All the Chimaera

Chimaera was never just the name of a single creature that was suffocated with lead lead-tipped spear by Bellerophon in Greek mythology. One very quick search for Chimaera on Google and/or Google Scholar leads one to hundreds of thousands of results. Maybe one out of a few hundred will have anything to do with mythology at all as most follow the newer meanings and the updated uses of the word, "an organism containing a mixture of genetically different tissues, formed by processes such as fusion of early embryos, grafting, or mutation" (Oxford dictionary). But even before the existence of the name, there were mythological creatures in hundreds of cultures that would fall under this descriptive banner. Of course, there is also the archaic genus of cartilaginous fish Chimaera and Grotesque architecture, the architectural style that features gargoyles aka grotesques (Linnaeus 1758; Rebold Benton & Janetta 1997). When looking a the definition through the lens of paleontology, a chimaera is defined as a fossil reconstructed by combining features from more than one single species (or genus) of animal, one example of which is famously Protoavis (Figure 1)(Chatterjee 1991; Chiappe 1995; Zhou 2004).

Figure 1. Protoavis paratype skeletal remains pieces of skull appear like those of a coelurosaur, while the femur and ankle bone suggest affinities to non-tetanuran theropods and at least some vertebrae are most similar to those of Megalancosaurus, a drepanosaurid. (Chatterjee 1991)

Figure 2. "Fossil skeleton of a bird-like reptile of the genus Archaeopteryx." The real, one full skeleton, of a 'proto-avis'; (https://prints.sciencesource.com/featured/1-archaeopteryx-fossil-james-l-amos.html).

Figure 3. Two-Colored Rose Chimera by Raquel Baranow

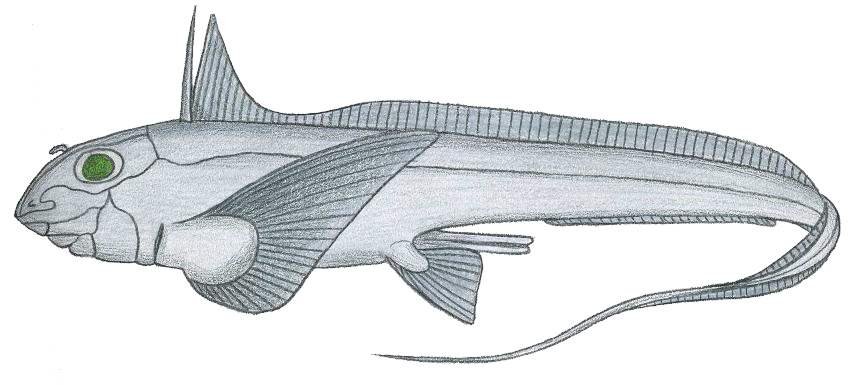

Figure 4. Chimaera Cuban reconstruction drawing by I, Tambja

Figure 5. A deep-sea chimaera or ghost shark(sense 7; species unidentified) from the Celebes Sea by NOAA and the deep-sea submersible Little Hercules.

Examples of Grotesques:

Another definition, which is apt, though possibly not the most relevant, is “a thing that is hoped or wished for but is illusory or impossible to achieve” (Oxford Dictionary). This one seems to be an attempt to build a definition from the origin story. In this way, future generations can learn that while Bellerophon thought that killing the Chimera would help him reach his goal of heroics, and maybe not be killed by his extended family, it was all a trick. He was only ever sent off to die and his heroics were illusions covering his hubris. As the saying goes, pride comes before the fall.

Chimera are a human way of explaining anything that doesn't fit into one definition or strata, making something a dangerous other. Having to explain mixtures of genetics or fossils, and, like bestiaries, were likely partially the predecessors of scientific development. Humans could be trusted to invent explanations for anything out of the ordinary, to keep people in line, or to create inexplicable heroes, by making a man-eater in the surrounding mountain forest. More recently, and included in tales from older mythos, it seems that the varying definition is almost fighting against the oldest beliefs that anything would be impossible or, more importantly, inherently a monster.

Popular Imagery

The most common visual in popular culture and many stories in Greek or Roman myth, or a Dungeons and Dragons bestiary (Figures 10-13), is not the only version of chimaera. She or they are powerful beings that are a heterogenous mixture of scientific discovery, myth, and plain old human curiosity and discovery, which is more a mixture of the previous two, a true chimaera.

The Greek Chimera

In the ancient Greek mythos Bellerophon, a hubristic hero, was sent on a suicide mission by King Iobates of Lycia to go kill the Chimera. One wonders how or why they determined in the mythos whether it was female, but as explained earlier, that's defined in the etymology of "she-goat" and plays into the mythology. She is sometimes credited with giving birth to the Greek Sphinx, a creature that is explored later (Kerenyi, 1959: 82; Becchio & Schadé, 2006). Being the child of Typhon and Echidna, and a sibling of monsters like Cerberus and the Lernaean Hydra, the chimaera was described differently in The Iliad as orated by Homer as, “a thing of immortal make, not human, lion-fronted and snake behind, a goat in the middle, and snorting out the breath of the terrible flame of bright fire” (Homer, Iliad, 16: 328–329) versus Hesiod's Theogony, “a creature fearful, great, swift-footed and strong, who had three heads, one of a grim-eyed lion; In her hinderpart, a dragon; and in her middle, a goat, breathing forth a fearful blast of blazing fire” (Hesiod, Theogony: 319–325). These descriptions with both their contradictions and their similarities explain why artistic depictions can vary so widely, especially due to the sharing and competition that would arise if both Homer and Hesiod were contemporaries living in Greece around 750 BCE, as is thought by scholars (Griffin, 1986: 88).

