Welcome to Jurassic Art

I grew up with the film adaptation of Michael Crichton's story. John Hammond's signature "spared no expense" quote. Dr Alan Grant's claw, Dr Ellie Sattler's dino-dropping search, their two faces beautifully gawking at the Brachiosauruses, and Dr Ian Malcom saying "Life, uh, finds a way". Significantly, people in my parents, mine, and the latest two generations of today wouldn't know about or, most likely, be nearly as interested in dinosaurs or other prehistoric animals without the decades of dedication from scientists and paleoartists. Generally, only the bones of these creatures remain, but because of paleoartists' work in books and museums, most people have an accurate impression of what these creatures looked like. Many paleoartists, including Georges Cuvier, Gideon Mantell, John Martin, Henry Ward, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, Charles R. Knight, and dozens more have worked and continue to work hard to bring the visuals of the ancient world to the present.

As it sounds, the word "paleoart" is a portmanteau of paleo-, meaning ancient (from 'palaeontology' - the study of ancient life), and art. This word was notably coined by Mark Hallett in 1987 and showed up in his published work "The Scientific Approach of the Art of Bringing Dinosaurs Back to Life" from Dinosaurs Past and Present (vol 1) in 1987. Hallett stressed the importance of the cooperative effort between artists, palaeontologists and other specialists in gaining access to information for generating accurate, realistic restorations of extinct animals and their environments. Paleoart is of course not only about dinosaurs, there's art depicting every time from the Hadean (the origin of Earth, though there isn't biology yet) to the Phanerozoic (our current Eon). The biological aspects generally range from the Cambrian Period to the current Quaternary Period, specifically ending around the Pleistocene Epoch with Ice Age animals.

Figure 1. Volcanoes and erosion sculpted Earth 3.5 billion years ago. For nearly 75% of Earth’s history, life consisted of single-celled microbes without a nucleus (prokaryotes). (The Archean World / Peter Sawyer).

Figure 2. Quaternary Period Landscape art print by Publiphoto (Science Source Prints Art Collections)

Palaeoart, the visual representation of prehistoric life, has evolved significantly since its inception in the 15th-16th centuries (Manucci & Romano 2022). Initially, scientists and artists were often the same people, but the field later saw the emergence of specialized paleoartists (Manucci & Romano 2022). Marine mammals, particularly whales, were among the first subjects of palaeoart in the 17th century (Berta 2021).

Paleoart emerged as a distinct genre of art with an unambiguous scientific basis around the beginning of the 19th century, dovetailing with the emergence of palaeontology as a distinct scientific discipline. These early paleoartists restored fossil material, musculature, life appearance, and habitat of prehistoric animals based on the limited scientific understanding of the day. Paintings and sculptures from the mid-1800s such as the landmark Crystal Palace Dinosaur sculptures displayed in London propelled paleontology into the public eye. Paleoart developed in scope and accuracy alongside palaeontology, with "classic" paleoart coming on the heels of the rapid increase in dinosaur discoveries resulting from the opening of the American frontier in the nineteenth century. Visionaries such as Charles R. Knight brought dinosaurs to life with dynamic depictions in the early 1900s.

Since paleontological knowledge and public perception of the field have changed dramatically since the earliest attempts at reconstructing prehistory, paleoart as a discipline has consequently changed over time as well. This has led to difficulties in creating a shared definition of the term. In the ongoing pursuit of scientific accuracy, the distinction between true paleoart and "paleoimagery" has become a focal point within the discipline. Some scholars emphasize the necessity of delineating these terms, with paleoimagery encompassing a wider array of visuals influenced by paleontological concepts but not necessarily bound by scientific precision. As highlighted by Ansón, Fernández, and Ramos (2015:29), this differentiation is crucial.

A proposed definition designates paleoartists as individuals who engage in crafting original skeletal reconstructions or restorations of prehistoric creatures using accepted methodologies. This definition, as articulated by Debus and Debus (2012), aims to clarify the roles and responsibilities of paleoartists in ensuring accuracy in their representations of ancient life forms.

Moreover, it is acknowledged that a comprehensive understanding of paleoart necessitates an element of subjectivity. Each artist brings forth unique styles, preferences, and interpretations that inevitably influence their artistic choices, alongside the overarching objective of maintaining scientific fidelity. The interplay between these subjective elements and the pursuit of accuracy underscores the nuanced nature of paleoart as a creative and scientific endeavour (Witton 2016: 7–8). The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology has defined paleoart as, "the scientific or naturalistic rendering of paleontological subject matter pertaining to vertebrate fossils", a definition considered unacceptable by some for its exclusion of non-vertebrate subject matter (Ansón, Fernándezm & Ramos 2015: 28–34). In paleoart, there are three essential elements defined by paleoartist Mark Witton. These elements are crucial for creating accurate representations of prehistoric life:

Bound by scientific data: Paleoart must be based on scientific evidence and data related to the organisms being depicted. It is important to ensure that the artwork aligns with what is known through research and study.

