph Dubois (1780-1846).

Figure 42. Renenutet sitting on a throne holding a staff, which was used in the ‘opening of the mouth ceremony’ during mummification.

Figure 43. Meretseger, an ancient Egyptian cobra-headed goddess. Based on New Kingdom tomb paintings.

Figure 44. Black granite statue of Meretseger protecting Pharaoh Amenhotep II (1427–1401 BC). From Karnak, Cairo, Egyptian Museum, main floor, room 12.

In the above gallery, I also included images of goddesses with different names and various domains, but are tied together through the complications of history.

Renenutet

She is depicted as a cobra or a woman with the head of a cobra. As a general snake with the feather of Ma'at on her head, she is the goddess of nourishment and the harvest, so many offerings were presented to Renenutet during the annual harvest time (Pinch, 2004). The verbs 'to fondle, to nurse, or rear' can explain the name Renenutet because this goddess was a 'nurse' who cared for the pharaoh from birth to death (Flusser & Amorai-Stark, 1993). She was also the female counterpart of Shai, "destiny", who represented the positive destiny of the child. In Greece, she was the Thermouthis or Hermouthis and embodied the fertility of the fields and was the protector of the royal office and power (Dunand & Zivie-Coche, 2004).

Sometimes, as the goddess of fertility and nourishment, Renenutet and her sometimes husband, Sobek, the crocodile-headed god representing the Nile River, worked together for the annual flooding which deposited the fertile silt that enabled abundant harvests. The temple of Medinet Madi, a small and decorated building in the Faiyum, is dedicated to both Sobek and Renenutet (Dunand & Zivie-Coche, 2004). When Renenutet's husband was Geb she was said to be the mother of Nehebkau, who was occasionally also depicted as a snake, representing the Earth. In later dynastic periods, she was a snake goddess that was worshipped over the whole of Lower Egypt. Over time Renenutet was increasingly associated with Wadjet and eventually, was even identified as an alternate form of Wadjet herself.

Meretseger

Meretseger was the patron of the artisans and workers of the village of Deir el-Medina, who built and decorated the great royal and noble tombs (Spencer, 2007). Desecrations of rich royal burials had already been happening since the Old Kingdom of Egypt (27th/22nd century BC), and sometimes, often by the workers themselves. Therefore, the genesis of Meretseger was to fulfil the need to identify a guardian goddess, as dangerous and merciful of the elite, as are most goddesses (Hart, 1986). Meretseger was sometimes portrayed as a cobra-headed woman, though this iconography is rather rare ("Gods of Ancient Egypt: Meretseger". www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk) and in this case, she could hold the was-sceptre as well as having her head surmounted by the feather of Ma'at and armed with two knives ("Stela Showing Meretseger, Ancient Egypt collection". www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk; Peacock, Lenka. "Goddess Meretseger at Deir el-Medina". www.deirelmedina.com). More commonly, she was depicted as a woman-headed snake or scorpion, (Peacock, Lenka. "Goddess Meretseger at Deir el-Medina". www.deirelmedina.com; "MERT SEGER in "Enciclopedia dell' Arte Antica" ". www.treccani.it) or sometimes a cobra-headed sphinx, lion-headed cobra or a three-headed [woman, snake, and vulture] cobra ("Gods of Ancient Egypt: Meretseger". www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk). On various steles, she wears a modius surmounted by the solar disk and by two feathers, or the hathoric crown (the solar disk when between two bovine horns - Figure 39 above) (Peacock).

https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/renee-whitehouse/episodes/Take-Me-to-Snurch-pt--2-e2ottc5

The Ophis Pterotos

Figure 45. Artistic rendering of the Ophis Pterotos, sold at https://www.velvastein.com/product-page/ophis-pterotos-cropped-tee

The “Winged Serpent” was a breed of feathery-winged snake that guarded the frankincense groves of Arabia. They were sometimes called Ophies Amphipterotoi or "Serpent with Two-Pairs of Wings."

From Greek: Οφις Πτερωτος/ Οφιες Πτερωτοι

To Latin: Singular - Ophis Pterôtos/ Ophies Pterôtoi Plural - Ophis Pterotus/Ophies Pteroti - Winged Serpent(s)

Frankincense and myrrh have long been linked to winged serpents that protect fragrant groves. Herodotus described these trees in Arabia, guarded by such serpents (Al-Mathal, 2007; Freedman, 2005). This connection appears in various classical writings, including Isidore of Seville's notes on pepper harvesting accounts in India (Freedman, 2005). The image of winged snakes and frankincense also appears in Etruscan art, indicating a wide cultural impact (Voisin, 2022). These stories highlight the great value placed on rare spices and scents in ancient times, often suggesting they come from remote and dangerously inaccessible places (Freedman, 2005).

*Today, frankincense and myrrh trees confront threats from habitat loss and overharvesting, emphasizing the need for conservation and their cultural and religious importance could inspire broader efforts to protect biodiversity (Small, 2017).