Figure 12. Chimera, South Italian red-figure kylix, Apulian red-figure dish, ca. 350-340 BCE, Musée du Louvre (from theoi.com).

Figure 13. Chimera on vase (photo from Athens Archaeological Museum).

Figure 14. Chimera from Arezzo, c. 400 B.C.E. (Etruscan), bronze, 129 cm in length, (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence) [originally part of a group with Bellerophon and Pegasus].

Figure 15. A chimera (1590–1610), attributed to Ligozzi, Jacopo Copyright ©Museo Nacional del Prado

Figure 16. Hellenistic Greek pebble mosaic depicting Bellerophon riding Pegasus while killing the Chimera, c. 300–270 BCE. Archaeological Museum of Rhodes, Greece.

These were not the only authors who wrote on the Chimera. She also makes appearances in Book 1 of the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus, in the Fabulae 57 and 151 by Hyginus, in Books VI: 339 and IX: 648 of the Metamorphoses by Ovid, and as a ship name in Book 5 of the Latin epic poem the Aeneid by Virgil between 29-19 BCE (Nicoll, 1985).

As a reflection of the volcanic land of Mount Chimaera in Turkey and with its/her connection to the God of smithing, the Chimera could have been named for this connection. It's not particularly surprising then that the Greeks gave her the background and powers she had, but did they have to make her a "monster"?

The Sphinx

Maybe the most recognised example of a chimaera, though not always seen as one, is the Sphinx. Though, like the chimaera, there are multiple representations of sphinxes, mostly due to the cross-cultural pollination of the word through the expanding Greek and Roman empires. According to its entry in the 1848 edition of A Dictionary of Greek Biography and Mythology, the Latin word sphinx came from the Ancient Greek Σφίγξ (Sphínx), which seems to derive further from σφίγγω (sphíngō) meaning "to pull tight", "to squeeze", or "to strangle" or from the Egyptian 'she-sep-ankh' šzp-ꜥnḫ, “divine image”, literally "living image" (Smith, 1848). The trouble with the Egyptian translation, however, is that that wasn't the Sphinx's name [as that was Haremakhet from the New Kingdom], but a generic catch-all term like chimaera, and the Greeks misunderstood what they were translating (Zivie-Coche, 2004: 12). The word for 'divine image' works for all statuses, especially when showing the face of a king or god (Zivie-Coche, 2004: 12).

The Gryffon

Figure 22. Alpha Griffon (Dungeons and Dragons 5e v1.3 Monster Manual)

Figure 23. Bronze figure of a gryphon, Roman period (50 – 270 CE) (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden)

Figure 24. "Bronze gryphons from ancient Luristan, Iran (1st millennium BCE) Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin" (photo by Wolfgang Sauber, 2012).

Figure 25. Taxidermy Griffin, Zoological Museum, Copenhagen

Figure 26. A soldier fighting a Griffin ('Alphonso' Psalter, 1284)

Figure 27. Statue of a griffin at St. Mark's Basilica in Venice (Photo by Nino Barbieri, 2004)

Figure 28. Coat of arms of the Gryf (Griffin) dynasty of Pomerania (from c. 1200) and of the modern Zachodniopomorskie Voivodship in Poland

Figure 29. Heraldic guardian griffin at Kasteel de Haar, Netherlands, 1892–1912 (photo by Gebruiker, Ellywa).

Also sometimes known as a hieracosphinx, the gryphon is a mix of a bird, typically an eagle, falcon, or hawk, and a lion. The etymology of the word is Greek in origin, as the name was coined by Herodotus for the hawk-headed sphinxes that he saw in Egypt (Gwynn-Jones 1998). The god Haroeris ("Horus the Elder") was usually depicted as one. The name Hieracosphinx comes from the Greek Ιερακόσφιγξ, itself from ἱέραξ (hierax "hawk") + σφίγξ ("sphinx") (Collins Dictionary) It has like many Chimaera and sphinxes artists and authors, presented a wide variety of attributes, including a horse body (which is already a creature called a hippogryph), no wings, and long ears like belonging to a horse. Another version of the sphinx from Egypt was the ram-headed sphinx which Herodotus called Criosphinx (Ancient Greek: Κριόσφιγξ).

Figure 30. The griffin (Martin Schongauer, 1485 CE)

Figure 31. Restored gryphon fresco in the "Throne Room", Palace of Knossos, Crete (original from Bronze Age)

Figure 32. Bronze gryphon head from Olympia, Greece (7th century BCE). Olympia Museum (photo by Nanosanchez)

These changing forms and ideas of gryphon-like creatures also appear in a variety of other mythological traditions, with views of their contributions being either helpful or harmful. These include:

Anzû

Figure 33. Drawing by L. Gruner - 'Monuments of Nineveh, Second Series' plate 5, London, J. Murray, 1853

From Assyrian mythology, “Ninurta with his thunderbolts in pursuit Anzû who was stealing the Tablet of Destinies from Enlil's sanctuary” (Layard, 1853). The lion-bird, alternatively called Zû or Imdugud (Sumerian:𒀭𒅎𒂂), is either the son of Siris or of the "pure waters of the Apsu", depending on the version (Alster, 1991; Penglase, 2003; Jacobsen, 1989).

