The Ballgame

Archaeological evidence is the main source of knowledge about the Maya ballgame, which was played at various levels from sport to ritual. In the Late Classic period (600-900 CE), the sport evolved into a structured ceremony, with Maya rulers participating in tournaments held at ceremonial sites. Even though there is little understanding of the game, numerous royal tombs display signs of ball playing, including sculptures on steps and hieroglyphic writings documenting the game. In addition, most city sites contained a ball court, generally of slightly slanted walls and hoops rebuilt flanking the middle court area. The connection between ballplaying scenes and the architectural backdrop is still fascinating, as there are signs indicating that the sport was celebrated in grand amphitheatres, though generally played in small courts next to a temple. Understanding the historical significance of the ballgame in Classic Maya society relies heavily on the analysis of Maya art and hieroglyphic evidence. (Miller & Houston 1987: 48, Lentz et al. 2024).

The Maya ballgames held great mythological significance in ancient Mesoamerican cultures. It was not just a sport but a ritual with deep symbolic meaning. The game symbolized the eternal struggle between opposing forces such as day and night, life and death, and the sun and the moon. The ballcourt itself represented the mythological structure of the universe, with the players acting out the cosmic battle through their movements and the ball representing the journey of the celestial bodies while also reenacting the creation of the universe. The outcome of the games was believed to impact the balance of the world, ensuring fertility, prosperity, and the favor of the gods for the community.

Cartoony Introductions

As a 90s kid growing up in America, Road to El Dorado (which came out in 2000, when I was 8) was probably my introduction to the world of the Maya. I won't dive into the movie much if at all [if I can help it]. Still, when I learned about the area's history, mythology, and art, I was pleasantly surprised that a lot of research went into the art and the backgrounds and even hints in the story that are made obvious when reading the mythology. It's not perfect and it can still be culturally insensitive to a still-living group of people, so I'm sorry, but I still enjoy watching this movie.

The main story is based on a couple of Spanish men, Miguel and Tulio pretending that they are gods to scam the people. The “whole white people as gods” idea is a truly awful trope that was radically spread by Cortez and the missionaries after landing in the new world and being welcomed, if even for just the shortest time. But even if 100% true, the basis may be in the myths themselves, in which gods are set to return from across the seas in the East, the heavens, after going through the Underworld (Xibalba in the West). This lies within the animated story along with the white saviour trope, in which our two main white male characters are misidentified as the Hero twins and in one scene they have to play the significantly culturally recognized ballgame, known as Pok-a-Tok, which the original hero twins invented (Little, n.d.).

In the movie, the stela outside the entrance depicts the Twins riding the Plumed- or Flying Serpent God Quetzalcoatl [the "tl" is pronounced ' 'k ' by the way with a slight l after the guttural stop], K’uk’ulkan in Yucatec Mayan, or Qʼuqʼumatz in K’iche Mayan. And in the lower right corner is a maiden offering the Gods a head. This is supposed to reflect what happens later in the scene and is the story’s inciting incident. This demonstration of research by the artists is neat because this feels reflexive of the daughter of one of the Lords of Xibalba returning the head of the Hero Twins' father after they were brought back to life.

Figure 2. The stela of the Hero Twins riding on the back of K’uk’ulkan with a priestess making an offering (Road to El Dorado - Dreamworks 2000).

Figure 3. The protagonists are led on horseback to the city with Chel still on the ground in front of the Hero Twins stela (Road to El Dorado - Dreamworks 2000).

The gods were not shown to bleed in Mayan artwork. Whenever snakes are depicted snake-ing from a body, generally human sacrifices, it means they are showing gushing blood. Blood was/is extremely important, it is chu’lel * or “life-force” after all, and bloodletting (piercing the penis for men and running a thorny rope through the tongue for women) was a normal thing for royalty to do (Haines, Willink, & Maxwell 2008; Houston & Stuart 2015). But for the normal games, it wouldn’t make sense for a good player to be killed at the end of every game (Helmke in Geggel 2022). Tzenkel Kan was taking the Popul Vu story too literally.

Figure 4. Close-up shot of Miguel bleeding after being hit in the face during the ballgame (Road to El Dorado - Dreamworks 2000).

Figure 5. Tzekel-Kan’s bloody hand in front of a stela (Road to El Dorado - Dreamworks 2000).

Figure 6. Tzekel-Kan in a skull-like mask (Road to El Dorado - Dreamworks 2000).