Herodotus, Histories 2. 75. 1-4 (trans. Godley) (Greek historian C5th B.C.) :

"There is a place in Arabia not far from the town of Bouto (Buto) where I went to learn about the Winged Serpents (ophies pteretoi). When I arrived there, I saw innumerable bones and backbones of serpents: many heaps of backbones, great and small and even smaller. This place, where the backbones lay scattered, is where a narrow mountain pass opens into a great plain, which adjoins the plain of Aigyptos (Egypt).

Winged serpents (ophies pteretoi) are said to fly from Arabia at the beginning of spring, making for Aigyptos; but the ibis birds encounter the invaders in this pass and kill them. The Arabians say that the ibis is greatly honored by the Aigyptoi (Egyptians) for this service, and the Aigyptoi gives the same reason for honoring these birds."

Herodotus, Histories 3. 107. 1 - 110.1 :

"Again, Arabia is the most distant to the south of all inhabited countries: and this is the only country which produces frankincense and myrrh and casia and cinnamon and gum-mastich. All these except myrrh are difficult for the Arabians to get. They gather frankincense by burning that storax which Phoinikes (Phoenicians) carry to Hellas; they burn this and so get the frankincense; for the spice-bearing trees are guarded by small Winged Snakes (ophies hypopteroi) of varied color, many around each tree; these are the snakes that attack Aigyptos (Egypt). Nothing except the smoke of storax will drive them away from the trees . . .

So too if the vipers and the Winged Serpents (ophies hypopteroi) of Arabia were born in the natural manner of serpents life would be impossible for men; but as it is, when they copulate, while the male is in the act of procreation and as soon as he has ejaculated his seed, the female seizes him by the neck, and does not let go until she has bitten through. The male dies in the way described, but the female suffers in return for the male the following punishment: avenging their father, the young while they are still within the womb gnaw at their mother and eat through her bowels thus making their way out. Other snakes, that do not harm men, lay eggs and hatch out a vast number of young. The Arabian Winged Serpents do indeed seem to be numerous, but that is because (although there are vipers in every land) these are all in Arabia and are found nowhere else. The Arabians get frankincense in the foregoing way."

Aelian, On Animals 2. 38 (trans. Scholfield) (Greek natural history C2nd A.D.) :

"The Black Ibis does not permit the Winged Serpents (Ophies Pterotoi) from Arabia to cross into Aigyptos (Egypt), but fights to protect the land it loves."

Aelian, On Animals 16. 41 :

"Megasthenes states that in India there are . . . snakes (ophies) with wings and that their visitations occur not during the daytime but by night, and that they emit urine which at once produces a festering wound on any body on which it may happen to drop."

Nāga

The Nāga are serpentine beings in Hindu and Buddhist traditions, often seen as shape-shifting, multi-headed cobras with divine qualities (Lange, 2019). While typically wing and featherless, they sometimes conflict with the bird-like Garuda (Ryoo, 2023). Nāgas symbolize fertility, prosperity, and healing, especially for women in South India (Allocco, 2013). They are complex figures that can bless or curse, with their worship embedded in local customs (Moonkham, 2021; Allocco, 2013). In ancient epics, they embody authority and may be portrayed as foes, reflecting the fusion of traditions in Hindu mythology (Ryoo 2023). Their myths continue to shape modern South Asian culture, influencing religious practices, temple construction, and perceptions of the surrounding environment (Moonkham 2021, Allocco 2013).

In Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese culture, in Indonesia, a nāga is depicted as a crowned, giant, magical serpent, sometimes depicted as winged (Figure 46). It is derived from the Shiva-Hinduism tradition, merged with Javanese animism. In Indonesia, Nāga are mainly influenced by Indic tradition and combined with the native animism tradition of sacred serpents. In Sanskrit, the term nāga means snake, but in Java, it normally refers to a serpent deity, associated with water and fertility. In Borobudur, the nagas are depicted in their human form, but elsewhere they are depicted in animal shape (Miksic 2012).

Figure 46. Crowned golden nāga-woodcarving at Keraton Yogyakarta, Java. © CEphoto, Uwe Aranas

The Nāga myth is closely linked to traditional buildings and beliefs. In Balinese sacred architecture, serpent figures represent natural elements like earth, water, clouds, and rainbows (Paramadhyaksa, 2016). Sundanese culture, shaped by various philosophies, is seen in the traditional homes of Kampung Naga in West Java (Darmayanti, 2016). These homes reflect cosmological values and are believed to have "soul" and "breath" (Darmayanti, 2018). Stories from the Kampung Naga community involve themes of revelation, reincarnation, and divine origins, which have been studied through Levi-Strauss' linguistic model to uncover Javanese cosmological structures (Iryana, 2014). Preserving these traditional villages and their architecture is crucial for Indonesian cultural tourism, providing a glimpse into ancient traditions and beliefs (Darmayanti, 2018).