The Ziz

From Hebrew Mythology - An archetypal monster thought to be so big he could block the sun. In the art, he is shown with the Behemoth (land) and the Leviathan (sea) (Figure ). According to parts of the Bible after judgement day “Ziz is a delicacy to be served to the pious at the end of time, to compensate them for the privations which abstaining from the unclean fowls imposed upon them. [...]” (Barnstone, 2005; Ginzberg & Cohen, 1913).

A Chinese Pixiu (貔貅; píxiū)

A hybrid creature of either prosperity and wealth or the warding away of evil spirits, depending on which gender they were, which one could tell by the antlers. The former were male, called Tiān lù (天祿) and the latter, Bìxié (辟邪), were female (Bates, 2008: 48-9). The females had the head of a Chinese dragon, the body of a lion and a pair of feathered wings, at the tomb of Emperor Wu of Southern Qi 南齊武帝 (Xiāo zé 蕭賾) in Danyang (near Nanjing, China).

Simurgh

According to the epic Shahnameh (Book of Kings) by Ferdowsi between 988-1010 CE, the Simurgh (or in Persian senmurw), of Zoroastrian mythology from Ancient Persia [present day Iran] is an inherently benevolent creature. Sufi poetry from around the 12th c. CE, and Kurdish folklore, purifies and blesses the land with fertility (Cirlot, 2002: 253; Schmidt, 2003). The Simurgh symbolized unity and connected Earth and Sky. Residing in the ‘Tree of Knowledge,’ her flight shook the tree, scattering seeds from every plant, aiding humanity. Eventually, she made her nest in the sacred Alburz mountain, which was inaccessible to humans. She has the head of a snarling dog, the paws of a lion and the tail of a peacock. Like the other chimaera descriptions can vary; showing her with a human head, or closer to a full bird (Schmidt, 2003).

Figure 41. Sassanid silver plate, simurgh (Sēnmurw), 7th or 8th CE gilded plate (Persian Empire collection of the British Museum).

Manticore

The word Manticore from the Early-Middle Persian: Mardyakhor or Martikhwar, meaning “man-eater” according to Pausanias in his Description of Greece, is the name of an Iranian legendary hybrid creature (Pausanias 9.21.4). It was described by a Greek physician named Ctesias in his book Indica (“India”), in which he wrote about the natural history of the area from his time at the Persian court of King Artaxerxes II in 400 BCE. Aelian, a Roman author who lived around 200 years later, wrote that the manticore was a "wild beast" with ‘the head of a man on a body as shaggy and large as a lion with lion's feet and claws, and a tail of a scorpion’. Ctesias asserts that while they are young the manticores don't have stingers, so that's when they are hunted by local people. This is so they can killed and the tail crushed without releasing the "evil" from their stingers, producing an evil crop (Aelian, Characteristics of Animals, 4.21).

Later writers and philosophers, such as Pausanias (110-180 CE) [in his Description of Greece], Aristotle, Pliny the Elder [in Naturalis Historia 8:30, c. 77 CE], and Greek writer Flavius Philostratus (170–247 CE) [in The Life of Apollonius of Tyana] kept the ideas going for centuries of stories, describing the being as anything from a regular man-eating tiger to the hybrid beastly creature described above (Christensen 2003, Pausanias, Description of Greece, 9.21.4). Inspired by the authors of ancient times, mediaeval authors and scholars continued the tradition of including the manticore in bestiaries, sometimes depicting it as a tiger, sometimes with tusks and monkey-like feet, maybe a huge scorpion tale with added quills, and still sometimes with a woman's head (Dennys 1975: 114–7, Topsell 1607, Holme 1688, Moffit 1996).

Figure 41. Manticore from Dungeons and Dragons Monster Manual 5th edition.

Figure 42. The Manticore, or Martigora, described by Pliny and Aristotle, has a human face, grey eyes, a red body, a scorpion-like tail, lion-sized stature, lion's paws, three rows of teeth, and a taste for human flesh (Jonstonus, Joannes 1678).

Figure 43. Edward Topsell's The History of Four-footed Beasts (1658) (Kleber, et. al, 2017).

Figure 44. Ketterij: engraving of the Heresy represented as a goddess accompanied by a manticore, copper engraving by Antonius Eisenhoit (1589).

Figure 45. Artist unknown, Manticore in an illustration from the Rochester Bestiary detail, 12th century (c. 1230–1240). The British Library, London, Britain.

Figure 46. Al Buraq Deccan painting This image mixes visual traditions from Central Asia, Turkey, and Iran, but the main focus is the elephant from India and gently protecting a scared deer (18 AD).

Wider Audience for Sphinxes

Figure 48. The male purushamriga is situated at the east entrance of the Shri Shiva Nataraja temple in Chidambaram, India (photo by Raja Deekshitar).

Figure 49. A Burmese depiction of the Manussiha (by Temple, Richard Carnac, Sir - The Thirty-Seven Nats, from Southeast Asia Digital Library).

So with a greatly expanded definition of the sphinx, it is tricky to know which of the Hellenized versions of the 'creature' came first (not speaking to the worldwide original story). In the increasingly connected Mediterranean world, was it the Greek translation of the Egyptian word for the statue or the Sphinx in the story of Oedipus Rex, within which the female-headed version blocked the entrance to seven-gated Thebes with her famous riddle? In Cairo (not 100-gated Thebes) the male-headed version, 'androsphinx' was recarved from what some scholars think was the head of a lioness to the head of Pharaoh Khafre around 2550 BCE (Cassella, 2018: 10). Evidence seems to point in multiple directions, and is part of ongoing discussions about the sphinx and subsequent topics, which are expansive enough to fill multiple books. In the Egyptian versions, sphinxes are protectors, killers, maybe, but as any mother lioness would guard her young, not unlike the origin story of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet, but not the mysterious 'gynosphinx' (female-headed) that killed anyone who couldn't solve her riddle.