Involving biologically informed restoration: When there are gaps in the data, paleoartists use biological knowledge to make informed restorations. This process helps fill in missing information and creates a more complete depiction of extinct organisms.

Relating to extinct organisms: Paleoart specifically focuses on portraying organisms that are no longer present today. It captures these creatures in their prehistoric environments, bringing them back to life through art.

By following these guidelines, paleoartists can create engaging and scientifically accurate depictions of ancient life forms, bridging the gap between the past and the present. As the 20th century progressed, paleoart evolved to portray vibrant ecosystems and landscapes. (Berta 2021). The transformative "Dinosaur Renaissance" spanning the 1960s to the 1980s revitalized dinosaur art, leaving an indelible mark on the history of paleoart by also establishing the foundations for palaeoart historiography (Monnin, 2023). This period emphasized the integration of artistic processes in palaeontology and sparked discussions about the field's historical legacy (Monnin, 2023). Today, paleoart continues to be a vital tool in conveying scientific knowledge through engaging museum exhibitions and educational displays (Hillesheim & Palace Dinosaurs, 2022).

Figure 3. Duria Antiquior: A More Ancient Dorset by geologist Henry De la Beche in 1930 - Based on fossils found by Mary Anning, and was the first pictorial representation of a scene from deep time, based on fossil evidence.

Figure 4. Cover art of Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World Hardcover (Edited by Elizabeth Morrison 2019).

As discussed in The Palaeoartist's Handbook by Witton and Paleoart: Visions of the prehistoric past by Lescaze, the practice of paleoart as a "visual tradition" originated in 1800s England (Lescaze 2017; Witton 2018). However, what is extremely interesting to look at are the pieces of 'proto-paleoart' which can be dated back to 500 BCE, even though the scientifically based fossil work in this early period is less concrete. This practice later reached a wonderful number of people in the Middle Ages/Medieval Period because of the volumes of compendiums on the subject of incredible and mythical animals, the bestiarum vocabulum or bestiaries.

The only way we have a world in which Jurassic Park exists is because of palaeontologists, paleoartists, the authors and artists of bestiaries, and hundreds of years of scientific study into the fascinating world of fossils and biology inspired by the crazy creatures found in bestiaries.

Fossil hunting of Today

We seem to be having a new fossil gold age today, finding new species and making new connections to what prehistoric animals looked like and how they may have lived.

With the hard work of scientists around the world, we now have evidence of a giant swimming Spinosaurus, feathered theropod dinosaurs, the skin of non-feathered dinos, a baby dino preserved with soft tissue in amber, and even how pre-dinosaur animals' blood worked. A lot of these articles are very new and some present ideas that are being argued over, but that's good. A healthy discourse and exchanging of ideas introduces more in-depth knowledge and thus, changes ideas of the earth's past and how we got where we are now.

Before we got where we are now, we had an era that is regarded as a palaeontology renaissance (70-90s) when humans finally appreciated that dinosaurs were living, alert, warm-blooded animals that evolved into birds, instead of slow, lumbering, Hollywood-style monsters that just died out due to laziness. Some of the species of animals that were found during this time were the dinosaurs Dilophosaurus (Figures 5 & 6), the theropod dinosaur that spits acid in the movies and the Deinonychus (though technically first described in the 1960s) (Figure ), which the Velociraptors in the Jurassic Park (Figures & ) movie and book were based on. While we have moved past these ideas and visualizations now, worldwide work in continent-wide Africa, China, Mongolia, Myanmar, Pakistan, the Americas, etc. shaped how we look at proto-Triassic animals, dinosaurs and their contemporaries, all animals otherwise, phylogenetic trees, and evolution itself. Moving our planetary understanding of the past forward into connecting with the living creatures that evolved from them.

Figure 7. Size of Deinonychus (6) compared with other dromaeosaurids by Fred Wierum 2017.

While found around a century before the Dinosaur Renaissance, the well-known Archaeopteryx fossil skeleton was found in Southern Germany, an area that was once an archipelago of islands in a shallow tropical sea in the Late Jurassic Period. While agreed that this is a transitional fossil, what should be more appreciated is the feathers alone, and how well the stone was preserved initially and protected by the scientists through time. Many times in history finds such as this were never shown, or even worse, destroyed, because they were controversial. We were, therefore, very lucky with this find.

This links to the knowledge of old creatures. Dragons, unicorns, the Kraken, leviathans, chimaera, etc. were in the world; dangerous and/or magnanimous beings created by the gods or God to keep the old world interesting, as they were believed to be completely real.

Biological connections

What is evident in much of the new research is how much it is obvious that these creatures from the prehistoric world are connected to living animals. According to Witton, there are recommended scientific guidelines that must be followed to be able to classify a piece of art in this genre (Witton 2018: 38). These requirements include the creatures geochronology (its place in time), paleobiogeography (location in the ancient past), a skeletal/body shape reference, and, if possible, an understanding of the organisms' ontogeny, functional morphology, and phylogeny (Witton 2018: 37-43).

