Death of Coyolxāuhqui

In 1978, workers at an electric company accidentally discovered a large stone relief in front of a multi-stage temple under the streets of Mexico City (Figure 1). The Mexica (Aztecs) or Culhua-Mexica are of Nahua ethnicity and have multiple lunar deities. The main lunar goddess depicted on the stone is named Coyolxāuhqui (Nahuatl pronunciation: Koy-ol-shauw-kee) meaning something close to "Women painted/adorned with copper bells" or “Bells-on-her-face” and is immortalized in a humiliating form on the monolith (Milbrath 1997: 185, Townsend 2009: 57, Kilroy-Ewbank 2015).

Figure 1. View of the Templo Mayor excavations today in the center of what is now Mexico City (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Visitors to Mexico City, as it was built directly on top of Tenochtitlan, can still feel the intimidation factor from where the stone at the base of Templo Mayor once lay while waiting in line to get into the National Museum (Figures 2-5). The monolith was originally placed in its position to show the power of the Mexica Empire and how they used human life from other places. It also made clear what they found most important.

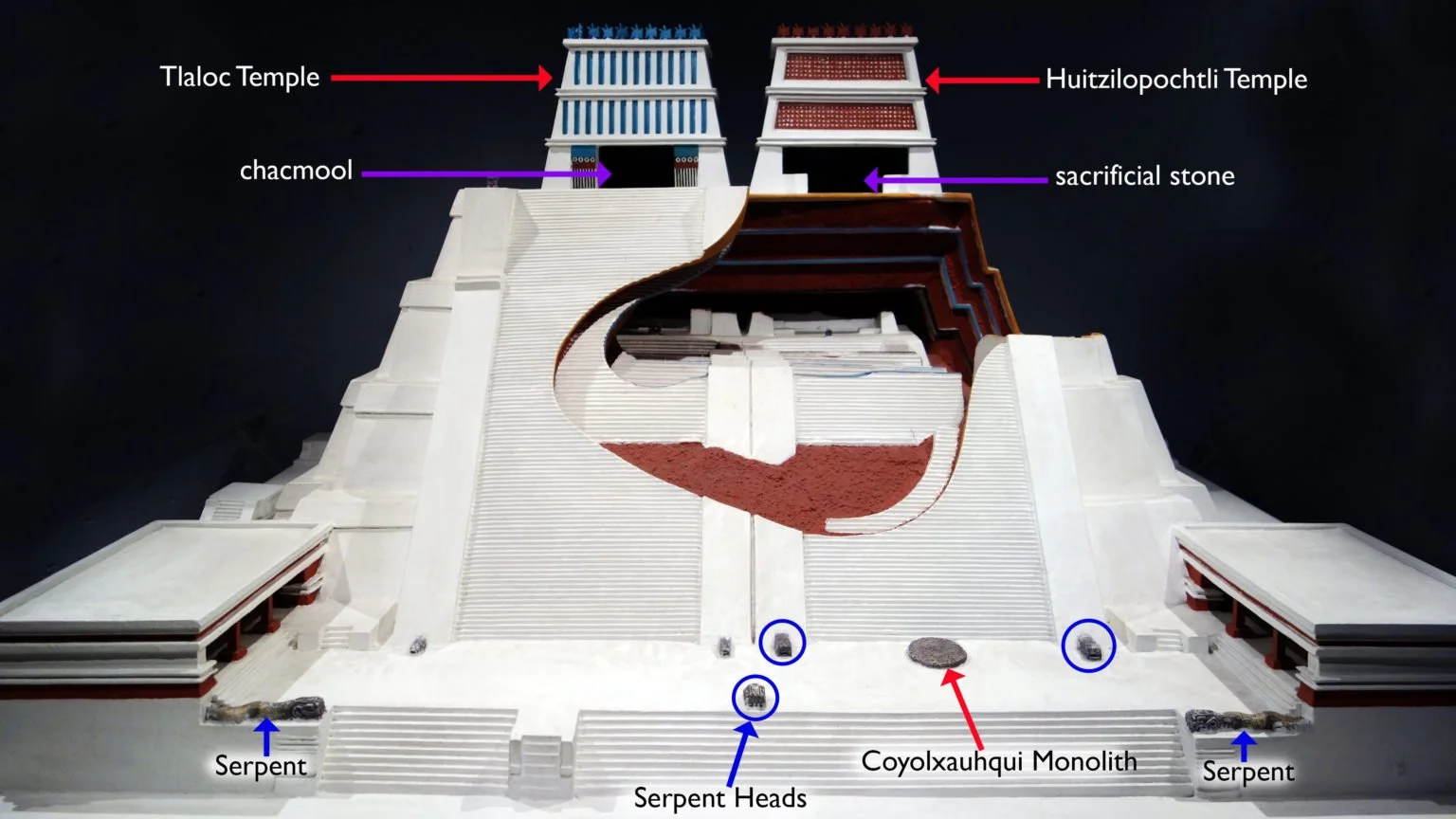

Figure 6. Templo Mayor (reconstruction), Tenochtitlan, 1375–1520 C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This major sculpture depicts the aftermath of her sibling’s birth in mythology in front of the Temple of the Huītzilōpōchtli side of the Templo Mayor (main temple), or Huēyi Teōcalli in Nahuatl, in Tenochtitlan (Figure 6) (Kilroy-Ewbank 2015, Townsend 2009: 149).