Figure 50. Persian Sphinxes. Palace of Darius I, Susa, Persian Empire. C. 500 BC. Glazed brick sphinxes in one of the friezes of the palace. The relief shows a pair of winged lions with bearded human heads. The winged disc of Ahura-Mazda hovers above them. Traditional Persian iconography.

Figure 51. Ancient Greek sphinx from the Temple of Apollo Delphi (570-560 BCE) (Ricardo André Frantz, 2006).

Figure 52. Wooden ceremonial shield with the king as sphinx trampling on Nubian enemies. From King Tutankhamun's tomb (c. 1334-1325 BCE).

Even while the whole creature was changing, one big aspect remained generally consistent, that it was a monster. But, that wasn't the case in all of the world. Like in Egypt, some of the myths coming from India and South and Southeastern Asia regard the creatures as, depending on the place, avatars for gods, guardians, and/or wards against evil, even though they were described and painted as, and called beasts.

Variety of Gods

Carving of Sobek on the left side at the Temple of Sobek

Carving of Horus in the middle standing on a boar/pig in front of Hathor at the Temple of Horus

Carving of Hathor with cow ears at the Temple of Isis

(Photos are all my own from Egypt, 2016).

Egyptian Gods and Goddesses are widely known for being depicted with animal heads; Ra as the eagle, Horus the falcon, Anubis the jackal, Sobek the crocodile, Hathor as a cow, etc. These deities filled the pantheon with good and evil, Osiris was good, and Set was bad, but that was never contingent upon which animals were represented. The perfect example is the snake, represented by both the Goddess Wadjet, protector of the Pharaoh, and the God Apophis, who tries to eat Ra every night and is connected to darkness, thunder, earthquakes, and chaos.

But Egypt wasn't the only ancient civilization that put the heads of kings and gods on animal bodies or even the other way around. In ancient Assyria, for example, bas-reliefs of shedu bulls with the crowned bearded heads of kings guarded the entrances of temples.

Figure 53. The Assyrian Lamassu at the Oriental Institute Museum at the University of Chicago. Khorsabad, entrance to the throne room Neo-Assyrian Period, ca. 721-705 B.C. This 40-ton statue was one of two flanking the entrance to the throne room of King Sargon II. A protective spirit known as a lamassu, it is shown as a composite being with the head of a human, the body and ears of a bull, and the wings of a bird. When viewed from the side, the creature appears to be walking; when viewed from the front, to be standing still. Thus it is represented with five, rather than four legs. (Trjames - Own work)

Narasimha

India uses the Sanskrit purushamriga meaning "man-beast", naravirala meaning "man-cat", or in Tamil purushamirugam also meaning "man-beast". While in Sri Lanka Narasimha in Sanskrit is "man-lion" it is manusiha in Myanmar or manuthiha in Pali. In Thailand and Pali, Norasingh also means "man-lion", this came from a variation of the Sanskrit "Narasimha", or was called the thep Nora Singh meaning "man-lion deity", or Nora nair (Deekshitar 2004: 34-41, Kosambi 2002: 459). The Narasimha ("man-lion") is described as an incarnation (Avatar) of Vishnu within the Puranic texts of Hinduism who takes the form of a half-man/half-Asiatic lion, having a human torso and lower body, but with a lion-like face and claws.

Figure 54. Narasimha, Chola period, 12th -13th century, Tamil Nadu. From Musée Guimet, Paris. (Photo by Vassil).

Figure 55. Vishnu and his avatars (Vaikuntha Chaturmurti): Vishnu himself or Vasudeva-Krishna in human form, Narasimha as a lion, Varaha as a boar. Art of Mathura, mid-5th century CE. Boston Museum. (Schmid, 1997). (Photo by Neil Noland).

Figure 56. Lion-headed God, fourth Avatar of Vishnu

Garuda

A Hindu deity who is primarily depicted as the mount (vahana) of the Hindu god Vishnu. This divine creature is mentioned in the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain faiths (Buswell & Lopez 2013, Dalal 2010: 145, Von Glasenapp 1999: 532). Garuda is described as the king of the birds (Williams 2008, Rao 1985). He is shown either in a zoomorphic form (a giant bird with partially open wings) or an anthropomorphic form (a man with wings and other ornithic features).

Figure 57. Garuda secures Amrita by defeating the Daitya. Photo from Hyougushi/Hideyuki KAMON from the National Museum in Delhi, India

Figure 58. "Relief depicting a portable Garuda pillar, one of the oldest images of Garuda, Bharhut, 100 BCE" from Penang, Malaysia (Gupta, The Roots of Indian Art, 1980, p.29).

Figure 59. The Balinese wooden statue of Wishnu riding Garuda as his mount. Purna Bhakti Pertiwi Museum, Taman Mini Indonesia Indah, Jakarta. (photo by Gunawan Kartapranata).

Figure 60. Garuda (Khmer: គ្រុឌ, Krŭd) in Koh Ker style. Made of sandstone, this statue is from the first half of tenth century, (Angkor period). On display at the National Museum of Cambodia.