Staff Coilers

Hermes’ caduceus is usually represented as two snakes winding up the length of a central staff, often surmounted by wings. According to the mythology, it was created when Hermes threw his staff at two snakes in an attempt to end a fight between them. The snakes stopped their battle and wrapped themselves around the rod. This combination of staff and two snakes became the symbol for resolving disputes peacefully. In time, it also became a mark of commerce. But generally the staff has the wings as the symbol of Hermes, not the snakes (Figure 50-53). Although, there are always exceptions, just not in the originals (Figures 54 & 55).

Ningishzida and Mushussu were significant snake-associated deities in Mesopotamian mythology. Mushussu, however, is another example of a chimera, in the descriptions the only serpent-like feature is the tongue. Mushussu also known as ḪUŠ, which translates to "reddish snake" or "fierce snake" or “Furious-Snake”, was a protective spirit depicted in wooden and clay figures guarding building entrances (Wiggerman, 1992). Some authors even translate it as a "splendour serpent" while being shown as a four-legged dragon-type creature without wings (Black & Green 1992).

Figure 56. The "Libation vase of Gudea" with the dragon Mušḫuššu, dedicated to Ningishzida (21st century BC short chronology). The caduceus (right) is interpreted as depicting god Ningishzida.

Ningishzida

A Sumerian god and city god of Gishbanda, Ningishzida was often depicted as a serpent, but could also be shown as human with bashmu, mushussu, and ushumgal at his side. Ningishzida was also associated with plants and agriculture and was believed to provide grass for domestic animals as his name may mean "Lord Productive Tree". Ningishzida, a major Babylonian god of healing, was symbolized by twin snakes intertwined around a staff on a ceremonial beaker from around 2000 BCE (Johnston, 1986). This representation predates the Greek Aesculapian myth and Biblical references and could have been the earlier incarnation that inspired the Caduceus. These mythological beings were part of a complex pantheon of gods, goddesses, demons, and monsters in Mesopotamian culture (Black & Green 1992). The significance of snake-related iconography extended beyond Mesopotamia, as evidenced by a copper statuette from southeastern Iran dating to the 3rd millennium BCE, which hints at an important, yet unknown, mythological or religious identity (Eskandari et al. 2022). These findings underscore the widespread importance of snake symbolism in ancient Near Eastern religions. Ningishzida's power to shed his skin and rejuvenate was seen as a symbol of curing illness (Johnston, 1986). In the Babylonian pantheon, major gods like Ningishzida often evolved from more local city-state deities, acquiring more defined powers and personalities over time (van Buren, 1934). These protective spirits or divine entities, whether major gods or secondary deities, illustrate the need for divine protection and were common in Mesopotamian culture as guardians against demonic forces (van Buren 1934, Wiggerman 1992).

The Peacock-Plumed Snake of Glamorgan, Wales

British mythology features many amazing creatures, especially dragons and lizard-like monsters. Notably, jewel-scaled, plume-winged dragons were reported in Wales until the 1800s. Marie Trevelyan mentioned them in her 1909 book about Welsh folklore. An elderly man from Penllyne Castle described them as beautiful, coiled when resting, and covered in sparkling jewels. When startled, they quickly hid, but when angry, they flew overhead with bright wings and eyes like peacock feathers. The old man claimed his father and uncle had killed some because they threatened chickens and their extinction was blamed on the danger they posed to farms.

An old woman from Penmark Place in Glamorgan often heard stories of winged serpents. She described a "king and queen" of these serpents near Bewper, where elders said treasure might be buried. Her grandfather encountered one in Porthkerry Park, and after a long watch, he and his brother shot it, injuring her uncle. They eventually killed the serpent, and she recalled its skin and feathers before they were discarded after her grandfather died. The serpent was as well-known as foxes in Penmark. In 1812, similar creatures were reported in northern Wales, with some folklorists suggesting they were pheasants. However, the ring-necked pheasant was too established to be mistaken for a mythical serpent, especially since only males have bright feathers. It's unlikely they were unknown pheasants resembling snakes, as such striking birds would have been preserved in homes and museums, and often featured in countryside magazines. Hunters would recognize them as just birds, not mythic reptiles like Quetzalcoatl.

No bird of prey matches the description of these creatures. While dragon myths often feature buried treasure, Wales's feathered serpents don't align with other British legends. Some winged serpent dragons, called amphipteres, also exist in legend but lack colorful feathers (Shuker 1997).

Amphiptere

Amphiptere (or Amphithere) is a winged serpent from European heraldry. It typically features light-colored feathers, a long serpentine body like a lindworm, bat-like wings, and a greenish tail similar to a wyvern's. Some have fully feathered bodies, spiky tails, bird-like wings, and beak-like snouts. Amphipteres are rare in heraldry but can be seen on the coat of arms of the House of Potier, which shows a purpure bendlet between two amphipteres. They are also used as supporters for the Duke of Tresmes and Duke of Gesvres.