I would never argue that geese or swans aren't vicious they seem to be connecting with their distant ancestors and their current relatives in Australia, like the cassowary. As an example of how this species can act, the female half of the mating pair that the Featherdale Wildlife Park had in captivity in 2010 (when I was visiting) was so violent towards the male that they had to keep them separate while not in heat, otherwise the larger female cassowary would attack the male to keep him out of her territory. This isn't only a practice found in birds either; female jaguars in Meso- and South America keep watch over around 9 to 15 sq miles with male territory areas overlapping with various territories of local females (Schaller 1980).

These aren't monsters or skeletons or rocks, they were living animals, as shown in the Paleoart below.

Figure 11. 'Leaping Laelaps' by Charles R. Knight, 1896

Figure 12. Reconstruction in a quadrupedal gait of the skeleton of the Upper Cretaceous of Kundur (Russia) hadrosaurid dinosaur Olorotitan arharensis by Andrey Atuchin (Godefroit, Bolotsky, and Alifanov, 2003).

Jean Hermann's 1800 restoration of the pterosaur Pterodactylus antiquus (Figures 11 & 12)(Taquet & Padian, 2004).

Figure 15. On the left is the standard 5.8 m tall male Masai giraffe, followed by a human in the center left, Arambourigania in the center right, and Captain SuperChunk (as the paper called it) on the right. Hatzegopteryx, as reconstructed here, is not as tall as Arambourgiania, but its larger head and neck probably made it quite the fearsome predator. (Witton 2017).

Figure 16. Pair of azhdarchid pterosaurs: Arambourgiania the Late Cretaceous Maastrichtian species Arambourgiania philadelphiae (Witton 2017).

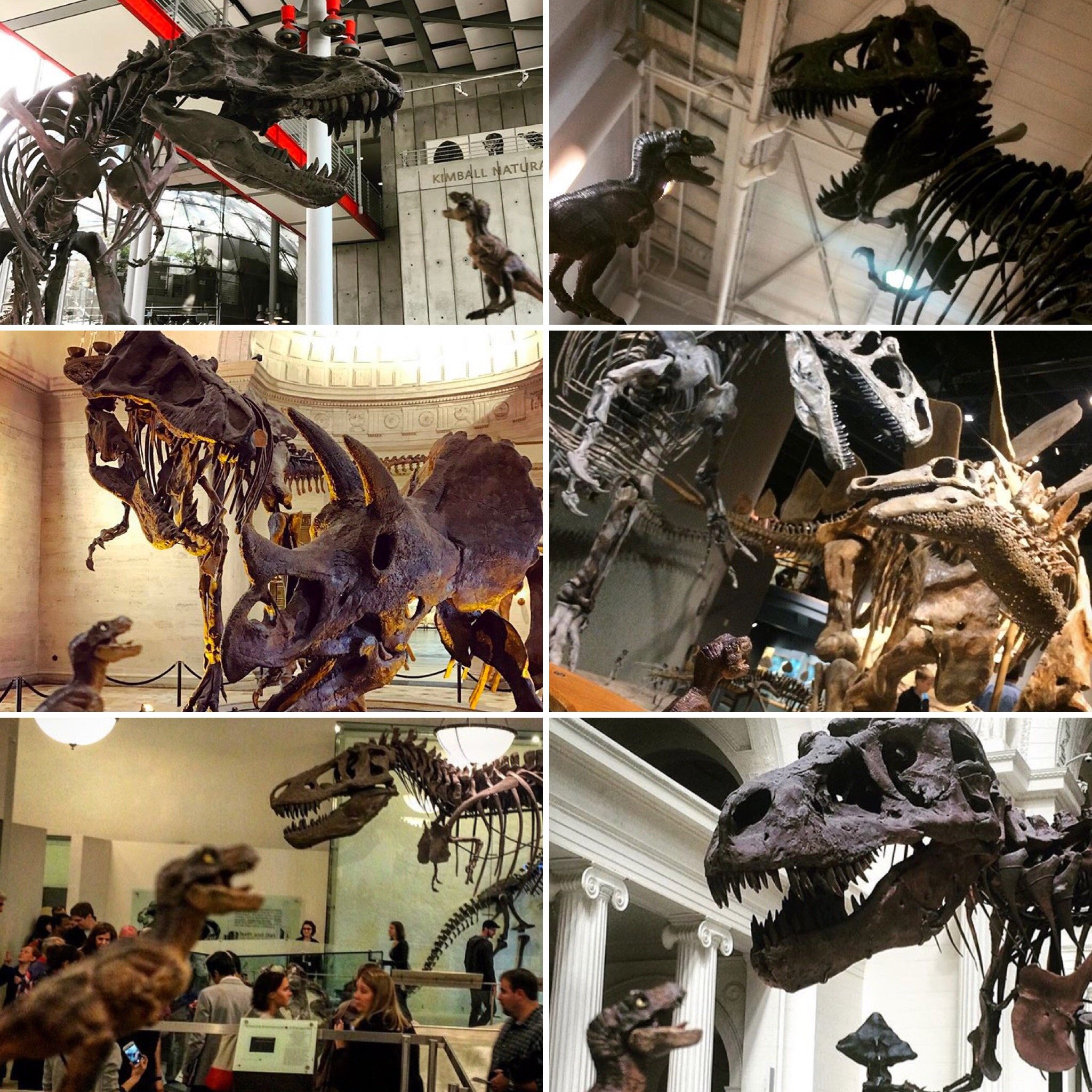

And you don't just have illustrations, the world won't forget the sculptures at the Crystal Palace or all the articulated casts at almost every natural history museum.