Figure 61. National Emblem of Thailand, depicting a dancing Garuda with outstretched wings. The Garuda symbolizes the government and people of Thailand, as Lord Vishnu symbolizes the King of Thailand.

So many of these are not only in stories of their history from their separate lives from humans, but in the ways they would continue to impact the world. In the various mythos from around the world in which humans are rarely directly involved the Gods and Goddesses are shown as protectors and balancers of nature and the universe at large. When they are depicted in statues, in all their glory, the people may have wanted to recognize the connection that humans have with nature, by combining humans with animals.

*As an aside: A question I don't have an answer to is; why were stories from Ancient Greek and Roman mythology which link to the Western Medieval traditions far more against the mixing of creatures’ forms and still being benevolent, while civilizations in Egypt, the Near East, and many Far Eastern cultures had much less issue with chimaera not being monsters? Could it have to do with an early embankment in these particular cultures against the natural world?

More Worldwide Mythical Chimera

There are far too many chimerical creatures scattered around the world to cover them all, so like in the previous post they'll be named with links included and pictures.

The Beast in Christianity eschatology

The Beast of the Sea (Tapestry of the Apocalypse)

Dābbat al-Arḍ (Beast of the Earth) in Islamic eschatology

17th-century Mughal miniature of the Beast

Lamassu, Assyrian deity, bull/lion-eagle-human hybrid

Lamassu from Dur-Sharrukin. University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Syrian limestone Neo-Assyrian Period, c. 721–705 BCE (Photo by Trjames, 2020).

Lamma, Assyrian deity, female winged deity

Lamma Goddess, Iraq, Isin-Larsa period, 2000-1800 BC, bronze, baked clay - Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago

Nue, Japanese legendary creature

Pegasus, the winged stallion in Greek mythology

“Yes, there he sat, on the back of the winged horse!” by Mary Hamilton Frye - Mabie, Hamilton Wright (Ed.): “Myths Every Child Should Know” (1914).

Parthian-era bronze plate depicting Pegasus (Pegazin Persian), excavated in Masjed Soleyman, Khūzestān, Iran.

Gopaitioshah – The Persian Gopat or Gopaitioshah is another creature that is similar to the Sphinx, being a winged bull or lion with a human face.("Dadestan-i Denig, Question 90, Paragraph 4"; "Menog-i Khrad, Chapter 62"). The Gopat have been represented in the ancient art of Iran since the late second millennium BCE and was a common symbol for dominant royal power in ancient Iran. Found in the texts of the Bundahishn, the Dadestan-i Denig, the Menog-i Khrad, as well as in collections of tales, such as the Matikan-e yusht faryan and in its Islamic replication, the Marzubannama (Taheri, 2013).

Löwenmensch figurine "Lion Man"

The Löwenmensch figurine after restoration in 2013 (Photo by Dagmar Hollmann)

The 32,000-year-old Aurignacian Löwenmensch figurine, also known as "lion-human" is the oldest known anthropomorphic statue, discovered in the Hohlenstein-Stadel, a German cave in 1939.("New Life for the Lion Man - Archaeology Magazine Archive". <archive.archaeology.org>).

For a fuller list of Hybrid Creatures.

Origins

The Medieval Latin word chimera, from Latin Chimaera, was Latinized from the Ancient Greek 'χίμαιρα' khimaira, or Chímaira, which literally meant "she-goat". As opposed to a "male goat" 'χίμαρος' khímaros " (“chimera; chimaera, n.”, in OED Online , Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1889). This direct connection to the etymology in the Greek creature name does bring up the question, of which came first; the gender of a mythological creature or the word? While there isn't a definitive way to say for sure scholars have looked through other etymological links to find hints.

Neo-Hittite Chimera from Carchemish also spelt Karkemish (Turkish: Karkamış), at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations (850-750 BCE). The tablet in the photo below shows a Chimera with a human head with "a hooked nose pointing to a Luvian or Hittite ethnic origin" over a lion's head (Figure 62). This relief was from Herald's wall, Carchemish in Late Hittite style under Aramaean influence and is now housed in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, in Ankara, Turkey.

Figure 62. Chimaera relief from Carchemish

This transfer of myths between groups is sometimes believed to be the origin of the Greek version. While we don't have specific dates of when myths were originally told, one of the recorded stories of Bellerophon slaying the chimaera is in the Theogony by Hesiod who lived sometime between 750-650 BCE (West, 1966: 40; Griffin, 1986: 88). An older appearance of the chimera is made in Book 16 of the Iliad which thought to have been written in the 8th century (800-700) BCE (Vidal-Naquet, 2000: 19). Around the same time, perhaps around the length of a lifetime after the Hittite version was sculpted. Of course, this has no bearing on oral traditions, if the creatures were transplanted via spoken stories, like Homer would have done, tracing the first mention is next to impossible.

The mountainous region in ancient Lycia, more specifically Mount Chimaera, is thought to be the modern area Yanartaş in Turkey, where some scholars think that the gas and fires were the origin of the entire Greek Chimera myth when described by Pliny the Elder [4.1] after he was originally told the story (Healy, 2004; 'Chimera', 1854). This same area was named in the speech made by Iobates as the monster's home (Barth, 2001). Possibly due to the dozens of methane gas vents in the ground, this region also houses a Temple of Hephaestus, about 3 km away from Çıralı, near ancient Olympos, Lycia. Another subsequent link could be found because of the town/region of Himarë, in Southern Albania has a substantial Chaonian population [Ancient Greeks] that was originally called Χίμαιρα, Chimaira, or Chimaera, which can explain the name Himara, even if it sounds a bit different today (Hansen, 2005; Liddell, & Scott, 1940; Smith, ed. [1854–1857]). Due to the original myth taking place in Lycia, it is likely that the first area could be one of the story’s originators while the latter shared similarities and was thus named for the pre-existing myth.