Serpent-Dragons

The snake holds significant symbolism across cultures in East Asia. In Korean and Far Eastern indigenous beliefs, snakes are associated with creation, shamanism, and thunder gods (Soon Cheon Eom, 2024). They symbolize fertility, abundance, and rebirth due to their biological characteristics (Mi Kyoung Jeon, 2022). In Chinese mythology, snakes are prevalent and ambivalent figures representing fear and renewal (D. Chao, 1979). The symbolism of snakes extends to sandplay therapy, which is a non-verbal therapeutic approach in which miniature figures can represent various concepts such as death, rebirth, healing, and eternal life, depending on the individual's context (Frambati et al. 2014, Yeong Mi Yeom, 2021). Because snakes are often associated with wisdom, healing, and cosmic principles across cultures, diverse interpretations of snake symbolism highlight their complex role in human psychology and cultural beliefs (D. Chao, 1979). However, while there are serpent deities that could fly, they do not appear to have feathers and the famous serpentine dragons lack wings as well, with the tuffs on their bodies being furs rather than feathers.

Siberian folklore, particularly among the Khakas and Yakuts, features prominent snake and serpent-dragon imagery. In Khakas culture, the snake was considered sacred and associated with time, calendar rites, fertility, and natural objects like mountains and water (Burnakov, 2020). The syr chylan or 'snake-dragon' that appears in heroic tales lacked the features of European dragons, wings and the ability to breathe fire (Burnakov, 2020). Yakut heroic epics depict serpentomorphic characters as markers of demonic entities and the underworld, often using Mongolian-origin lexemes (Макаров, 2023). These serpent motifs in Siberian folklore share similarities with ophidian cults throughout the Americas, suggesting a possible common origin in northeastern Asia (Mundkur et al., 1976). The snake's image in Khakas folklore underwent significant changes, evolving from a revered patron spirit to a more negatively connoted figure due to historical factors and inter-ethnic interactions (V. A. Burnakov, 2020).

Ancient dragons were often depicted as composite creatures with serpentine forms and avian characteristics, including feathers (Carlson, 1982). These Siberian dragon-serpents share characteristics with similar creatures in broader Eurasian mythology, such as the composite lion-dragon found in Mesopotamian, Canaanite, and East Asian traditions (Lewis, 1996). Common features across these mythologies include associations with water, the underworld, and immense size. The serpent-dragon imagery often symbolizes powerful, sometimes antagonistic forces in these cultural narratives, rather than the protective deities we are focusing on (Burnakov, 2020; Макаров, 2023; Абсалямова et al., 2023; Lewis, 1996).

The Big Snake, The Great Serpent, and The Horned Serpent

Native American symbols, like the Feathered Serpent, have varied meanings across tribes. The Feathered Serpent/ the Great Serpent symbol originated from the ancient Mississippian culture, known for its Mound Builders, who associated deep mystical value with the serpent. The Mississippians' sacred rites and symbols influence many Native American tribes today, including the Creek, Choctaw, Cherokee, Seminole, and Chickasaw. Their sacred ceremonies, stories, and symbols likely come from the Mississippians. The Great Serpent symbol stood for a harmful being, often representing chaos and malevolence, while similar symbols, such as the Horned Serpent and Feathered Serpent, are seen as benign despite their fearsome nature. Abenaki mythology features a great serpent called Kita-skog ("Big Snake"), further emphasizing this duality. Malevolent serpent names include Utkena and Mishipizheu.

Depending on which local Indigenous group one is discussing the winged serpent has multiple motifs, different designs, or is artistically altered. All meaning the same thing, leading to similar, if not overlapping legends about the mythical figure generally shown as a rattlesnake with divine power properties.

Big Snake

In Navaho Windway legend, the Big Snake is a prominent mythological creature often depicted in sandpaintings. These short, thick snakes, sometimes horned and feathered, serve as guardians. Their horns and feathers represent power and speed, while red spots indicate venom and speckled bodies enhance their terror. Big Snakes can appear straight or crooked, symbolizing male and female power dynamics. In Striped Windway paintings, a crooked black Big Snake guards with a frightening presence ("mother snake of black water with reflections of the moon and arrow points or antelope hoof prints" - Newcomb). The storyteller Lefthanded noted its deadly power, causing illness to return to the supernaturals. Big Snakes feature body markings linked to their dens, deer tracks for food, and moon phases. Thirteen types exist in sixty-six paintings, with no specific preference for main figures or guardians. Smaller guard snakes often bear chevrons, commonly oriented toward or away from the head. The Great Snake can transform men into angry snakes, yet may also offer healing, as seen in Wind and Star Chants.