Figure 7. The founding of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan; An eagle representing Huitzilopochtli, which exhales the atl-tlachinolli (war symbol), is perched on a nopal cactus. Teocalli of the Sacred War, sculpted in 1325.

According to tradition, the Templo Mayor was erected on the exact spot where Aztlán pilgrims discovered the sacred cactus growing on a stone, on which an eagle sat with its wings opened to the sun, eating a serpent (Figure 7) (Solis & Gallegos 2000). This was also the promise of a home that was immortalized on the Mexican flag. Despite its simple construction with mud and wood, this initial monument dedicated to Huītzilōpōchtli represented the start of what would later become one of the most famous ceremonial buildings of its time. Through the years, the rulers of Mexico-Tenochtitlan would build a new construction stage on that pyramid, and although the works generally only consisted of attaching slopes and renewing stairs, the power of their ruler and their veneration of the god caused the pyramids to keep growing larger and eventually rose to ninety feet tall and was fully stuccoed (Kilroy-Ewbank 2015). Other gods were also honored by the Nahoa for preserving harmony, balancing nature's powers, and supporting plant growth for human sustenance. The Templo Mayor, therefore had twin temples devoted to Tlaloc and Huītzilōpōchtli. The former, Tlaloc, was the deity connected with water, rain, and agricultural productivity and the latter was the god of the Sun, warfare, and sacrifice as the patron god of Tenochtitlan whose name translates to “Left-Handed Hummingbird” or “Hummingbird of the South” on the basis that Mexica cosmology associated the south with the left-hand side of the body (Britannica 2021). Together they represented the Mexica notion of atl-tlachinolli, or scorched water, which represented warfare and the primary way of attaining power and wealth in the Mexica culture at the time (Kilroy-Ewbank 2015). Humans were sacrificed atop this temple, and their remains were dismembered and thrown down the stairs to the base, like in the tale of Huītzilōpōchtli’s birth and Coatepec (‘Snake Mountain’, also spelt Coatepetl).

The stone, carved in c. 1473 CE during the reign of Axayacatl, is a high-relief monolith carved on a single stone 3.4 meters (almost 11 ft) in diameter (Townsend, 2009). Due to her naked depiction at least half of my 15-person archaeological study abroad class, including me, started calling her ‘Tits Magee’ (Figure 8). Not the nicest thing, we were being pretty dumb and culturally insensitive. However, in making fun of Coyolxāuhqui we were unknowingly taking part in the centuries-old tradition because, for the Mexica, nakedness was considered a form of humiliation and defeat (Kilroy-Ewbank 2015).

Mythology

Figure 8. Coyolxauhqui Stone, ca. 1469 Museo del Templo Mayor, Mexico City.

The mythology is amazing, as there are many various versions of the story, so I'll share the first one that I heard back in 2014, and then some variations. Just know that while researching, almost everything I read differed in one way or another.

So, long, mixed-up story short:

Coyolxāuhqui's mother was the priestess Cōātlīcue (“Skirt of Serpents”), also known as Tēteoh īnnān (“mother of the deities”), the goddess of life and death, rebirth, and fertility. One day, while Cōātlīcue was sweeping in a temple a ball of feathers fluttered from the heavens and landed on her breast. This caused her to become pregnant and her belly swelled. She later returned home to her daughter and 400 sons, the Centzón Huitznahuas (the Four Hundred Southern Stars), and Coyolxāuhqui saw her mother's condition and became enraged as her mother had dishonored her entire family by getting pregnant. Coyolxāuhqui pulled her brothers aside and plotted to murder their mother. Unfortunately, she must not have pulled them far enough to the side because Cōātlīcue overheard everything, but she didn't panic long because she had a baby Huītzilōpōchtli growing in her uterus who told her that she shouldn't worry, he would protect her.