Other than from the etymological roots, why do chimaeras even exist? In the case of the Greek gryphon, some scholars think that they were based on the fossilized remains of dinosaurs, much like the idea of dragons. On gryphons, folklorists and historians write that it was specifically from the seventh century BCE on that the Greeks may have been influenced in part by beaked dinosaurs such as Protoceratops and Psittacosaurus, which would have been seen on the way to gold deposits that were found by nomadic prospectors of ancient Scythia in Central Asia and believed to have been assumed to be a mixture of a bird and a mammal (Figure 63)(Mayor, 1994; Mayor, 2011; BBC, 2011). This hypothesis has been contested by Paleontologist Mark P. Witton, who was referenced in the previous bestiary article, pointing out that this hypothesis ignores older depictions of griffons from a variety of Eastern and Near Eastern countries before the Greeks ever knew of the existence of these fossils Witton, 2016). He also argues that the Greek versions of griffons were based on living creatures because the anatomies between the fossils and the mythical versions don't match up (Witton, 2016).

But as for the mere existence of chimaera, an Ancient Studies master's thesis from Liane at Stellenbosch University concluded "that hybrid monsters, as manifestations of the internal dichotomy of man and the tenuous relationship between order and chaos, played a critical role in the personal and communal definition of man in ancient Greece" after examining the myths of the Minotaur, centaurs, etc. (Posthumus, L. 2011).

"Recent" Chimera

"19th c. print of a Chimera-like beast, created to parody various religious denominations" (Library of Congress).

Original Drawing of Cthulhu (Lovecraft, H.P. 1934).

Cthulhu (A. Wallin)

Gotland Sheep Chimera (own work, 2015))

All the animal tiles [5-7](Photos are own work, taken at a street fair in Portland, OR, 2019 by @Whatifcreations).

"He has the head structure and horns of a buffalo, the arms and body of a bear, the eyebrows of a gorilla, the jaws, teeth, and mane of a lion, the tusks of a wild boar and the legs and tail of a wolf. He also bears resemblance to mythical monsters like the Minotaur or a werewolf." (All rights belong to Disney, 1991).

Quimera: The Gorgeously Fluffy Chimera Cat (Cole & Marmalade)

*Fiction for fun - My favorite would be an otterpus.*

*Never mess with Cthuthlu or any of the Elder Gods, they aren't good or bad, they just don't care.

As has been already shown D&D, Pathfinder, and RPGs in the same vein contain hybrid creatures (chimaera) from mythology and add new twists on old versions. With the update of Lovecraftian the base into worldbuilding, there are even more "monsters" to fight. But no one says a player group has to fight, if roleplaying games are about anything, they are about finding creative solutions to different situations. The Beast from La Belle et la Bête did appear frightening and ugly, but incredibly well-mannered even from the beginning, which they altered a bit for the Disney version. But, the Beauty and the Beast story is closer to Eros and Psyche, so I won't be diving into that, although the 1740 French fairy tale and later versions are examples of something that appears monstrous turning out friendly. When implemented in a game the bonus comes from, other than making a friend out of terrifying creatures may give protection and help when needed, but it throws the GM (and that's fun).

After centuries of stories and illustrations, people wanted some proof, this is roughly when people like P.T. Barnum stepped in. An earlier example of a creature that was thought a hoax upon description was the platypus. While described by David Collins in 1797 with an illustration sent back to England it took years, 90 for some people, to finally accept the truth, though for scientists/naturalists like George Shaw, the evidence was right in front of him (Zarrelli, 2016). The platypus, however despite its appearance, is not a genetic chimaera because it's not a mix of different species, it just looks like it could have been. Especially because the description called it a "duck mole".

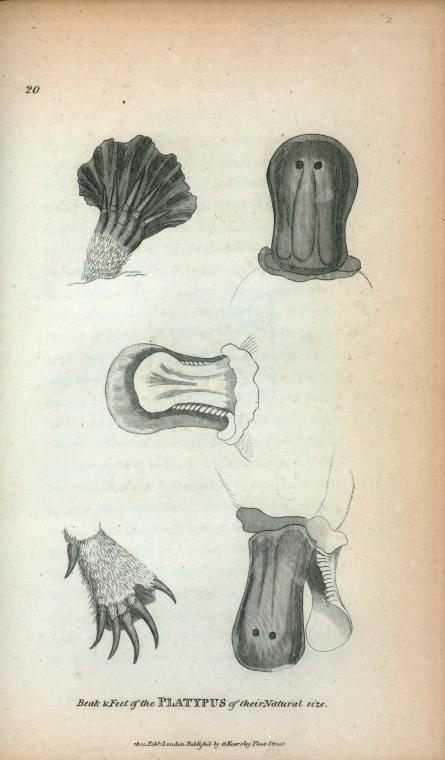

Figure 64. "George Shaw’s depiction of a duck-billed platypus from 1809." (Zarrelli, 2016; Photo: New York Public Library)

Figure 65. "George Shaw’s illustration of the beak and feet of the platypus." (Zarrelli, 2016; Photo: New York Public Library).