Horned Serpent

A creature that appears in the oral history of many Native American cultures, especially in the Great Lakes and Southeastern Woodlands. The Horned Serpent, associated with water control and leadership, was central to pilgrimages at Paquimé, Chihuahua, during the Medio period (VanPool & VanPool, 2018). The Horned Serpent was usually viewed as a benign or benevolent though fearful creature such as the Avanyu or Awanyu: a Tewa deity, the guardian of water. Represented as a horned or plumed serpent with curves suggestive of flowing water or the zig-zag of lightning, Awanyu appears on the walls of caves located high above canyon rivers in New Mexico and Arizona and so guards waterways and is a harbinger of storms as well as being a protector of the Pueblo people ("Avanyu Trail day" Museum of Indian Arts & Culture). The earliest representations of Avanyu may be from 1000 CE and were found on Mimbres pottery, which is a precursor to Pueblo pottery. In the Mogollon and Casa Grande districts images of Avanyu appear between 1200 and 1450 CE. Avanyu appears in Tewa and Tiwa-speaking peopled areas around 1350 CE (Diaz 2014).

Figure 67. Rock art at Tsirege depicting Awanyu, a horned water serpent deity. This photo was published in LA-UR-04-8964-CRMP and appeared in Figure 15.13, page 86 (The original uploader was Chyeburashka).

Archaeologist Dr. Polly Schaafsma, whose research specializes in Avanyu mythology among other subjects, writes, “The horned serpent continues to be revered as an important deity among the Pueblos and is known by various names among the different linguistic groups, including Kolowisi (Zuni), Paalölöqangw (Hopi), and Awanyu (Tewa)." Paalölöqangw has control over with the underworld, water sources, and the fertilization of seeds (Lucero 2022). He is sometimes considered a kachina, which is the masked spirit of nature, or the spirit of the ancestors of the Hopi, Zuni and other Pueblo peoples. The Kachina is asked to act as a mediator between the gods and the people and causes rain to fall on the earth (Wright & Bahnimptewa 1973). The horned Kolowisi was praised in Zuni mythology for saving the Zuni people from a great flood (Mills & Ferguson 2008).

Figure 69. The Paaloloqangw Ceremonial at Hopi by Raymond Naha

Figure 70. The Water Serpent Palölökong Kachina (carved by Neil David Sr. 1979)

Figure 71. Zuni water serpent- Kolowisi from the Bureau of American Ethnology (1904).

The Great Serpent

As a common creature in Moundville art, this winged serpent is believed to be the Upper World version of the Great Horned Serpent. The winged serpent is a notable image from the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. It appears in various forms, but the U-shaped serpent with horns and wings was especially significant at Moundville. The winged serpent is the most common design with thirty-three examples, closely followed by the hand-and-eye design with thirty-one examples and similar designs are found in ceramics from the Central Mississippi Valley near Memphis (Steponaitis 1983, Childs 1991; David Dye, personal communication, 1996). The winged serpent is a significant mythological figure in the Eastern Woodlands' religious view, with the wings indicating its celestial location rather than being essential to its form.

Figure 72. This vessel features a winged serpent with deer antlers, forked tongue, and forked eye surrounds. Wings project out of the back of the snake. Moundville Archaeological Park and Museum

Figure 73. The Rattlesnake Disk. A ceremonial stone palette plowed up by a 19th century farmer in Moundville, Hale County, Alabama, United States. Housed in the Jones Archaeological Museum at the Moundville Archaeological Park.

The ancient Winged Serpent symbol originates from the Mississippian culture (1000-1550 CE), the last mound-building culture in the Midwest, East, and Southeast U.S. This culture featured various emblems and motifs and the Great Serpent symbol offers a rich history and inspiration for body painting, tattooing, and piercing. These artworks would showcase cosmic imagery of animals, humans, and mythical creatures for Mississippian Indigenous Americans (Alchin 2012).

Figure 74. The Great Serpent Mound of Southwest Ohio (Photo from the Amusing Planet).

In other cultures, however, the Great Serpent lived in the Underworld, constantly clashing with the Upper World's Thunderers, represented by Birdmen or Falcon beings. Spiral symbols reflect the coiled serpent, symbolizing the mystery of the serpent and its mythological role in the Underworld, death, and as a messenger to the dead.

The Mythology and Meaning of the Great Serpent Symbol

The horned snake is highly significant in Native American myths, especially for the Hopi and Navajo. Insects and animals, including snakes, have important roles in these cultural stories, from minor to major cosmic significance (Cherry, 1993).

The Hopi, a generally small (now) but culturally rich tribe in northeastern Arizona, are known for their snake dance ritual, which has attracted considerable attention from outsiders (Hoover, 1930). This ancient ceremony, possibly dating back to the 14th century, is part of a cycle of ritual dramas aimed at controlling weather, fertility, and health (Udall, 1992). The mythology behind this ritual is, in the world's beginning, winged serpents ruled, symbolized by great serpent imagery. The serpent, representing life, connects with the sun and endures even when harmed even though it might be cut into a dozen parts. The Hopi view the serpent as a messenger to the Earth Spirit. Therefore, at the time of their annual snake dance, they send their prayers to the Earth Spirit by sanctifying a large number of snakes and then freeing them to return to the Earth with the prayers of the tribe.