That night, the 400 brothers dressed in their warrior garb and followed Coyolxāuhqui to kill their mother in her sleep. Because the group had been found out, both Cōātlīcue and Huītzilōpōchtli were prepared for the attack. In an instant, Huītzilōpōchtli burst out of his mother's body fully grown and armed and started cutting down all of his brothers, without fully killing them, before turning his axe towards his sister. With no chance of victory Coyolxāuhqui and her brothers were led to the top of the nearby ‘Sacred Snake’ mountain (Coatepec). One by one, Huītzilōpōchtli chopped off each one of the Centzón Huitznahuas’ heads and threw them up into the sky where they ‘lived’ up to their name as the 400 southern stars. Lastly, Huītzilōpōchtli ripped his sister Coyolxāuhqui apart by the limbs before decapitating her and tossing her head into the sky to become the moon and rolled her body off the side of the mountain as a warning to all future threats.

-(Braswell 2014)

Extra Details and Changes in Other Versions

Figure 9. (1) Huitzilopochtli springs from Coatlicue's womb fully armed and defends himself and his mother against Coyolxauhqui. (2) He dismembers his sister and fights his 400 brothers, the Centzon Huitznahuas (Bernadino de Sahagún).

In the most drastic departure from the previous version of this mythical duel, Coyolxāuhqui is Huītzilōpōchtli’s mother. One day she upset her son when she insisted on staying at the legendary sacred mountain Coatepec and not following Huītzilōpōchtli’s plan to re-settle at a new site – the future Tenochtitlan. The god of war got his way by decapitating and eating the heart of Coyolxāuhqui, after which he led the Mexica to their new home (Cartwright 2016). This version didn’t mention the other dismemberment or the monolith, so there is a possibility that it’s a version before the monolith was carved.

Smaller changes between versions appeared in the details that don’t change the whole story, such as why Cōātlīcue was sweeping. If she was just doing a job, fulfilling some penance, or if, as the maternal Earth deity, she was sweeping her own shrine. In what she did with the feathers. As the first version discussed, while performing her duties as a cleaner at the shrine on the top of the sacred mountain Coatepec, a ball of feathers suddenly descended from the heavens. Adjustments appear when Cōātlīcue tucked the ball into her belt and it miraculously impregnated her. When a ball of specifically hummingbird feathers fell from the sky, she "snatched them up; she placed them at her waist" and became pregnant. Or, when a single feather fell from the sky Cōātlīcue picked it up and placed it on her breast. When she finished sweeping she looked for the feather, couldn’t find it, and then realized she was pregnant. (Graulich, et al. 1981: 45–60, Kilroy-Ewbank 2015, Cartwright 2016, Britannica 2021, Graulich, et al. 1981: 45–60, Spence 2016: 70-72)

In every story, Cōātlīcue’s offspring were enraged to learn that their mother was pregnant and Coyolxāuhqui convinced them that their mother had dishonored them all and should die. Cōātlīcue is always said to be very scared and sad, but Huītzilōpōchtli, in her womb, told her not to fear because he would protect her and she felt comforted and calmed. In several versions, while Coyolxāuhqui and 399 of her Centzón Huitznahuas brothers planned revenge, one of them, named either Cuahuitlicac or Quauitlicac (or left unnamed), went looking for his mother and Huītzilōpōchtli to tell them that the warriors were making plans to kill them and would be on their way soon. In these versions, Cuahuitlicac/Quauitlicac is a named god of the northern stars as part of the Centzónmimixcoa "Four Hundred Mimixcoa" who had a completely different parentage than the brother in this story (Sahagún 1569, Graulich, et al. 1981: 45–60, Spence 2016: 70-72).

In the stories in which they were given advanced notice, the pregnant Cōātlīcue could miraculously gave birth to a fully grown and armed Huītzilōpōchtli who sprang from her womb, wielding his shield of eagle feathers, teueuelli, and his turquoise darts and his blue dart thrower, called xinatlatl. In one version, *Huītzilōpōchtli had enough preparation time to paint his arms and legs blue, draw diagonal stripes on his face, put on a crown of hummingbird feathers, and wear a feathered sandal on his right foot (Figure 9 - but wearing feathered sandals on both feet)(Inside-Mexico n.d.). However, for this character, the right foot doesn’t make sense because, as mentioned earlier, the name Huītzilōpōchtli means “Hummingbird to the left,” which arose from the circumstance that the god wore the feathers of the hummingbird, or colibri, on his left leg. From this, it has been inferred that he was a hummingbird totem (Spence 2016: 73).

Figure 10. The Statue of Cōātlīcue displayed in the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City was created in either 1439 or 1491 (Boone 1999).

In other versions, the god sprung from his mother's severed neck before two giant snake heads grew to replace it after Coyolxāuhqui had decapitated her. This shows up in the Cōātlīcue statue as well (Figure 10).

Either way, it was with his most formidable weapon, the xiuh cóatl (“turquoise snake” or 'Fire Serpent') which was a ray of the sun, that the warrior-god could use to swiftly butcher his unruly siblings. At least he used it to wound his sister, cutting off her head, and then threw it into the sky wherein it became the moon (Cartwright 2016, Britannica 2021).