Figure 66. "A platypus depicted as a “duck mole” from the 1880 title Johnson’s Household Book of Nature." (Zarrelli, 2016; Photo: Biodiversity Heritage Library/CC BY 2.0).

Less than 50 years later (1840s onwards) P.T. Barnum was billing both, these innocent monotremes and true hoaxes, like the Feejee Mermaid, as "oddities" and "curiosities". Of course, we now know that these are hoaxes. The mermaid, the one paraded around by Barnum, could have been made as a joke on 'tourists' by Japanese fishermen (Levi, 1977). What is not the worst thing Barnum had brought into the world, but is still really horrible is that people can and seem to still buy these "Feejee mermaids" online, talk about perpetuating bad habits for the rest of humanity.

An 1842 advertisement for P.T Barnum’s “Feejee Mermaid”, and “the Duck-billed Platypus, the connecting link between the bird and beast” (Photo: Public Domain).

An illustration of P.T. Barnum's Feejee Mermaid. (Image credit: Public domain).

"A papier-mâché mermaid from the same Moses Kimball collection that once included the Feejee Mermaid exhibited by P. T. Barnum. The collection met with fire in 1899. Exhibit from the Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA." ("Feejee Mermaid". Peabody Museum, 2019).

Conclusion

Genetics change, stories are told, new discoveries are made. How we react to new things and experiences can help us see a way into the future. Many creatures, mythical or otherwise, can be beastly, adorable, or even both. The most important thing is to read the behaviours that the smartest heroes seem to do in their myths. If we take all these chimeras as real beings, Gods, magical, etc. we can see that they tend to act like a person in the same situation. The myth of Bellerophon is a story of the archetypal hero, brought down by his hubris (Szachnowska-Olesiejuk, 2010). His first enemy was a chimaera, and so was (technically) the friend he had to make to succeed in his task, though they had different names. Mythology, folklore, and changing language reflect the atmosphere of the culture at the time, and will most certainly evolve over the centuries. The name Chimera turned into a vast definition covering Gods and mythological creatures, scientific naturalistic studies, more advanced genetic works, and even computer language.

Chimera are seen as monsters, friends, protectors, Gods, and even chaos incarnate. What I hope that we can all learn is that we can't judge a book by its cover. The biggest change seems to be that Chimera has gone from being illusionary to being stories to reality. All it took was a change of perception.

Additional Information:

Most links are in the text, but...

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Miscellaneous Myths: The Tarasque (2018)- Red even says "Chimerical mashup..." within the 1st minute and 5 seconds in.

Judgment of the Humanness/Animality of Mythological Hybrid (Part-Human, Part-Animal) Figures

Man and Beast: The Hybrid in Early Chinese Art and Literature

The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses by George Hart

More etymological root diving, the 'chim-' in chimaera is often linked to *gheim- meaning "winter", also appearing in the name of the Himalayas, and could be traced back to the Sanskrit word heman meaning "in winter". Don't see how or even if this connects to the rest of our narrative, but just pointing out how weird languages are.

Citations:

Alster, B. (1991). Contributions to the Sumerian lexicon. Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale, 85(1): 1-11.

Bates, Roy (2008). "Chapter 7".29 Chinese Mysteries. Beijing, China: TuDragon Books Ltd.: 48-49.

Barnstone, Willis (2005).The Other Bible. Harper Collins. 23-4. ISBN978-0-06-081598-1.

Barth, J. (2001).Chimera. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

BBC. (2011). Dinosaurs, Myths and Monsters [TV programme]. 4.

Becchio, Bruno; Schadé, Johannes P. (2006). Encyclopedia of World Religions. Foreign Media Group. ISBN9781601360007.

Buswell, R. E., & Lopez, D. S. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. 314–315.

Cassella, A. (2018). Exploring the Sphinx and the Great Pyramid through the logos heuristics. Int'l J. Soc. Sci. Stud., 6. 10.

Chatterjee, S. (1991). "Cranial anatomy and relationships of a new Triassic bird from Texas."Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 332: 277-342.

Chiappe, L. (1995). "The first 85 million years of avian evolution". Nature. 391 (6555): 147–152.

'Chimaera' in William Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, (1854).

'Chimaira'. Liddell, Henry G. & Scott, Robert. (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus. Oxford. Clarendon Press.

Christensen, A. P. (2003).The Panathenaic Stadium: its history over the centuries. Historical and Ethnological Society of Greece.

Cirlot, J. E. (2002). A Dictionary of Symbols. Mineola, NY.: 253.

Dalal, R. (2010). Hinduism: An alphabetical guide. Penguin Books India. 145.

Deekshitar, R. (2004). Discovering the Anthropomorphic Lion in Indian Art. Mårg. A Magazine of the Arts, 55(4), 34-41.

"Definition of 'hieracosphinx'". www.collinsdictionary.com.

Ginzberg, Louis & Cohen, Boaz (1913). Bible times and characters from the creation to Jacob. Jewish Publication Society of America.

Griffin, Jasper. (1986). "Greek Myth and Hesiod", J. Boardman, J. Griffin and O. Murray (eds), The Oxford History of the Classical World, Oxford University Press. 88.

Gwynn-Jones, P. L. (1998). The Art of Heraldry: Origins, Symbols and Designs. Barnes and Noble.

Hansen, Mogens H. (2005). An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis: An Investigation Conducted by The Copenhagen Polis Centre for the Danish National Research Foundation: 340.

Healy, John F. (2004). Pliny the Elder: Natural History: A Selection. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044413-1.