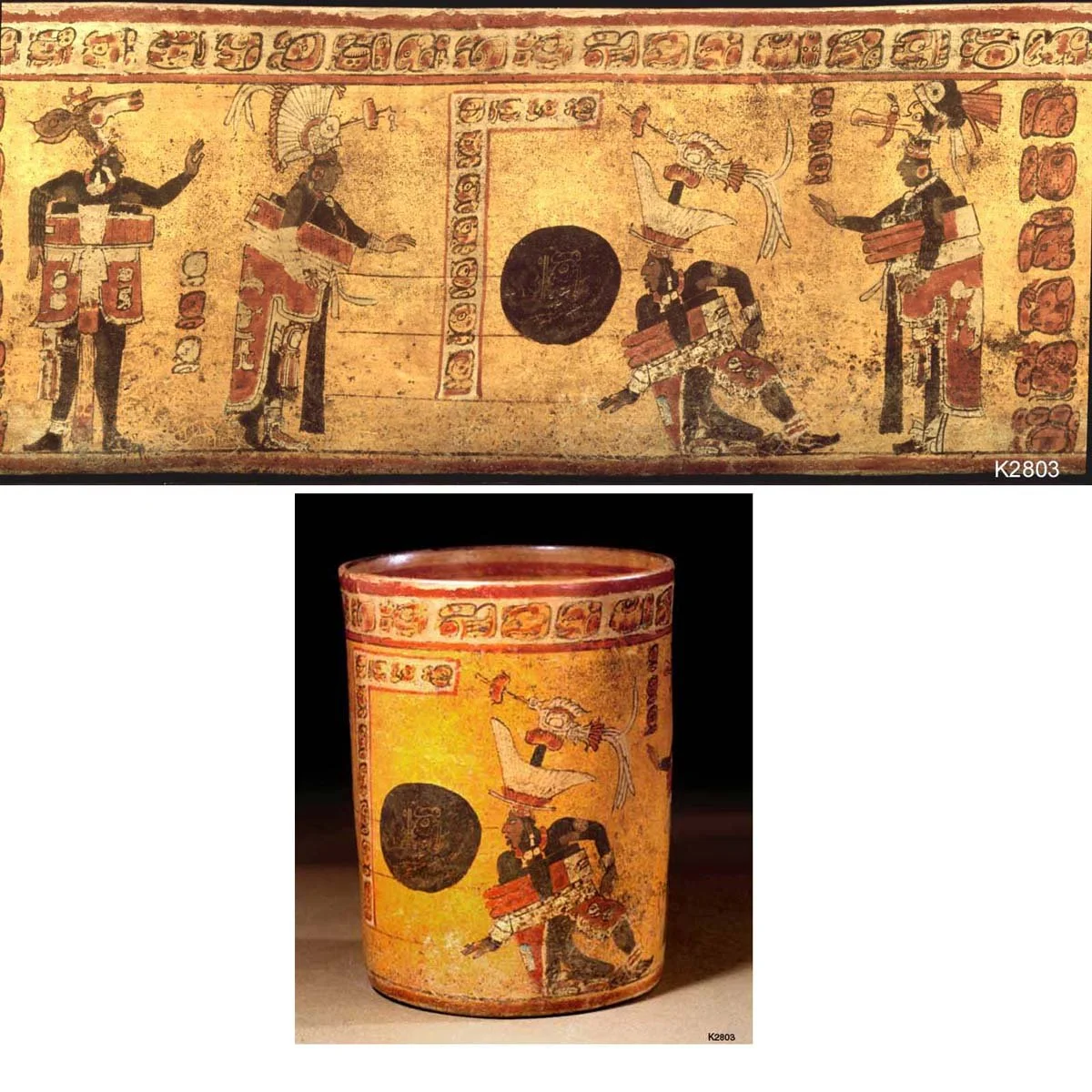

Figure 7. This relief on limestone dating to A.D. 700-800 shows two Maya men, dressed in elaborate costumes, playing a ritual ballgame. (Image credit: Ada Turnbull Hertle Fund)

Figure 8. A Maya vessel, dating from about A.D. 600-1000, shows a Maya ballplayer wearing a thick protector to shield his torso from injury. The ballplayer dives to intercept the ball, which hovers in front of his face. (Image credit: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James C. Gruener)

The Walls are too High

Figure 9-11. Screenshots (Chief Tannabok's Warriors), Tulio, and an overview of the ballcourt captured from the movie Road to El Dorado (Dreamworks 2000).