Figure 17. Cast of Tyrannosaurus rex specimen AMNH 5027 mounted in a "leaping posture" by Robert Bakker at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science (photo by Scott Robert Anselmo, 2016).

Figure 18. “Carnivorous dinosaurs are great at smiling for photos.” From DISPLAYING YOUR DINOSAUR: FOSSILS VS. CASTS by #MUSEUMPALOOZA.

The transition from the more reptilian depictions of dinosaurs to the updated taxonomy models marked a significant evolution in paleoart. The Crystal Palace models, despite their inaccuracies by modern standards, played a crucial role in advancing paleoart as both a serious academic pursuit and a means of engaging the public. These dinosaur models at the Crystal Palace were groundbreaking in their merchandising, being sold as postcards, guide books, and replicas to a wider audience. The latter part of the 1800s witnessed a noticeable shift towards scientific restorations of prehistoric life in academic works and paintings. For instance, the publication of Louis Figuier's "La Terre Avant le Deluge" in 1863 showcased a series of paleoart pieces illustrating life across different eras. Illustrated by Édouard Riou, these works featuring dinosaurs and other ancient creatures based on Owen's interpretations set a standard for future academic publications depicting prehistoric life.

Figure 21. A classic depiction of Iguanodon battling Megalosaurus, in the style of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs engaged in combat, from La Terre Avant le Deluge a work containing 25 ideal views of Old World landscapes (Édouard Riou, 1865).

These art pieces and scientific discoveries were not only of dinosaurs and I'm sorry for mostly focussing on them up until now, so following are examples of other paleoart.

Figures 22A & 22B. (22A) Mammoth Reconstruction, based on a frozen carcass observed in Siberia by Boltunov (1805). Collected in the article Yedoma Permafrost Genesis: Over 150 Years of Mystery and Controversy. Frontiers in Earth Science by Shur, et al. (2022).

Figure 23. The basic body plans of all modern animals were set during the Cambrian Period, 542 - 488 million years ago (“Ocean Through Time” by Danielle Hall, Reviewed by Brian Huber, Smithsonian Institution)

Figure 24. These snails roamed the seafloor in this Carboniferous Period scene. (“Ocean Through Time” by Danielle Hall, Reviewed by Brian Huber, Smithsonian Institution)

Figure 25. Several sharks from the Carboniferous Period. Illustrated by Julius Csotonyi, in (“Ocean Through Time” by Danielle Hall, Reviewed by Brian Huber, Smithsonian Institution).

Figure 26. Nebraska Savannah, Late Oligocene to Early Miocene (24.8 to 20.6 million years ago) by Jay Matternes, 1961 (NMNH) (Smithsonian mag, 2019).

Figure 27. Alaskan Mammoth Steppe, Late Pleistocene (20,000 to 14,000 years ago) by Jay Matternes, 1975 NMNH

Figure 28. Entelodon (then known as Elotherium), the first commissioned restoration of an extinct animal by Charles R. Knight, 1894 (Stout 2005, p. ix.)

Figure 29. Fossil of a Smilodon populator at the Tellus Science Museum near Cartersville, Georgia

Figures 30, Smilodon populator by Charles R. Knight (1903) from the American Museum of Natural History.

This is important to remember because paleoart and fossil work has been recorded through paintings, carvings, and sculptures back to Ancient Greece, although even calling it "proto-paleoart" is a stretch because it likely wasn't a purposeful scientific study, where a Corinthian vase, painted sometime between 560 and 540 BCE, is thought to be a depiction of an observed fossil skull (Mayor, 2011). It was known as "the monster of Troy" who was fought by Heracles, and its head is said to resemble the skull of an extinct species of giraffid, the Samotherium; who's name translates to "beast of Samos" [which makes an automatic connection, whether intended or not] (Ellis, 2004: 6).

In different versions shown on different vases:

Heracles rescued Princess Hesione of Troy from the Cetus (Sea-Monster). The hero plies the monster with a volley of arrows from his bow. The Cetus is depicted as a serpentine beast with a gaping maw and jagged teeth (Figure 31).

Heracles battles the Trojan Cetus (Sea-Monster). The hero is naked and wields a fish hook in one hand. The monster is depicted as a shark-like beast with a spiny back and undulating tail. Several sea creatures surround it--a seal, two dolphins and an octopus (Figure 32).

Figure 31. P28.2 HERACLES, HESIONE & THE CETUS Archaic (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)(theoi.com).