While some variations said that Huītzilōpōchtli chopped up Coyolxāuhqui into several large chunks, which he lobbed down the mountainside, others say that after the decapitation he rolled or threw the body down which either would’ve caused the body to fall apart on the way or broke apart at the bottom (Graulich, et al. 1981: 45–60, Carrasco 1982: 167, Kilroy-Ewbank 2015, Cartwright 2016, Inside-Mexico n.d.). In one story Huītzilōpōchtli throws his sister’s body down the side of Coatepec: “He pierced Coyolxāuhqui, and then quickly struck off her head. It stopped there at the edge of Coatepetl. And her body came falling below; it fell breaking to pieces; in various places her arms, her legs, her body each fell” (Sahagún 1569).

And the last major change, even though the ending point would be the same, has to do with the star brothers. In at least one of the versions in which one of the brothers helped Huītzilōpōchtli, he chased the 399 brothers to the foot of the mountain after killing their sister. Many begged for forgiveness, but only a few escaped his ire and survived by heading south where they became stars rather than being dead heads in the sky like their sister (Sahagún 1569, Inside-Mexico n.d.). Otherwise, either 399 or the full 400 brothers would have been decapitated at Coatepec where their heads were also tossed into the sky.

Some authors have written that Huītzilōpōchtli tossed Coyolxāuhqui's head into the sky where it became the Moon and that her scattered brothers became the Southern Star deities so that his mother would be comforted in seeing her daughter in the sky every night (Durán 1964: 347).

A great video for an extra version:

Overly Sarcastic Productions - Huitzilophochtli

This gruesome myth focusing on sibling rivalry may have symbolized the daily victory of the Sun (one of Huītzilōpōchtli's associations) over the moon and stars. However, some scholars have argued that Coyolxāuhqui was associated with the Milky Way instead of being a direct lunar goddess (Cartwright 2016). This could be the reason that there is another moon goddess Mētztli (also rendered Meztli, Metzi) whose name means "Moon" (Tena-Colunga 1987: 2). It’s also possible that they were both the same deity as well as Yohaulticetl and the male moon god Tēcciztēcatl because they all had the domain also encompassing the moon, the night and (sometimes) farmers.

But, no matter how many sources we use, we can’t be sure of the original because the oldest versions weren’t written down until the 16th century, in the codices (as far as we know).

Image Analysis:

Monolith

With chemical analyses, we can look at the original cylinder and the vibrant colors to see how much it would stand apart from its surroundings (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Painted version of the Coyolxauhqui stone, with possible original colors based on the chemical analysis (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-SA 2.0).

In the artwork, Coyolxāuhqui is shown with bright yellow skin decapitated, dismembered, and surrounded by deep red blood. Standing out from the red blood background, sandals, accessories, and facial features are the bright blues of her eyes, headdress, “rope” knots, and various other details in the carving. Along with the white accessory details, the paint on her face, and the dots on her headdress, her white bones emerge from the scalloped edges of her dismembered body parts. She is wearing a ritual blue eagle-down feathered headdress, blue earrings for the Mexica year sign, a special cheek symbol of a bell, bracelets, sandals, a serpent loincloth, a skull on a belt of snakes, and her limbs are tied with ropes of snakes. To the Mexica, nudity would have been shameful, and thus would have been another way of breaking down her power and influence (Klein, 1994: 22). The body has sagging breasts with a wrinkled and sagging stomach and even though her head is shown as young to symbolize the differences between the ages of new and full moons. The last influence we see reflected from older cultures like the Olmec and Maya are the monster faces on her elbows and knees, reminding onlookers of snakes, skulls, and the Earth Monster.