This movie example of the game is overblown, but gods can do anything, I guess. The human warriors they are playing against wouldn't stand a chance and not because they're posing as the literal gods who invented the game either. The high vertical wall ballcourt is most likely modelled on the ritualistic ball court at Chichen Itza in northern Yucatan, Mexico. The pictures down below are for comparison.

Figure 12. Chichen Itza's massive ballcourt (Photo by Whitehouse 2013).

Figure 13. The hoop on the right side (when entering from the open side (Photo by Whitehouse 2013).

Figure 14. Overview of some of the carvings depicting the mythology behind the game (Photo by Whitehouse 2013).

Figure 15. Carvings illustrate (left to right) a warrior in armour holding a decapitated head ball with a skull inside it in front of a decapitated man on his knees. Snakes are erupting from the man's neck, these snakes represent blood (Photo by Whitehouse 2013).

Figure 16. The tzompantli (skull rack), stone carved heads symbolic of the practice of decapitation after the game (Photo by Whitehouse 2013).

According to Braswell in the 2013 field school, this massive ballcourt was not played on, it was a symbolic and ritualistic arena where special events would take place, such as kings from distant cities coming to be crowned and recognized. This overarching hierarchy brought the separate Maya communities together under a single religion and into the larger Maya Empire, especially in the Classic Maya period and beyond. In the case of the normal version of the court that people could ritually play out the story of the Hero Twins, a smaller, slanted version looks like the examples below.

Figure 17. Play looks more like this (Little n.d.). Pok-A-Tok: The Ancient Maya Ball Game

Examples of reconstructed ballcourts from sites in Mexico and Guatemala (Photos by Whitehouse 2013 & 2014).

The Rules

Diego Durán, a Dominican friar, never saw the Mesoamerican ballgame firsthand. Instead, he interviewed indigenous elders, providing valuable insights into the game. According to Durán's writings from the early 1570s, the Maya ballgame involved two teams trying to keep the ball in constant motion, hitting it with their hips or wooden paddles in certain regions. Points were scored by driving the ball into the end zone or if the opposing team made a mistake (Helmke). On occasion, members of the royal family would engage in games, occasionally asking rulers from nearby regions to participate to demonstrate loyalty (Helmke). The games were popular and heavily attended whether it was royal or ordinary athletes participating. The games drew large crowds, with some spectators even losing large bets, clothes, or their lives in the case of prisoners used in gladiatorial rituals.

For the Maya, the ballgame served various purposes, including being a sport for youth, a public spectacle, a cosmic conflict reenactment, and even a game played by the gods to create the world (Miller & Houston 1987). The earliest known ball court dates back to 1400 BCE in Paso de la Amada, Guatemala, but the oldest artifacts of the game may be rubber balls from the Gulf Coast of Mexico dating back to 1600 BCE, according to the Met (Miller & Houston 1987, Geggel 2022). The Spanish, upon encountering the ballgame in Mesoamerica, were intrigued and even brought indigenous players to Spain to demonstrate it to King Charles V. However, due to its association with human sacrifice, the Spanish eventually banned the game as part of their conquest of the region.

Regarding the hoops, Durán mentioned that on occasion the ball would pass through a hoop positioned in the middle of the alley. Helmke stated that if that occurred, the entire game would come to a halt and the individual who scored the ball would be celebrated as the winner. However, he did not mention that as the objective of the game. He mentioned that it could occur occasionally and it was extraordinary. In addition, Helmke mentioned that the majority of ball courts in the Maya region do not contain hoops (Helmke in Geggel 2022).

If a player does make a point that wins the game the audience would run away because they would've had to give the winners anything they wanted from what the rich audience members were carrying (Braswell 2013). I still am not sure whether the losers were sacrificed or the victors. Cause as a sacrifice the winners would have been heroes and more valuable, like when the Hero Twins killed themselves. But if a king was playing for ritualistic reasons, and he would win [I assume], respectful of the Heroes, he wouldn't have been killed. Plus if the above point was true, at least sometimes, then the rich who were watching the game wouldn't have to lose any money.