Figure 32. P28.1 HERACLES & THE TROJAN CETUS, ca 530-520 B.C.Period, Archaic (Stavros S. Niarchos Collection, Athens)(theoi.com).

The much more commonly passed around fossil to mythological connection would have to be the Cyclopes, with the big hole in the middle being the nostril rather than the eye (Figure 33). As Witton and other researchers also point out, these ideas have never been substantiated in the academic community, with them just making an appearance in general popular culture [though that doesn't mean that we can rule it out completely] (Witton 2018: 18). Even if the ancient historical writings or drawings were completely incorrect in what the original fossils showed, the work and some scientific thought were put into the depictions and the stories that were shared with the populous.

Figure 33. Cyclops: Did elephant skulls inspire the Ancient Greek mythological figure? (ATHENS BUREAU for Greek City Times 2023)

Bestiaries

The Medieval practice of writing and illustrating bestiaries shows that even these manuscript collections were not the first examples of drawing creatures that we humans did not understand. It does, however, appear to be one of the earliest examples of paleoart using both zoology and archaeozoology, the science of how animals interacted with humans and how they played a role in our culture, based on the biology of creatures of the past or living in that particular present.

If someone has played Dungeons and Dragons or Pathfinder and/or spent time looking through the Monster Manual, that someone has encountered a bestiary. Within those collections, Games Masters and players alike are given descriptions of some of the backstories of the creatures within along with where they are found, how they typically act, a list of attacks, strengths and weaknesses, and their stats next to an illustration. That means that someone in that universe either comprised an amazing collection of descriptions of adventures who encountered them, or a scholar went out to their habitat and made a written documentary. Both have been done in our universe/plane of existence, so neither is THAT strange. But as stated in the previous section, Witton's list of recommendations is followed extremely closely. Even though it’s based on animals in a fictional world, it could count (sort of) as paleoart, especially since, most creatures are still alive, and especially for those that adventurers have to wait until level 20 to fight, many do harken back to the ancient past.

*If you want to read the original 5e Monster Manual you can either buy a physical copy, buy it on DnDbeyond, or find a PDF version (they are everywhere).

Figures 34-37. Cover and examples of pages from the D&D Monster Manual and the Pathfinder Bestiary (images below to their respective owners) (Amazon.com).

Moving towards the reality of medieval bestiaries, these illustrated compendiums included animals, plants, and even rocks (not fossils) and seemed to have inspired the backstory aspect of our current bestiaries by including a moral, mostly relating to Christianity and God in some way. But, while more commonly associated with the medieval monks in Europe there has been at least one found from China. It is not clear who the original author was, and was likely a summarized compilation of the research achievements of the previous dynasties’ scholars, but it has been attributed to the ancient emperor Yu the Great, the first emperor of the Xia dynasty (Strassberg 2002: 4). Several academics agree that it was more of a living document, with updates being made over the centuries due to the inclusion of 'history' of Xia dynasty that hadn't happened when it was thought to be originally written in the 4th century BCE (Lust 1996, Bagrow & Skelton 2009, Jao 2014). It was named Guideways Through Mountains and Seas [山海經 "Shānhǎi Jīng"] or Classic of Mountains and Seas which described and/or illustrated: stories from explorers, wizards, and alchemists, many Chinese myths and "more than 100 states, 550 mountains, 300 waterways, and the geography, terroir and natural products of the states. According to the statistics of the animals in the "Shānhǎi Jīng", there are as many as 277 species" within its "18 volumes, including 5 volumes of "Shan Jing", 8 volumes of "Hai Jing", 4 volumes of "Da Huang Jing", and 1 volume of "Hai Jing Jing",... [and] a total of about 31,000 words" (Lewis 2006, 2009).

Classic of Mountains and Seas illustrations:

Figures 38-39: Pages from volume five of the Classic of Mountains and Seas, in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

Figure 43. Plate LXI Woodblock print depicting Bingyi (冰夷), also known as Hebo (河伯). Housed in the National Library of China, Beijing. Created in China during the Ming Dynasty by Jiang Yinghao in 1597.

Figure 44. Panther, Bern Physiologus, 9th century

The first bestiary that historians have studied is from the tradition of Ancient Greece, with its popularity dating back to the 2nd-century Christian Greek volume called the Physiologus (Clark 2005). Around the year 400 CE the Physiologus was translated into Latin from Greek which then allowed it to later be translated into at least six other languages for readers across Europe and the Middle East. Like in the Chinese Shānhǎi Jīng, the Physiologus was a compilation of descriptions of animals, plants, and sometimes the land itself, allegorical stories and tales of morality (Scarborough & Kazhdan 1991). This compendium was not as objective or directly nature-based as Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia, with the first 10 books published by 77 CE with the rest of the 37 published after his death by his son, Pliny the Younger, or Aristotle's De Animalium in which he sets up the Scala Naturae. As Curely states "[the] Physiologus was never intended to be a treatise on natural history. ... Nor did the word ... ever mean simply "the naturalist" as we understand the term, ... but one who interpreted metaphysically, morally, and, finally, mystically the transcendent significance of the natural world" (Curely 1979: xv).