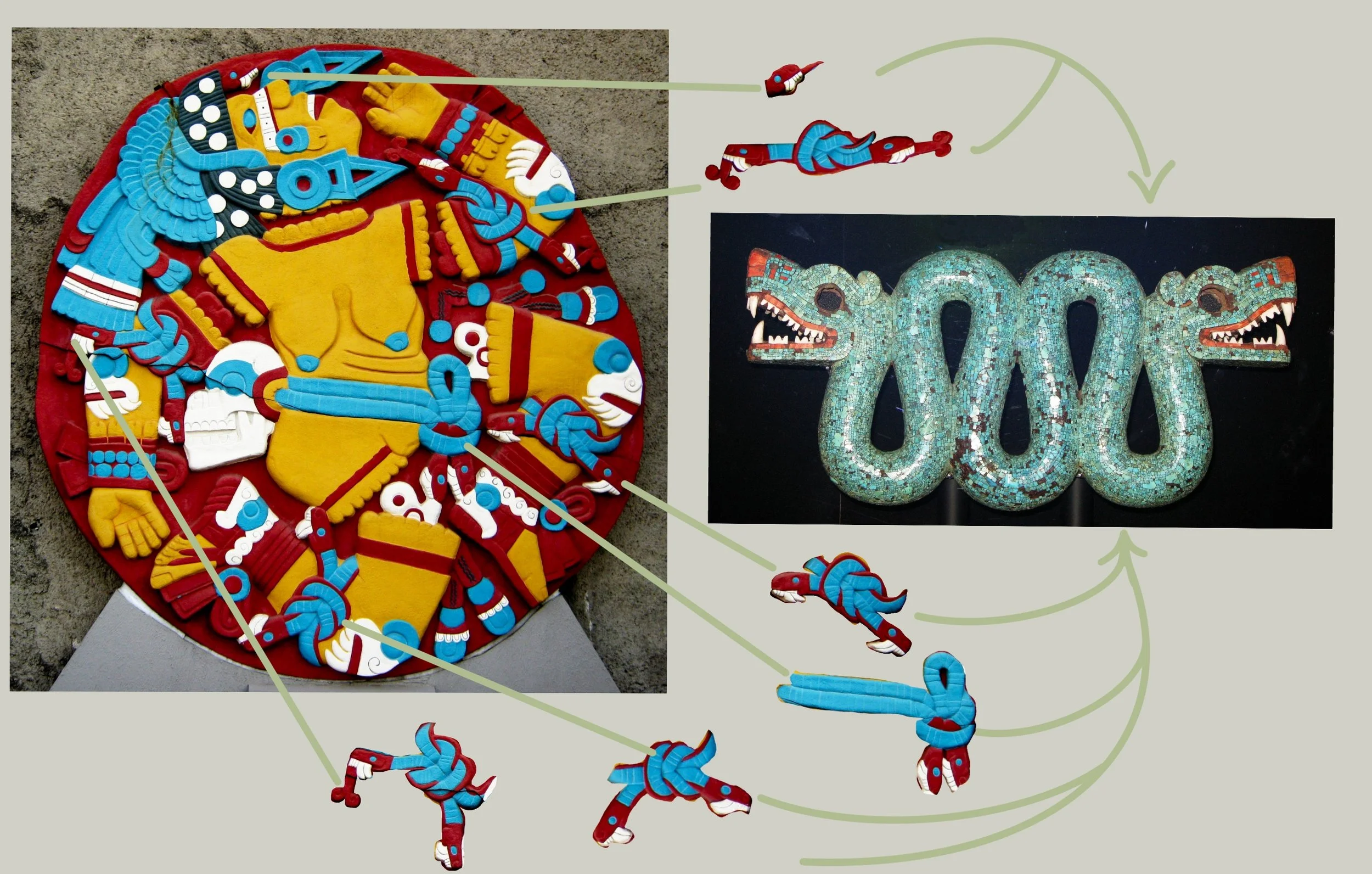

The rope knots are likely symbols of the double-headed serpent, known as Maquizcoatl**, which were negative omens that could indicate death. Associated with Huītzilōpōchtli as it was one of his names, creates a tie between the siblings. Coyolxāuhqui's joints being restrained by Maquizcoatl is both symbolic of her duty to serve a warning, as well as identifying the importance of rebirth (Aveni 1988: 287–309).

In Mexica religion, snake iconography is said to represent rebirth (because of its ability to shed its skin). The Maquizcoatl's two heads might have represented the Earth and the Underworld. The snake motif also alludes to the feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl, a symbol of death and resurrection in Mexica mythology. More broadly, the color green and serpents represent fertility, while turquoise used to create the sculpture motif represents fresh growth and water, guaranteeing that land fertility was central to most Mexica rituals. During rituals, priests wore the Quetzal bird's feathers on their headdresses, while the underlying snake head's vivid turquoise skin and wide jaws were meant to impress and frighten the observers (British Museum: 78).

Figure 10. Separating all double-headed serpents restraining the body parts of Coyolxāuhqui next to the reference of Maquizcoatl (YarelisMAlvarez).

The Coyolxāuhqui stone would have served as a cautionary sign to the enemies of Tenochtitlan. According to Mexica history, female deities such as Coyolxāuhqui were the first Mexica enemies to die in war. In this, Coyolxāuhqui came to represent all conquered enemies. Her violent death was a warning for the fate of those who crossed the Mexica people (Klein 1994: 22). Richard Townsend notes that the disk represented the defeat of the Mexica's enemies at large because sacrificial victims would have had to cross this stone before walking up the stairs of the temple to the block in front of Huītzilōpōchtli’s shrine (Townsend 1992: 161, 2009: 159).