Human sacrifice

Human sacrifice would not have been universally condemned and could have been viewed positively following military triumphs, much like in the popularity of the gladiator battles in Ancient Roman arenas. In ancient Mesoamerica, the relationship between sports and sacrifice is complex and diverse. While sports in ancient Mesoamerica were well-liked and sometimes included sacrifices, unlike gladiatorial combats, these offerings were not a central part of the game. The concept of regular sacrifices following the match may have come from the Popol Vuh. This Maya creation myth began as oral tradition later written by an indigenous leader and then recopied by Dominican friar Francisco Ximénez in the early 1700s. The narrative includes underworld gods defeating humans in a ballgame and cutting off their heads, then humans emerging victorious in a second match and dismembering the Lords of Xibalba. Not all of the mythology is as reflexive or true to life, especially as morality changes with time. Artistic designs on a few ball courts with skulls and bones also contributed to the myth of "human sacrifice." It is uncertain whether these references should be interpreted literally. In general, the relationship between sports and sacrifice is intricate and subject to different understandings. (Geggel 2022).

The Myth of the Hero Twins and Their Role in Creation [Codified]

The K’iche Maya of Guatemala wrote the Popol Vuh (“Book of Counsel” or “Book of the People”) on paper bark during the colonial period (Foster and Mathews 2005: 188; Drury 2002: 253, Coe 1999: 72, Martin and Grube 2000: 15, 130, 221). This book reiterates the Maya oral traditions and describes the Maya people’s creation myth and cultural history (Coe 2005: 65, Coe 1999: 72, 99-100, 200, 220-2, 226, 249, 268).

One version tells of a couple of grandfather and grandmother creator gods named Xpiyacoc and Xmucane who originally fashioned the Popol Vuh from a watery space or void. Even though the universe had already been through a series of creations and destructions, each subsequent new world was imperfect. The gods had created the divided universe and filled the earth with birds, animals, fish, reptiles, and forests to sustain themselves, but the gods needed more than nourishment. The gods also needed worship, which animals couldn't provide so, therefore, they began creating humankind (Foster and Mathews 2005: 184). The task of creating humankind was full of issues though. The gods initially tried to create humans from clay and wood. Still, these beings were doomed because they could not offer the gods what they desired, "which was worship, admiration, and blood" (Coe 2005: 65). Because early tests were unsuccessful. The gods still required offerings and prayer to sustain them, so they tried more "human" experiments.

Skipping ahead in time, towards the end of the creation cycle, a great flood covered the entire world. The sky fell on the earth, and the stars, the moon, and the sun were extinguished. This caused darkness to fall and from this "an arrogant and hideous bird-monster declared and proclaimed himself the newborn sun and moon" (Coe 2005: 65). Next and not necessarily connected, the grandmother creator god, Xmucane, gave birth to a pair of twins [not the hero twins]. One of the newborn twins was the maize god, Hun Hunahpu aka One Ajaw or Head-Apu I' (a calendrical name), and his brother Vucub Hunahpu (literally Seven-Hunahpu) who, according to Coe, (2005), was a mere double, companion, or reflection of Hun Hunahpu (Coe 2005: 65, PenDragon n.d., Tedlock 1996). In some versions of the myth Seven Hunahpu later married and fathered two sons named Hun Chuwen and Hun Batz (Coe 2005). But, in others, Seven Hunahpu had no children and "remained a boy" while Hun Hunahpu married and had four children; Hunahpu, Xbalanque, One Monkey, and One Artisan. Two of these were the Hero Twins; Hunahpu and Xbalanque (Tedlock 1996; Brock 2018), but they wouldn't be "born" until the story moves into the underworld.

According to Coe (2005: 65), further along in the creation story Hun Hunahpu and Seven Hunahpu were extremely fond of, and very good at, playing a game of a ball, bouncing the rubber ball up and down all day (Zaccagnini 2003: 17). The Lords of Xibalba, ‘The Place of Fright’ (the underworld), were annoyed and constantly enraged at all the noise from their upstairs neighbors. The lords of Xibalba, therefore, came up with a plan to trick and trap the twins by inviting them to play a game of ball against the lords (Tedlock 1996). This worked and once they were trapped the lords inflicted a series of horrid tests and experiments upon the brothers in several different fear-inducing chambers (Coe 2005: 65). Afterwards, the twins were sacrificed and the Maize God’s head, specifically, was hung from either a calabash or a cacao tree.