Figure 45. Folio 12v of the Bern Physiologus.

Another similarity to the Chinese Shānhǎi Jīng is that the original author is unknown, but it was probably collected throughout time in Alexandria due to its similarities with the works of Titus Flavius Clemens, aka Clement of Alexandria who lived in the 1st and early 2nd centuries (Scott 1998: 430-441). Over the centuries the original text has been translated multiple times into many different languages, with more illustrations being added. The following images are examples of pages from the earliest versions that still exist. This translation is called the Bern Physiologus, a "9th-century illuminated copy of the Latin translation of the Physiologus and was probably produced at Reims about 825-850" (Calkins 1983).

Figures 46-48. Illuminated page details from the 12th-century Aberdeen Bestiary

Figure 49. Monoceros and Bear. Bodleian Library, MS. Ashmole 1511, The Ashmole Bestiary, Folio 21r, England, (early 13th century).

Figure 50. "The Leopard" from the 13th-century bestiary known as the "Rochester Bestiary".

Because bestiaries are thought to be connected to the early works of fossils. The idea of the Lindwurm (Figure 53) was possibly conceived in writings of the time that were partially based on a skull found in a mine or gravel pit near Klagenfurt in 1335 of Coelodonta antiquitatis, the woolly rhinoceros, as the basis for the head, which remains on display today (Witton 2018: 18). The German textbook Mundus Subterraneus, by Athanasius Kircher in 1678, features many illustrations of giant humans and dragons that may have been informed by fossil finds of the day, many of which came from explored quarries and caves.

Figure 53. The Klagenfurt Lindwurm sculpture in Klagenfurt, Austria by Ulrich Vogelsang from around 1590.

Learning from Mistakes

Some of these creatures may have been based on the bones of large Pleistocene mammals common to these European caves, while others may have been based on far older fossils of plesiosaurs. Like the mammoth cyclopes, however, it's difficult to know for sure where ideas arose from. According to some researchers, the change from the typical dragon artwork of this time, which was shown to have the classically slender, serpentine dragon shape, in lieu of a barrel-like body and 'paddle-like' wings has been thought to have been the arrival of a new source of information, such as the speculated discovery of plesiosaur fossils in quarries of the Swabia region of Bavaria (Figures 54-5)(Abel 1939, Witton 2018: 19-21).

Figure 54. Letter concerning the discovery of the 1823 Plesiosaurus, from Mary Anning.

Figure 55. An 1869 life restoration of Elasmosaurus (with the head still on the wrong end) confronting the theropod dinosaur Laelaps (now Dryptosaurus) platyurus.

Figure 56. Gigantic plesiosaurs once swam the Western Interior Seaway in what is now Saskatchewan (photo by Mohamad Haghani/Alamy Stock Photo).

The 18th-century skeletal reconstructions of the unicorn are thought to have been inspired by the “discovery” of a chimaera made by Ice Age mammoth and rhinoceros bones found in a cave near Quédlinburg, Germany in 1663 (Figures 57 & 58). These artworks are of uncertain origin and may have been created by Otto von Guericke, the German naturalist who first described the "unicorn" remains in his writings, or Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the author who published the image posthumously in 1749, which is the oldest known illustration of a fossil skeleton (Witton 2018: 20–21, Ariew 1998). “The horn, together with the head, several ribs, dorsal vertebrae and bones were brought to the town's serene abbess”, Leibniz, lacking the ability to personally engage in fieldwork, placed his trust in eyewitnesses from the area. Consequently, he found himself dependent on the observations of those around him, leading him to delve into armchair speculation.

Figure 57. One of the posts on Twitter about the exhibit reconstructing the famous botched fossil reconstructions, a ‘joke’ that fooled a number of scientists of the time.

Figure 58. Valentini’s unicorn. Found in Drittes Budh/von allerhand Thieren pg 481.

Figure 59. Unicorn from 'the history of four-footed beasts and serpents' by Edward Topsell 1658

Figure 60. Camphur, a unicorn-like creature with webbed hind feet (Aldrovandi, Ulisse. 1642. ‘Monstrorum Historia’).

The idea of the unicorn already existed in medieval and older societies, but that can be a whole extra book. While unicorns themselves are an extreme example of what people can ‘build’ out of bones, especially to fool people who don’t know better, the lesson we can learn is to take a scientific eye to what we are looking at.

Conclusion

Science moves forward, ideas change, and that's the wonderful thing about intellectual progress. We look back at the ancient and mediaeval bestiaries, at the papers, illustrations, and sculptures up through the 19th and 20th centuries, and up to today and see that we make mistakes; we don't see the whole picture. Bestaries of any time were not perfect, far from it. But, we continue to try, to improve, to learn more. Life finds a way, and authors and artists have long sought to share the experience. The rich tradition of paleoart can be traced back to the bestiaries of ancient times. These vases, to carvings, to illuminated manuscripts not only served as a compendium of animal knowledge but also as symbolic representations deeply intertwined with mythological and religious beliefs. The reflexive topic demonstrates how today's society has continued to look at unknown creatures in our world and their place in scientific progress. At first, these animals were made from magic or myths of monsters or demons, but, with time, advances in study, and open-mindedness the work shows that it's the natural laws that govern us all.