Holme, Randle (1688).The Academy of Armorie and Blazon. Chester. p. 212.; quoted in Dennys 1975, p. 115.

Jacobsen, T. (1989). "God or Worshipper". in Holland, T.H. (ed.), Studies In Ancient Oriental Civilization no. 47. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: 125-130.

Kleber, Da & Vieira & Luiz, Washington & Alves, Rômulo & Alves, Nóbrega. (2017). Imaginary Zoology: Mysterious Fauna in the Reports of Ancient Travelers and Chroniclers. 10.1016/B978-0-12-809913-1.00005-3.

Kosambi, K. D. D., Kosambi, D. D., K. D. D. (2002). Combined methods in Indology and other writings. India: Oxford University Press.

Levi, S. (1977). P. T. Barnum and the Feejee Mermaid.Western Folklore, 36(2), 149-154. doi:10.2307/1498966

Loewe, M. (1978). Man and Beast: The Hybrid in Early Chinese Art and Literature.Numen,25(2), 97-117. doi:10.2307/3269782

Mayor, Adrienne (1994). "Guardians of The Gold". Archaeology Magazine. 47(6): 53–59. JSTOR41766590.

Mayor, A. (2011). The first fossil hunters: dinosaurs, mammoths, and myth in Greek and Roman times. Princeton University Press.

Moffitt, John F. (1996). “An Exemplary Humanist Hybrid: Vasari's "Fraude" with Reference to Bronzino's "Sphinx” ”. Renaissance Quarterly.49(2): 303–333. doi:10.2307/2863160. JSTOR 2863160.

Harvey Nash (1974) Judgment of the Humanness/Animality of Mythological Hybrid (Part-Human, Part-Animal) Figures, The Journal of Social Psychology, 92:1, 91-102, DOI: 10.1080/00224545.1974.9923076

Nicoll., W.S.M. (1985). "Chasing Chimaeras". The Classical Quarterly New Series, 35.1: 134–139.

Noyer, Jérémie (October 11, 2010)."Beauty And The Beast: Glen Keane on discovering the beauty in The Beast".Animated Views. Animated Views.

Pausanias (1918). Description of Greece. Vol. 1. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-434-99093-1.

Penglase, Charles. (4 October 2003). Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod. Taylor & Francis. ISBN978-0-203-44391-0.

Philostratus, F. (1809).The life of Apollonius of Tyana: Translated from the Greek of Philostratus. Vol. I, Book III. Chapter XLV: 327–329. Payne.

Posthumus, L. (2011).Hybrid monsters in the Classical World: the nature and function of hybrid monsters in Greek mythology, literature and art(Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch).

Rao, T. G. (1985). Elements of Hindu iconography (Vol. 1). Motilal Banarsidass Publishe.

Rebold B., Janetta. (1997). Holy Terrors: Gargoyles on Medieval Buildings. New York: Abbeville Press. pp. 8–10. ISBN0-7892-0182-8.

Schmid, Charlotte (1997).Les Vaikuṇṭha gupta de Mathura : Viṣṇu ou Kṛṣṇa?. pp. 60–88.

Schmidt, Hanns-Peter (2003). "Simorg". Encyclopedia Iranica. Costa Mesa: Mazda Pub.

Schrager, Norm (October 8, 2010)."Building a Beast: Interview with Disney Animator Glen Keane". Meet In The Lobby. Meet In The Lobby.

Segalen, V., Joly-Segalen, A., & Elisseeff, V. (1972).Chine: la grande statuaire. Flammarion. Fig. 25: 25.

Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Chimaera". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

Smith, William ed. (1848). "Sphinx". A Dictionary of Greek Biography and Mythology, London: John Murray.

Szachnowska-Olesiejuk, Z. (2010). Myth regained: The postmodern depiction of myths in John Barth’s Chimera. BEYOND PHILOLOGY, 175.

Taheri, Sadreddin (2013)."Gopat and Shirdal in the Near East". Tehran: Honarhay-e Ziba Journal, Vol. 17, No. 4.

Topsell, Edward (1607).The Historie of Foure-footed Beasts. London: 442.

Vidal-Naquet, Pierre (2000). Le monde d'Homère(The World of Homer), Perrin. pp. 19.

Von Glasenapp, H. (1999). Jainism: An Indian religion of salvation (Vol. 14). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 532.

West, M. L. (1966). Hesiod: Theogony, Oxford University Press: 40.

Williams, G. M. (2008). Handbook of Hindu mythology. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 21, 24, 63, 138.

Witton, M. (2016). Why Protoceratops almost certainly wasn't the inspiration for the griffin legend. https://markwitton-com.blogspot.com/2016/04/why-protoceratops-almost-certainly.html

Zarrelli, N. (2016).Why 19th-Century Naturalists Didn't Believe in the Platypus. Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2 June 2020, from https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/why-19th-century-naturalists-didnt-believe-in-the-platypus.

Zhou, Z (2004). "The origin and early evolution of birds: discoveries, disputes, and perspectives from fossil evidence". Naturwissenschaften. 91(10): 455–471.

Zivie-Coche, C. (2004). Sphinx: history of a monument. Cornell University Press.

![Figure 21. Photo of two kinds of sphinx, king-headed in the foreground and ram-headed versions [criosphinx] lining the background in the Temple of Karnak (Whitehouse 2015).](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6598c864ea0f89700c0e4e59/1723780575136-S7SME0PYDBR5EZ596ZYZ/IMAG8146.jpg)