After some more time passed, one of the daughters of an underworld god walked under the tree and noticed the head of Hun Hunahpu hanging from it and it spoke to her (Coe 2005: 65; Tedlock, 1996). [Not sure what it said to convince her, but...] she raised her hand and it spat on her causing her to become impregnated. Six months later the still pregnant daughter of the underworld lord was kicked out in disgrace since she was carrying a child of the Maize god (Coe 2005: 65). On the surface the creator-god-grandparents sheltered her as they would also soon be the grandparents of her underworld children, the Hero Twins, named Hunahpu and Xbalanque (Coe 2005: 65, Tedlock 1996). They were blow-gunners, hunters, ball players, and tricksters. The Hero Twins' half-brothers, Hun Batz and Hun Chuwen, were jealous of them and tricked them into becoming monkeys or monkey-men (Coe 2005: 65, Tedlock 1996). The monkey-men half brothers were later considered demi-gods and patrons of music, dancing, writing, carving, and in fact, all of the Maya arts; so that plan of 'revenge' or bringing them down to size didn't work out (Coe 2005: 65).

The Hero Twins worked to rid the world of monsters, killing the bird monster and two other monsters, which were a volcano and the creator of earthquakes (Coe 2005: 66). And then the gods watched and waited for the Hero Twins to defeat the underworld gods of death and decay, which would allow the creator gods to receive the best materials to make humankind (Foster and Mathews 2005: 184; Tedlock 1996).

Like their father and uncle before them, they decided to play a ball game in the makeshift ball court. Again, such a ruckus was made on the underworld roof that the twins were summoned to the underworld and placed in the horrifying death chamber, but unlike their father and uncle they were able to turn the tables on the death lords by tricking them into playing the ballgame and defeated them (Coe 2005: 66). However, the Hero Twins knew they would suffer the same fate as their uncle and father before them, so, they committed suicide instead (Coe 2005: 66). Fortunately, the gods of the earth were saddened in the wake of their deaths so the Hero Twins were resurrected and promptly slayed the death lords and resurrected their father Hun Hunahpu the Maize God (Coe 2005: 65). With this victory the world tree [the ceiba] grew up from Xibalba; splitting the surface of the Earth in two, becoming a great new ballcourt, and the lifting up the sky giving the earthly gods a space and time to focus on creating the perfect human beings again, creating them out of a doughy mixture consisting of ground maize and blood who were the Maya and they were suitably grateful to the gods for their creation (Foster and Mathews 2005: 184).

The many times that the game would be played was more of a historic/mythic reenactment of this momentous story. And, when human sacrifice was involved, as depicted in the carving of skull racks, it would be done in a way that was both religious and political (Zender 2004). For example, if a territory had recently been conquered the new captive soldiers would be forced to play. As they could be injured, hindered, or forced to lose, they would have been sacrificed after the game to demonstrate the might of the victorious Ajaw and his city.

Where the Game Was Played

But, as one could see, it wasn't just the myth that spread.

"[T]hey appear outside the Maya area at Teotihuacan, El Tajin, Tenochtitlan, and in various central Mexican codices [...] which began at the Olmec site of La Venta, [...] with the Maya serving as the prime example. Elements of this cosmo-political pattern were so widespread [...] that this overall pattern served as the ideological foundation of Mesoamerican civilization from the time of the Olmec until the coming of the Spaniards."

(Gutierrez 1996).

From the Olmec heartland in Oaxaca, and expanding south-eastward through Chiapas (De Montmollin 1997) southern Mexico, down through Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Belize, the ballcourts show up everywhere (Healey 1992, Schultz, Gonzalez, & Hammond 1994, Chase 2016). Influencing various intertwining local cultures, including, but not limited to, the Mixtec, Zapotec, Classic Veracruz, Xochicalco, and Toltec all had ballcourts in their cities of various sizes, but with generally the same I-shape (Quirarte 1975: 205-210). Even the earliest versions had these identifiable traits (Blomster & Chávez 2020). This is also why it is thought, by archaeologists specializing in the region, that the game Hohokam is the Southwestern Indigenous Americans' version of the ballgame, where they are found mostly in Arizona (Odenkirk 1971: 215, Kohler, Fish, S. K., Fish, P. R., & Erickson 1992: 288, Witze 2018).

Figure 35. A Maya ballcourt in Copan, Honduras. (Image credit: Shutterstock from Geggel 2022).

Figure 36. Classic I-shape ball court in Cihuatan site, El Salvador (Photo by Samuel-san Miguel: Juego de Pelota).

Figure 37. One of the ballcourts at Xochicalco has the characteristic I-shape and the rings are set above the apron at center court. On the equinox, the setting sun shines through the ring. (Uriarte 2006:23).