Paleoart plays a significant role in communicating scientific understanding of prehistoric life to both the researchers and the public understanding of extinct species, particularly dinosaurs. It combines scientific evidence with creative interpretation, influencing both scientific ideas and public perception (Allmon & Ross 2000). What’s important is that paleoart evolves alongside scientific discoveries, with recent findings on feathered dinosaurs offering new creative possibilities while also constraining artistic license (Wang et al. 2019, McDermott 2020). The field bridges art and science, reflecting the state of paleontological knowledge at the time of creation and revealing the human story behind interpreting fragmentary remains (Hillesheim & Palace Dinosaurs 2022). Artists of today can draw inspiration from the intricate illustrations and fantastical descriptions found in bestiaries, continuing the legacy of bringing ancient creatures to life through art. By exploring the connections between paleoart and bestiaries, we gain a profound appreciation for how art has the power to transcend time and connect us with our past in meaningful ways. While paleoart enhances visitor understanding in exhibitions, curators must carefully evaluate its selection and application to avoid misleading interpretations (Wang et al. 2019). As palaeontology advances, paleoartists face the challenge of incorporating new scientific information while creating engaging visual representations of prehistoric life (McDermott 2020).

Additional Information:

*Paleontology is not connected to archaeology at all. Archaeologists are not designated to study dinosaurs. Palaeontology is a subset of either biology or geology (depending on the university) and archaeology is a subset of anthropology - a study of human culture. Archaeology (the study of ancient human culture) is also under the BA system rather than BS, but it varies depending on the university. I just love to study ancient life, in all its forms.

Like the other topics I've started to jump into, there's so much more that could be a whole book or more. I hope that I have just left someone with the idea to type paleoart or bestiaries into Google Scholar for themselves.

Check out this artist!! Liam Elward Paleoart @paleobyliam

And read these two articles:

1. 'Paleoart: the strange history of dinosaurs in art – in pictures' in The Guardian.

2. 'You Won't Be Able To Recognize These Modern Animals Drawn Like Dinosaurs' by Natasha Umer a writer at Buzzfeed News.

My biggest recommendations go to PBS Eons, YDAW (Your Dinosaurs are Wrong), and the wonderful podcast I love I Know Dino. They are all educational and entertaining and while I love rewatching Jurassic Park it doesn't inspire me as much as these YouTube channels do at this point in my life. Yes, reading scientific journals, as direct sources, is useful for the information, but some light viewing shouldn't be sneered at. Just follow the citations of the creators’ sources, to get more background.

Specifically, for more about Paleoart and its evolution, I'd watch An Illustrated History of Dinosaurs. This was what this article was going to be before I watched it, and thus, reworked the topic.

*AI can create its own crazy bestiary creatures, but that certainly takes our understanding of the natural work backwards.

Further Reading:

Fabbri, M., Wiemann, J., Manucci, F. and Briggs, D.E.G. (2020), Three-dimensional soft tissue preservation revealed in the skin of a non-avian dinosaur. Palaeontology, 63: 185-193. https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12470

"Meet the Master Muralist Who Inspired Today's Generation of Paleoartists" by Roger Catlin, 2019

Ocean Through Time: Smithsonian Ocean by Danielle Hall/Reviewed by Brian Huber, Smithsonian Institution

Representation and Aesthetics in Paleo-Art: An Interview with John Gurche (Koepfer & Gurche, 2003)

List of Medieval Bestiaries and Bestiary Families

"The Medieval Bestiary", by James Grout, part of the Encyclopædia Romana.

Debus, A.G., & Debus, D.E. (2002). Paleoimagery: The Evolution of Dinosaurs in Art.

Debus, A. A. (2003). Sorting fossil vertebrate iconography in paleoart.

Work Cited:

Abel, Othenio (1939). Vorzeitliche Tierreste im Deutschen Mthus, Brachtum und Volksglauben. Jena (Gustav Fischer).

Allmon, W.D., & Ross, R.M. (2000). An Art Exhibit on Dinosaurs and the Nature of Science. Journal of Geoscience Education, 48, 296 - 300.

Arbour, Victoria. (2018). "Results roll in from the dinosaur renaissance." Science: 611-611.

Ariew, R. (1998). "Leibniz on the unicorn and various other curiosities". Early Science and Medicine (3): 39–50.

Bagrow, Leo R. & Skelton, A. (2009). History of cartography. Transaction Publishers. p. 204.

Berta, A. (2021). Art revealing science: marine mammal palaeoart. Historical Biology, 33(11), 2897-2907.Calkins, Robert G. (1983).Illuminated books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Campione, Nicolás E., Paul M. Barrett, and David C. Evans. (2020). "On the Ancestry of Feathers in Mesozoic Dinosaurs."The Evolution of Feathers. Springer, Cham: 213-243.