Head

Figure 11. Left: Coyolxauhqui Statue, J Paul Getty Museum (photo by Jonathan Cardy)

Figure 12. Right: Head of Coyolxauhqui c. 1500; diorite; 80 x 80 x 65 cm (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City).

This head was also found at Tenochtitlan which was probably carved during the reign of Ahuitzotl (1486-1502 CE). Coyolxāuhqui is shown decapitated and with closed eyelids, because she was beheaded by her brother, Huītzilōpōchtli. This is different than the monolith and could have been influenced post-Contact. As her name suggests, and the same as the monolith the face has bells on her cheeks. She is also wearing the elaborate year-sign ear flares, a matching nose flare that falls over her lips, and a headdress patterned with feathers nearing the back, and lines and dots on the base. These would likely have been carved for a transportable symbol of the power of the Huītzilōpōchtli when sacrificing the captive enemies from war.

Role of sacrifice

Blood is extremely important in Mexica mythology, as it keeps the Earth from eating us (Overly Sarcastic Productions - The Creation of the Earth) so sacrifice was integral to the religion. Scholars believe that the decapitation and destruction of Coyolxāuhqui is reflected in the pattern of warrior ritual sacrifice, particularly during the feast of Panquetzaliztli (Banner Raising). The feast takes place in the 15th month of the Mexica calendar and is dedicated to Huītzilōpōchtli (de Tovar 1585). During the ceremony, the hearts of captives were cut out and their bodies were thrown down the temple stairs to the Coyolxāuhqui stone. There, they were decapitated and dismembered, just as Coyolxāuhqui was by Huītzilōpōchtli on top of Coatepec (Matos Moctezuma 1983: 192).

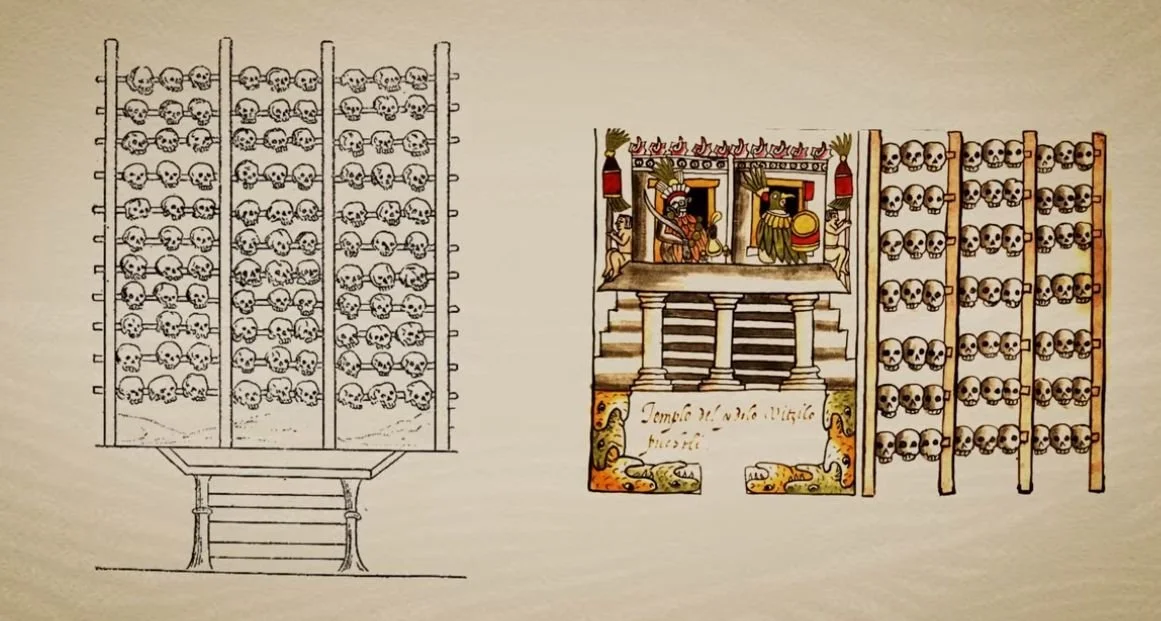

Figure 11. Illustration of a tzompantli c. 1587 Aztec Manuscript, The Codex Tovar (Wikimedia Commons).

Figure 12. Symbolic skull rack monument in Chichen Itza (Whitehouse 2013).