Figure 38. Basic ballcourt terminology, but not all ballcourts have all these surfaces (Image by Madman2001).

Figure 39. Cross sections of some of the more typical ballcourts. Jacinto Quirarte has classified Copan, Uxmal, and Xochicalco as Type I, Monte Alban as Type II, Chichen Itza as Type III, and Toluquilla as Type IV (Image by Madman2001).

Figure 40. Two players in an I-shaped court facing each other across a row of skulls and rings flank the sides. Page 68, Codex Magliabecchiano. Postconquest manuscript. Drawing by Mary Ellen Miller (Miller & Houston 1987: 47).

Figure 41. Early ballcourts in Mesoamerica - Comparison of early ballcourt cross sections (to scale), with earliest on top, with plan views (not to scale) from Paso de la Amada and La Laguna (Blomster, & Chávez 2020; Blake 2011; Carballo 2016).

Helmke explained that like dialects, the rules of ballgames varied across different locations. However, all ballgames were played on a capital I-shaped field called a playing alley, typically made of adobe or smooth polished plaster. Falling on the field could be painful due to its hard surface. The end zones were marked at the top and bottom of the "I," where players could score. Sloped terraces on each side helped keep the ball in play. The angle of the slope affected the pace of the game and how the ball bounced. Most ball courts are around 65 feet long (20 m), or about five times shorter than a football field, much smaller than the 316-foot long and 98-foot wide (96.5 meters by 30 m) court at Chichen Itza.

Conclusion

Similar to gladiator bouts in ancient Rome, there would likely have been an interest in the spectacle of the act as well as the pride that would follow a military victory. The mythology of the Maya ballgame holds a significant place in worldwide culture due to its rich symbolism and historical importance. The ballgame was not merely a sport but a ritual reenactment of the sacred Maya creation story, often ending in sacrifice. The game symbolized the eternal battle between the forces of good and evil, with the outcome believed to affect the balance of the universe. Today, the legacy of the Mayan ballgame lives on in various forms, inspiring art, literature, and even modern sports. Of course, a movie, animated or not, is going to get it right, but the thought and work put into the scene (and really the whole movie) just goes to show that its enduring significance serves as a reminder of the deep connection between ancient traditions and contemporary cultures around the world.

Aside

* Chel is the name of the woman who couples with Tulio, she is the one who gives life to their scheme, and Chul also means soul. Just found more connections more intriguing. While chu’lel means “life-force” and chel means “rainbow” and is part of the name of the creation goddess Ixchel.

Work Cited

Blake, M. (2011). FIVE. Building History in Domestic and Public Space at Paso de la Amada: An examination of Mounds 6 and 7. In Early Mesoamerican Social Transformations (pp. 97-118). University of California Press.

Blomster, J. P., & Chávez, V. E. S. (2020). Origins of the Mesoamerican ballgame: Earliest ballcourt from the highlands found at Etlatongo, Oaxaca, Mexico. Science Advances, 6(11).

Brock, Zoë. (11 May 2018). "Popol Vuh." LitCharts. LitCharts LLC. Web. 29 Apr 2021.

(11 May, 2018). "Popol Vuh Characters: One Hunahpu." LitCharts LLC. Retrieved April 16, 2021. https://www.litcharts.com/lit/popol-vuh/characters/one-hunahpu.

(11 May, 2018). "Popol Vuh Characters: Seven Hunahpu." LitCharts LLC. Retrieved April 16, 2021. https://www.litcharts.com/lit/popol-vuh/characters/seven-hunahpu.

Carballo, D. M. (2016). Urbanization and religion in ancient central Mexico. Oxford University Press, USA.

Chase, A. S. (2016). Districting and urban services at Caracol, Belize: Intrasite boundaries in an evolving Maya cityscape. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology, 13, 15-28.

Coe, Michael D and Koontz, Rex. (2002). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. [Fifth ed]. Thames & Hudson. London.

Coe, M. D. (2005). The Maya. United States: Thames and Hudson.

Danien, E. C., Sharer, R. J. (1992). New Theories on the Ancient Maya. United States: University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated.

De Montmollin, O. (1997). A REGIONAL STUDY OF CLASSIC MAYA BALLCOURTS FROM THE UPPER GRIJALVA BASIN, CHIAPAS, MEXICO. Ancient Mesoamerica,8(1), 23-41. Retrieved April 30, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26307210.