In Navajo culture, snakes are believed to communicate with the supernatural, contrasting with the bluebird's symbolism of creativity and creation (Golden, 2020).

Soft Conclusions

Some Meanings

These can also sometimes go for other mythical snakes and snake-like creatures in general.

wisdom

fertility - The importance of the Earth to remain fertile.

protector

guidance

a bridge between our world and the afterlife (Ra's journey each night - more just snakes)

danger

What has been discussed are a few examples of the magical flying serpent deities from ancient mythologies up to modern-day folklore, and pop. culture. This is by no means a comprehensive study and is only based on my own limited experience and research into the aspects of the inspiration behind the tattoo I finally got after almost a decade of planning. There are many other examples of wisdom bringing serpents from around the world. Some have been/are directly connected to or are venerated for endowing knowledge or wisdom to humans and are seen as having either an ultimately 'good' or 'evil' motivation. Some are deities or representatives of those deities who rule over those particular aspects. But, for whatever flexible reason, as cultures reach even similar ideas from completely different starting points, serpents seem to have a valuable place in human culture.

Wisdom is constant growth by looking outside oneself and asking, how can I improve? It's an ongoing battle between multiple worlds of competing advice that can only be answered by understanding and a realization that there is more to learn. Listening to and discussing topics and being open to change and different ideas and values (that do not need to be followed) can lead to new ideas and adventures never had. In spiritual contexts, we can acknowledge a belief that this balance is a gift between our lives here on Earth and some divine imagination of the heavens, a gift from any specific deity who saw humans as having great potential**. Wisdom is working with cognisant thoughts, which can give us hope or anxiety on any given day, letting us reason that just because a tomato is a fruit doesn't mean it [necessarily] belongs in a smoothie (even though vegetables are regularly added and taste delicious). As these two worlds are brought together through reasoning out the world around us with wisdom it's logical that most, if not all, cultures create such deities to be connected to the heavens and Earth, and be willing and even wanting to share their wisdom with others.

These are the ideals that I want to remind myself of every day. So I permanently put it on my arm. Many more deities and representations take on a serpentine form and follow different paths in their divinity. This post was about those who inspired me.

In adding to this article, I learned so much more about the fascinating differences that exist between various cultures around the globe. That’s what truly makes the world a beautiful place to inhabit; while symbols may appear the same on the surface, they can carry vastly different meanings and interpretations across different societies and traditions. We can continue to tell our unique and captivating stories to provide valuable new knowledge and insights into the world around us.

Figure 77. My fresh tattoo.

Further Reading

Astrov, M. (1962). The Winged Serpent: American Indian Prose and Poetry.[1946] New York.

Garma, A. (1954). The Indoamerican Winged or Feathered Serpent, the Step Coil and the Greek Meander. American Imago; a Psychoanalytic Journal for the Arts and Sciences, 11(2), 113. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/indoamerican-winged-feathered-serpent-step-coil/docview/1289640998/se-2.

Bibliography

Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel (2006). Handbook to Life in the Aztec World. Los Angeles: California State University.

Alchin, L. (2012). https://www.warpaths2peacepipes.com/native-american-symbols/great-serpent-symbol.htm. Siteseen Limited.

Allocco, A. L. (2013). Fear, reverence and ambivalence: Divine snakes in contemporary south India. Religions of South Asia, 7(1-3), 230-248.

Al-Mathal, E.M. (2007). Commiphora molmol in human welfare (review article). Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology, 37 2, 449-68.

"Avanyu Trail day". Museum of Indian Arts & Culture. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

Абсалямова, Р. А., Войтик, Н. В., & Полетаева, О. Б. (2023). Аксиология глобализации: Лидер–эмпатия–диалог. Век глобализации, (2 (46)), 21-30.

Black, J., & Green, A. (1992). Gods, demons and symbols. Ancient Mesopotamia,(London, 1998), 108-109.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2011, November 2). Wadjet. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Wadjet.

Budge, E. A. Wallis (1969). The Gods of The Egyptians. or Studies in Egyptian Mythology, 2.

Burnakov, V.A. (2020). The Snake and the Serpent Dragon in the Religious and Mythological Representations and Folklore of the Khakas (Late 19th - Mid-20th Centuries).

Carlson, J. B. (1982). The Double‐Headed Dragon and the Sky A Pervasive Cosmological Symbol. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 385(1), 135-163.

Castro, Ruben Cabrera (1993) "Human Sacrifice at the Temple of the Feathered Serpent: Recent Discoveries at Teotihuacan" Kathleen Berrin, Esther Pasztory, eds., Teotihuacan, Art from the City of the Gods, Thames and Hudson, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Chao, D. (1979). The snake in Chinese belief. Folklore, 90(2), 193-203.