The heads of enemies that would be sacrificed at the top of the stairs of a temple pyramid would later be placed in a tzompantli, a skull rack (Figure 11). In some other areas in the Mesoamerican world (for example: from the Toltec culture and in Chichen Itza) these were only symbolic, being carved out of rock (Figure 12-13). While there was human sacrifice, it wasn't always necessary, much like ushabtis in Egypt. Like with the Maya, bloodletting was a common practice in the Mexica religion wherein the kings and queens would sacrifice their blood by kings piercing their penises with a stingray spine and anyone piercing their tongues and running a rope of thorns through the hole (Figure 14-16). The dripping blood catches on cotton strips which were then burnt as offerings so the smoke goes to the Gods in the heavens. But, what is remembered more commonly from both cultural traditions are the heart removals and the decapitations which were exhibited on the top of the pyramids in front of huge crowds.

Figure 13. Symbolic Skull rack constructed in close proximity to the Templo Mayor in Mexico City. From the line to enter the Museo Nacional de Antropología (Whitehouse 2014).

Figure 14. Maya Limestone Yaxchilan Lintel 24. Records a bloodletting ritual that took place on October 28, 709 AD. Shield Jaguar holds a torch while his consort, Lady Xoc, pulls a rope studded with what are now believed to be obsidian shards through her tongue to conjure a vision serpent (British Museum).

Figure 15. Bloodletting scene from Yaxchilan Lintel 17. This image of Classic Maya bloodletting depicts a royal man using a stingray spine to pierce his penis and a noblewoman pulling a thorny vine through her tongue in ritual acts of self-sacrifice. (Drawing by Ian Graham [81] © President and Fellows of Harvard University, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004)

Figure 16. Mexica priests draw blood from their bodies with skewers and knives to appease Mictlantecuhtli, Lord of the Underworld (New York Public Library / Science Source).

Conclusions

Coyolxāuhqui was and is seen as the villain of the story, which seems pretty obvious, but after reading [Un]Framing the "Bad Woman" by Alicia Gaspar de Alba I got angry for Coyolxāuhqui. As there are so many versions, these are part of a longer and more in-depth story. Gaspar de Alba’s analysis is deep and goes into the extra backstory behind the characters. For a quick example, Cōātlīcue and her family served other gods, as evidenced by Cōātlīcue sweeping in a temple as a service of penance. For what, we aren’t told; for whom, also don't know. But, even when she is an Earth goddess, why is she sweeping her own temple (not that she couldn’t)? But, then how Huītzilōpōchtli was “getting inside” his new unknowing and nonconsenting mother (sounds like the women in every story involving Zeus) started a new religious following and involved building a new temple. But it started with the pilgrimage from the Coatepec mountain, which was said to be in Tula, a site in Hildago, Mexico which would have been about a day’s walk south to the future site of the Templo Mayor on the swampy island in Lake Texcoco.

People don't care for being told that they can't follow their religion anymore or more generally live how they are used to. We know this from what happened with Akhenaten in Egypt or any of the times European monarchies switched between the versions of Christianity. Protecting what we know is completely fair. There's more to all of these stories that have been told, and we can't pretend that the Spanish Conquistadors didn't play into the twisting tales to suit their ends. Summarized from Gaspar de Alba, the Christian conquerors would have approved of a peace-bringing, immaculately conceived son coming into this world and starting a new religion and, therefore, anyone against them is evil. Though to be clear, the myth and the monolith both existed pre-Contact. But could this be why the story could have so dramatically changed from one version to another? Was it a way of purging the earlier depictions of mythological figures in favor of the new Mexica main deity? I don’t know and we can never really know for sure. So, to avoid diving far further into a full thesis I will just say that there is a more nuanced view of human sacrifice in various cultures around the world and how the causes and effects are built into a peaceful worldview.

In various cultures around the world, the theme of devotion and connection to one's family is deeply intertwined with the concepts of power and the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. It is believed that individuals who are devoted to their families and communities are seen as deserving of power bestowed upon them by the gods. This is why Coyolxāuhqui and her brothers needed to be punished for trying to kill their mother. This power is not just physical or material, but also spiritual and cosmic, symbolizing the interconnectedness of all living beings. The act of human sacrifice, often depicted in Mesoamerican art, represents a sacrifice for the greater good of sustaining this cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Through these rituals, the connection between the human and divine realms is reinforced, showcasing a profound understanding of the complexities of existence and the importance of navigating them.

In wrapping up this exploration of the story of Coyolxāuhqui, a Mexica goddess of the moon, we are left with a profound sense of awe and wonder at the complexities of mythology. Through her fragmented representation, we glimpse the intricate layers of symbolism and meaning that defined Mexica beliefs. Coyolxāuhqui's story serves as a reminder of the eternal struggle between light and darkness, life and death, and the importance of the inevitable cycles of rebirth. She is a powerful symbol of transformation, resilience, and the enduring power of myth to transcend time and influence artistic interpretations and cultural narratives to this day.