Geggel, L. (2022, August 17). Did the Maya Really Sacrifice Their Ballgame Players? LiveScience. https://www.livescience.com/65611-how-to-play-maya-ballgame.html.

Gutierrez, M. E. (1996). The Maya ballcourt and the Mountain of Creation: myth, game, and ritual (Doctoral dissertation).

Haines, Helen R, Willink, Philip W and Maxwell, David. (March 2008). Stingray Spine Use and Maya Bloodletting Rituals: A Cautionary Tale. In ‘Latin American Antiquity. Vol 19, no 1. : 83-101.

Healy, P. (1992). THE ANCIENT MAYA BALLCOURT AT PACBITUN, BELIZE. Ancient Mesoamerica,3(2), 229-239. Retrieved April 30, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26307139.

Houston & Stuart (2 January 2015). "Of gods, glyphs and kings: divinity and rulership among the Classic Maya". Antiquity. 70 (268): 289–312.

Kohler, T. A., Fish, S. K., Fish, P. R., & Erickson, C. L. (1992). A JOURNAL OF INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES. Agriculture and society in arid lands: a Hohokam case study, 13(4), 288.

Lentz, D. L., Hamilton, T. L., Meyers, S. A., Dunning, N. P., Reese-Taylor, K., Hernández, A. A., ... & Weiss, A. A. (2024). Psychoactive and other ceremonial plants from a 2,000-year-old Maya ritual deposit at Yaxnohcah, Mexico. Plos one, 19(4), e0301497.

Little, D. (n.d.). Pok-A-Tok: The Ancient Maya Ball Game | AMA Travel. AMA Travel. https://www.amatravel.ca/articles/pok-a-tok-ancient-mayan-sport.

Miller, M. E., & Houston, S. D. (1987). The Classic Maya ballgame and its architectural setting: a study of relations between text and image. RES: Anthropology and aesthetics, 14(1), 46-65.

Odenkirk, J. E. (1971). " Pok-Ta-Pok"-A Ceremonial Sport of the Hohokam Indians of Arizona?. Recarch; Sociology; Teacher Education; Teaching, 215.

Schultz, K., Gonzalez, J., & Hammond, N. (1994). CLASSIC MAYA BALLCOURTS AT LA MILPA, BELIZE. Ancient Mesoamerica,5(1), 45-53. Retrieved April 30, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26307183.

Tedlock, Dennis. (1996). Popol Vuh. Simon and Schuster, New York.

Quirarte, Jacinto (1975). "The Ballcourt in Mesoamerica: Its Architectural Development". In Alana Cordy-Collins; Jean Stern (eds.). Pre-Columbian Art History: Selected Readings. Palo Alto, CA: Peek Publications. pp. 63–69. ISBN 0-917962-41-9. OCLC 3843930.

Tokovinine, A. (2002). Divine patrons of the Maya ballgame. Mesoweb.

Uriarte, Maria Teresa (January 2006). "The Teotihuacan Ballgame and the Beginning of Time". Ancient Mesoamerica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 17 (1): 17–38.

Witze, A. (Spring 2018). "The Mystery Of Hohokam Ballcourts". American Archaeology, Vol. 21 No. 1. Web https://www.archaeologicalconservancy.org/the-mystery-of-hohokam-ballcourts/

Zender, M. (2004). Sport, Spectacle and Political Theater: New Views of the Classic Maya Ballgame. The PARI Journal, 4(4), 10-12.

Further Reading

("The Maya Codices - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org).

Chase, A. S. (2016). Districting and urban services at Caracol, Belize: Intrasite boundaries in an evolving Maya cityscape. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology, 13, 15-28.

Fields, Virginia M. [Ed] (1991). Olmec Bloodletting: An Iconographic Study. In ‘Sixth Palenque Round Table. University of Oklahoma Press. Norman.

PenDragon, J. (n.d.). An Interpretation of Ancient Maya Blood Rituals: The Hero Twins Creation Myth.

Sharer, R. J., Danien, E. C. (1992). New Theories on the Ancient Maya. United States: University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated.

Tiesler, Vera and Cucina, Andrea. (2007). New Perspectives on Human Sacrifice and Ritual Body Treatments in Ancient Maya Society. Springer. New York.

Wilcox, D. (1991). The Mesoamerican Ballgame (p. 101). D. R. Wilcox, & V. L. Scarborough (Eds.). Tucson: University of Arizona Press. from: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Mesoamerican_Ballgame/v5IlEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0&bsq=ballcourt.