Clark, Willene B.; McMunn, Meradith T. (2005). "Introduction". In Clark, Willene B.; McMunn, Meradith T. (eds.). Beasts and Birds of the Middle Ages. The Bestiary and Its Legacy. Nation Books: 2–4.

Curley, M. J. (1979). Physiologus. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN: 0-292-76456-1.

Ellis, Richard (2004). No Turning Back: The Life and Death of Animal Species. New York: Harper Perennial: 6.

Fabbri, Matteo, et al. (2019). "Three‐dimensional soft tissue preservation revealed in the skin of a non‐avian dinosaur."Palaeontology.

Guo, Pu. Shan hai jing (v.1). [China: s.n. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.886675.39088019548684

Hallett, Mark. (1987). "The scientific approach of the art of bringing dinosaurs back to life". In Czerkas, Sylvia J.; Olson, Everett C. (eds.). Dinosaurs Past and Present (vol 1). Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Hillesheim, B.J., & Dinosaurs, P. (2022). Palaeontologia Electronica Review: The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs Review by Ben Hillesheim.

Huttenlocker, Adam K., and C. G. Farmer. (2017). "Bone microvasculature tracks red blood cell size diminution in Triassic mammal and dinosaur forerunners." Current Biology 27.1: 48-54.

Ibrahim, Nizar, et al. (2020). "Tail-propelled aquatic locomotion in a theropod dinosaur."Nature: 1-4.

Koepfer, Diana L., and John Gurche. “Representation and Aesthetics in Paleo-Art: An Interview with John Gurche.”American Anthropologist, vol. 105, no. 1, 2003, pp. 146–148.JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3567324.

Lescaze, Zoë (2017). Paleoart: Visions of the prehistoric past. Taschen.

Lewis, Mark E. (2006). The Flood Myths of Early China. State University of New York. p. 64.

Lewis, Mark E. (2009). China's Cosmopolitan Empire: the Tang dynasty, Vol. 4 (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 202.

Liston, J. J. ( 2010). "2000 AD and the new ‘Flesh’: first to report the dinosaur renaissance in ‘moving’ pictures."Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 343.1: 335-360.

Lust, John (1996). Chinese popular prints. Brill Publishers. p. 301.

Mantell, Gideon A. (1851). Petrifications and their teachings: or, a handbook to the gallery of organic remains of the British Museum. London: H. G. Bohn.

Manucci, Fabio & Romano, Marco. (2022). Reviewing the iconography and the central role of ‘paleoart’: four centuries of geo-palaeontological art. Historical Biology. 35.

Mayor, Adrienne (2011). The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times (second edition). Princeton University Press.

McDermott, A. (2020). Dinosaur art evolves with new discoveries in paleontology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(6), 2728-2731. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2000784117

Scarborough, John; Kazhdan, Alexander (1991). "Physiologos". In Kazhdan, Alexander(ed.).The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1674.

Schaller, George B.; Crawshaw, Peter Gransden Jr. (1980). "Movement Patterns of Jaguar". Biotropica.12(3): 161–168. doi:10.2307/2387967. JSTOR2387967.

Scott, Alan. (1998). "The Date of the Physiologus"Vigiliae Christianae 52.4. November: 430-441.

Shur, Y. & Fortier, Daniel & Jorgenson, M. & Kanevskiy, Mikhail & Schirrmeister, Lutz & Strauss, Jens & Alexander, Vasiliev & Jones, Melissa. (2022). Yedoma Permafrost Genesis: Over 150 Years of Mystery and Controversy. Frontiers in Earth Science. 9. 10.3389/feart.2021.757891.

Strassberg, Richard E., ed. A Chinese bestiary: strange creatures from the guideways through mountains and seas. Univ of California Press, 2002.

Taquet, P. and Padian, K. (2004). "The earliest known restoration of a pterosaur and the philosophical origins of Cuvier’s Ossemens Fossiles." Comptes Rendus Palevol, 3(2): 157-175.

Taylor, Michael P. (2006). "Dinosaur diversity analysed by clade, age, place and year of description." 9th [Ninth] Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems. Cambridge Publications.

Wang, Q., Chandrasena, L.L., & Lei, Y. (2019). A critical review of the application of paleo-art in paleontological exhibition – a case study of the Dinosaurs of China exhibition in Wollaton Hall and Lakeside Arts, Nottingham. Museum Management and Curatorship, 34, 521 - 536.

Witton, Mark P.; Naish, Darren; Conway, John (2014). "State of the palaeoart"(pdf). Palaeontologia Electronica. 17 (3): 5E.

Witton, Mark P. (2016). Recreating an Age of Reptiles. Crowood Press.

Witton, Mark P. (2018). The Palaeoartist's Handbook: Recreating prehistoric animals in art. U.K.: Ramsbury: The Crowood Press Ltd.

Xing, Lida, et al. ((2017). "A mid-Cretaceous enantiornithine (Aves) hatchling preserved in Burmese amber with unusual plumage." Gondwana Research 49: 264-277.