Cherry, R. H. (1993). Insects in the mythology of Native Americans. American Entomologist, 39(1), 16-22.

Cierra Tolentino, "Snake Gods and Goddesses: 19 Serpent Deities from Around the World", History Cooperative, January 16, 2022, https://historycooperative.org/snake-gods-and-goddesses/. Accessed September 2, 2024

Coe, Michael D. (1968) America's First Civilization, American Heritage Publishing, New York.

(2002); Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs London: Thames and Hudson.

(2005); "Image of an Olmec ruler at Juxtlahuaca, Mexico", Antiquity Vol 79 No 305, September 2005.

Covarrubias, Miguel (1957). Indian Art of Mexico and Central America (Color plates and line drawings by the author ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 171974.

Darmayanti, T. E. (2016). The ancestral heritage: Sundanese traditional houses of Kampung Naga, West Java, Indonesia. In MATEC Web of Conferences (Vol. 66, p. 00108). EDP Sciences.

(2018). Sundanese traditional houses in Kampung Naga, West Java as part of Indonesian cultural tourism. Journal of Tourism, 3(8), 57-65.

Diaz, RoseMary (14 May 2014). "Avanyu: Spirit of water in Pueblo life and art". Santa Fe New Mexican

Diehl, Richard A. (2004) The Olmecs: America's First Civilization, Thames & Hudson, London.

Dunand, F., & Zivie-Coche, C. (2004). Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE. Cornell University Press.

Eom, S.C. (2024). The Review of Snake and Dragon Worship among Indigenous Tribes of the Far East. Institute for Russian and Altaic Studies Chungbuk University.

Eskandari, N., Shafiee, M., Mesgar, A. A., Zorzi, F., & Vidale, M. (2022). A Copper Statuette from South-Eastern Iran (3rd Millennium BC). Iran and the Caucasus, 26(1), 17-31.

Flusser, D., & Amorai-Stark, S. (1993). The Goddess Thermuthis, Moses, and Artapanus. Jewish Studies Quarterly, 1(3), 217-233.

Fox, John W. (2008) [1987]. Maya Postclassic state formation. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press.

(1991). "The Lords of Light Versus the Lords of Dark: The Postclassic Highland Maya Ballgame". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 213–238.

Fox-Davies, Charles (October 4, 2019). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. London: T.C. & E.C. Jack.

Frambati, L., Pluchart, K., Weber, K., & Canuto, A. (2014). When hands are speaking: sandplay therapy. Revue Medicale Suisse, 10(417), 385-388.

Freedman, P. (2005). Spices and Late-Medieval European Ideas of Scarcity and Value. Speculum, 80, 1209 - 1227.

Garcia, S. A. (2011). Early representations of Mesoamerica’s feathered serpent: Power, identity, and the spread of a cult (Master’s thesis). Ann Arbor: ProQuest.

Golden, R. (2020). Guardian of the Garden.

Goldsmith, Elizabeth Edwards (1924). Life Symbols as Related to Sex Symbolism. Putnam. p. 429.

Grove, David C. (2000) "Caves of Guerrero (Guerrero, Mexico)", in Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: an Encyclopedia, ed. Evans, Susan; Routledge.

Guynes-Vishniac, S. (2022). Feathered Serpent, Dark Heart of Sky: Myths of Mexico by David Bowles (review). World Literature Today, 92, 89 - 89.

Hart, G. (1986). A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses.

Hirth, K., Cyphers, A., Cobean, R., De León, J., & Glascock, M. D. (2013). Early Olmec obsidian trade and economic organization at San Lorenzo. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40(6), 2784-2798.

Hoover, J.W. (1930). Tusayan: The Hopi Indian Country of Arizona. Geographical Review, 20, 425.

Iryana, W. (2014). The Mythology of Kampung Naga Community. AL-ALBAB: Borneo Journal of Religious Studies, 3(2).

Ivanoff, Pierre (1973). Monuments of Civilization: Maya. New York: Brosset & Dunlap.

Johnston, L. (1986). Yet more, yet older snakes. JAMA, 255 18, 2445-6 .

Joralemon, Peter David (1996). "In Search of the Olmec Cosmos: Reconstructing the World View of Mexico's First Civilization", in Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico, eds. E. P. Benson and B. de la Fuente, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., ISBN 0-89468-250-4, pp. 51–60.

Lange, G. (2019). Cobra deities and divine cobras: The ambiguous animality of Nāgas. Religions, 10(8), 454.

Lankford, G. E. (2006). The great serpent in eastern North America. In Ancient objects and sacred realms: Interpretations of Mississippian iconography (pp. 107-135). University of Texas Press.

Lewis, T. J. (1996). CT 13.33-34 and Ezekiel 32: Lion-dragon myths. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 28-47.

Lucero, M. (2022). Finding the Meaning in Ceramic Patterns from a Chaco Canyon Burial.