Asides:

*Huītzilōpōchtli was usually represented as wearing on his head a waving panache or plume of hummingbirds’ feathers. Similar to his body paint in the myth, his face and limbs were striped with bars of blue. He carried four spears tipped with tufts of down instead of flint in his right hand and his shield made of reeds, which displayed five tufts of eagle’s down, arranged in the form of a quincunx (five dots like on a dice) in his left. (Spence 2016: 73).

**The Maquizcoatl snake with two heads composed of mostly turquoise pieces applied to a wooden base. It came from Aztec, Mexico and might have been worn or displayed in religious ceremonies (British Museum 78). The mosaic is made of pieces of turquoise, spiny oyster and conch shell (McEwan 2006).

***Other notable representations of Coyolxauhqui are a fragmentary greenstone (diorite) slab (which is older) and a stucco sculpture of the goddess lay beneath the stone disk.

Aztec Empire was only ~90 years old at the time Cortez allied with a bunch of other Indigenous groups in the region to take them down.

Work Cited:

Aveni, A. (April 1988). "Myth, Environment, and the Orientation of the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan". American Antiquity. 53 (2): 287–309.

"Aztec Skull Trophy Rack Discovered At Mexico City’s Templo Mayor Ruin Site". The Guardian, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/aug/21/aztec-skull-trophy-rack-discovered-mexico-citys-templo-mayor-ruin-site.

Boone, Elizabeth (1999). "THE "COATLICUES" AT THE TEMPLO MAYOR". Ancient Mesoamerica. 10 (2): 189–206.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2021, August 30). Huitzilopochtli. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Huitzilopochtli.

British Museum. “Double-headed serpent”. A History of the World in 100 Objects, BBC. 78.

Braswell, Geoffrey. (June, 2014). The Aztecs and their Ancestors - Study Abroad. UC San Diego.

Carrasco, David (1982). Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of the Empire. Boulder, Colorado: The University of Chicago Press. p. 167

Cartwright, M. (2016, February 11). “Coyolxauhqui”. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Coyolxauhqui/

de Tovar, Juan(1585). The Tovar Codex.

Durán, Fray Diego (1964). Heyden, Doris; Horcasitas, Fernando (eds.). The Aztecs: The History of the Indies of New Spain. Orion Press. p. 347.

Gaspar de Alba, Alicia. [Un] framing the" Bad Woman": Sor Juana, Malinche, Coyolxauhqui, and Other Rebels with a Cause. University of Texas Press, 2014. pp. 175-202.

Graulich, M., Carrasco, P., Coe, M. D., De Durand-Forest, J., Galinier, J., González, Y., Heyden, D., Piho, V., Kelley, D. H., Kolb, C. C., Reinhold, M., Riese, B., Stewart, J. D., & Tichy, F. (1981). The Metaphor of the Day in Ancient Mexican Myth and Ritual [and Comments and Reply]. Current Anthropology, 22(1), 45–60.

Inside-Mexico (n.d.) “The Legend of Coatlicue & Coyolxauhqui”. Myth & Legends. Inside Mexico. https://www.inside-mexico.com/the-legend-of-coatlicue-coyolxauhqui/

Kilroy-Ewbank, Lauren."The Templo Mayor and the Coyolxauhqui Stone," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed April 15, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/templo-mayor-at-tenochtitlan-the-coyolxauhqui-stone-and-an-olmec-mask/.

Klein, Cecilia (1994). "Fighting with femininity: Gender and war in Aztec Mexico". Estudios de cultura náhuat. 24: 22.

Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo (October 1983). "Symbolism of the Templo Mayor". The Aztec Templo Mayor: A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks: 192.

McEwan, C. (2006). Turquoise Mosaics from Mexico. Duke University Press.

Milbrath, Susan. “Decapitated Lunar Goddesses in Aztec Art, Myth, and Ritual.” Ancient Mesoamerica, vol. 8, no. 2, 1997, pp. 185–206. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26307242.

Olvera, Alfonso. "The Legend Of Coatlicue & Coyolxauhqui | Inside Mexico". Inside-Mexico.Com, 2016, https://www.inside-mexico.com/the-legend-of-coatlicue-coyolxauhqui/.

Sahagún, Bernadino (1569). Florentine Codex Book 3.

Solis, Felipe; Angel Gallegos (August 2000). "El Templo Mayor de Mexico-Tenochtitlan". Mexico Desconocido (in Spanish). 45 (91).

Spence, L. (2016, September 18). The Myths of Mexico & Peru. The Project Gutenburg EBook. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/53080/53080-h/53080-h/htm.

Tena-Colunga, Arturo. (1987). “The Meaning of the Word México”. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Townsend, Richard F.

(1992). The Aztecs. London: Thames and Hudson. 161.

(2009). The Aztecs (3rd ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. 57.

Please visit my Patreon!!: patreon.com/DetoursinArtaeology