Макаров, С. (2023). Serpents and serpent-like images in the Yakut heroic epic: Towards a comparative study of demonology of the Turkic-Mongolian peoples. Эпосоведение.

Miksic, J. (2012). Borobudur: Golden tales of the Buddhas. Tuttle Publishing.

Miller, M. E., & Taube, K. A. (1993). The gods and symbols of ancient Mexico and the Maya: an illustrated dictionary of Mesoamerican religion. Thames & Hudson.

Mills, B. J., & Ferguson, T. J. (2008). Animate objects: Shell trumpets and ritual networks in the Greater Southwest. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 15, 338-361.

Min, J., & Jeon, H. (2022). The Possibility of Archetypal Cogitation and Succession Education in East-West Mythological Texts. 동서비교문학저널, (62), 7-44.

Moonkham, P. (2021). Ethnohistorical archaeology and the mythscape of the Naga in the Chiang Saen Basin, Thailand. TRaNS: Trans-regional and-national studies of southeast Asia, 9(2), 185-202.

Mundkur, B.D., Bolton, R., Borden, C.E., Hultkrantz, Ā., Kaneko, E., Kelley, D.H., Kornfield, W.J., Kubler, G.A., Mcgee, H.F., Onuki, Y., Schubert, M.H., & Er-wei, J.T. (1976). The Cult of the Serpent in the Americas: Its Asian Background [and Comments and Reply]. Current Anthropology, 17, 429 - 455.

Nicholson, H. B. (2001). "Feathered Serpent." In David Carrasco (ed).The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures.: Oxford University Press.

Paramadhyaksa, I. N. W. (2009). Makna-makna Figur Naga dalam Seni Arsitektur Bangunan Suci Tradisional Bali. Dewa Ruci: Jurnal Pengkajian dan Penciptaan Seni, 6(1).

Peacock, Lenka. "Goddess Meretseger at Deir el-Medina". www.deirelmedina.com.

Pinch, G. (2004). Egyptian mythology: A guide to the gods, goddesses, and traditions of ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, USA.

Razanajao, V. (2006). D'Imet à Tell Farâoun: recherches sur la géographie, les cultes et l'histoire d'une localité de Basse-Égypte orientale (Doctoral dissertation, Montpellier 3).

Recinos, Adrian; Goetz, Delia; Morley, Sylvanus Griswold (1954). "Popul Vuh, the Book of the People". Los Angeles, USA: Plantin Press.

Reichard, G. A. (2014). Navaho religion: a study of symbolism (Vol. 182). Princeton University Press.

Richard, H. W. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt.

Ryoo, H.J. (2023). A Note on the Role of Nāgas in Ancient Indian Epic: especially in the two stories of the Ādi-parvan of the Mahābhārata. Korean Institute for Buddhist Studies.

Small, E. (2017). 55. Frankincense and Myrrh – imperilled divine symbols of religion’s duty to conserve biodiversity. Biodiversity, 18, 219 - 234.

Smith, Michael E. (2003). The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Spencer, A. J. (Ed.). (2007). The British Museum Book of Ancient Egypt. British Museum.

Taube, K. A. (1992). The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the cult of sacred war at Teotihuacan. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 21(1), 53-87.

(1995). The Rainmakers: the Olmec and their contribution to Mesoamerican belief and ritual. The Olmec World: ritual and rulership, 83-103.

Troshikhina, E. (2013). Sandplay therapy for the healing of trauma. In Is this a Culture of Trauma? An Interdisciplinary Perspective (pp. 227-233). Brill.

Udall, S. R. (1992). The irresistible other: Hopi ritual drama and Euro-American audiences. TDR (1988-), 36(2), 23-43.

USGS (n.d.). Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature: “VENUS - Nazit Mons”.

Van Buren, E. D. (1934). The God Ningizzida1. Iraq, 1(1), 60-89.

VanPool, T.L., & Vanpool, C.S. (2018). Visiting the horned serpent’s home: A relational analysis of Paquimé as a pilgrimage site in the North American Southwest. Journal of Social Archaeology, 18, 306 - 324.

Voisin, C. (2022). Frankincense Fragrances and Winged Serpents in Etruria: Notes on a Tarquinian Sarcophagus. Etruscan and Italic Studies, 0.

Wiggermann, F. A. M. (1992). Mesopotamian protective spirits: the ritual texts (Vol. 1). Brill.

Wilkinson, T. A. (2002). Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge.

Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 213–214

Wright, B., & Bahnimptewa, C. (1973). Kachinas: A Hopi artist's documentary.

------------------

**Stargate SG-1 throwback

![Figure 51. Hermes Ingenui[a] carrying a winged caduceus upright in his left hand. A Roman copy after a Greek original of the 5th century BCE (Museo Pio-Clementino, Rome) Marie-Lan Nguyen (2009)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6598c864ea0f89700c0e4e59/1727411031588-HY6OLBF6RC21AUI7MH3P/Hermes_Ingenui_Pio-Clementino_Inv544.jpg)