Jack of the Dancing Flames

For the enjoyment of the season, I decided to look into a folklore that is as Halloween as Halloween can get, Jack o' Lanterns. They appear on the doorstep of most suburban houses, in the United States, from where they light the way for children to collect their sugary treats each Halloween night. As the US was founded and run by a bunch of white guys, basically from England, we get a lot of our folklore and traditions from that region. From the broadest research and general Halloween stories passed down through the generations, we know that Halloween traditions were passed down and altered from the Gaelic autumn festival Samhain. The greatest examples of this continuation were the lanterns made of turnips and then pumpkins, the latter of which show up in various spooky stories.

Figures 1-2. The Great Jack O’Lantern Blaze in Hudson Valley, New York. Unknown Artist. Photograph: Courtesy Jennifer Mitchell. Article by Jennifer Picht and Collier Sutter Posted: Friday, September 25 2020 on TimeOut.com

Figure 3. Jack-o'-lantern made by Reddit user u/Hoturan's girlfriend (2017).

The Horsemen, who happens to be Headless

“Well, gather round and I’ll elucidate” a tale we’ve all heard about the legend of Sleepy Hollow in which the Headless Horseman was a dead Hessian who died by a cannonball to the head syndrome in a “nameless battle” in the Revolutionary War. He was said to have a Jack o' lantern for a head and would throw it at his victims or chop off their heads with a slice of the sword (Disney, 1949; Irving, 1820) after “being bewitched during the early days of the Dutch settlement; [… or] that an old Indian chief, the wizard of his tribe, held his powwows there before the country was discovered by Master Hendrick Hudson” (Irving, 1820: 2). But, this idea of the jack-o-lantern was clearly a well-known staple of Washington Irving’s 1820 fictional written retelling of the Sleepy Hollow legend, set in 1790 in a sleepy little town around the Dutch Settlement of Tarry Town, New York. As this was a retelling of the story there are plenty of variations between the oral folklore and what was written down, like the reason for the curse itself and as the first ghost story is as changeable as any mythology.

Figure 4. Ichabod pursued by the Headless Horseman by F.O.C. Darley - Le Magasin pittoresque (1849).

Figure 5. The Headless Horseman Pursuing Ichabod Crane (1858) by John Quidor.

Figure 6. The Original Headless Horseman from Monstrum (2018).

Figure 7. The remnants of the pumpkin and Ichabod: From The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (Disney, 1949).

The headless horseman isn’t written to have a jack o' lantern as a head, Irving wrote “his horror was still more increased on observing that the stranger's head was carried before him on the pommel of the saddle” (Irving, 1820: 12) and when Crane had disappeared after being chased the clues found were a beaten saddle, the schoolmaster/school choir leader’s hat, and a shattered pumpkin, but it’s never explicitly stated that the jack-o-lantern was acting as his head. This might have been altered to make the cartoon a bit less gory, but possibly it was assumed that “in the very act of hurling his head at him” (Irving, 1820: 13) the pumpkin evidence was the head he threw (Figure 7).

Tales from the Celts

The Dullahan searching for his next victim. From The Irish Place.

The jack o' lantern showing up as the head prop could also attribute some of its roots to the headless horseman from Celtic folklore, Dullahan, Dullaghan, or in the specifically Irish origin Irish Gælic: dúlachán, /ˈduːləˌhɑːn/), also called Gan Ceann, meaning "without a head" (Croften, 1834). This horseman/carriage driver doesn’t carry a jack-o-lantern either, but he is known to carry his own rotting corpse head on his arm with a light inside to act as his lantern as he whips his horse with an old victim’s spine (Harris, 2017).

The supernatural nature of such characters is evident in medieval literature, as seen in the faeish Green Knight from "Gawain and the Green Knight," who could survive decapitation (Krappe, 1938). Irish mythology significantly influenced European literature, particularly in developing Arthurian legends and the Grail quest (Loomis, 1933). This cultural exchange occurred during Ireland's period as a center of Christian scholarship from 500-850 CE (Loomis, 1933).

ADD PHOTO GREEN KnIGHT Figure 8.

The Dullaghan is also sometimes seen as an embodiment of the Celtic god/folkloric character Crom Dubh, in Scottish Gælic and Old Irish the name means “dark, crooked [one]”, who is in turn related to the older pre-Christian Irish God Crom Cruach [aka Crom Cróich, Cenn Cruach/Cróich, and Cenncroithi]. The major connection that Crom Crauch has with Halloween is the festival, Domhnach Crom Dubh, which celebrates the god of fertility on the last Sunday in July. The festivities would include the ancient practice of human sacrifice and the gifts of mounds of grain, hay, peat, and other gathered goods at Summer’s end in late July or early August, around the same time as Samhain, which even though it could directly break down as sam- “summer” and fuin “end” (Vendryes, 1959). This led linguist Vendryes (1959) to suggest that this translation is just folk etymology because the original version of the holiday would take place in August when summer ends. The word could also be translated from the Proto-Celtic Samani ("assembly"), suggested by the Irish lawyer Whitley Stokes (1907). Alternatively, Samhain means November in Irish, therefore, it could have been a name given to a celebration ushering in a new part of the year.

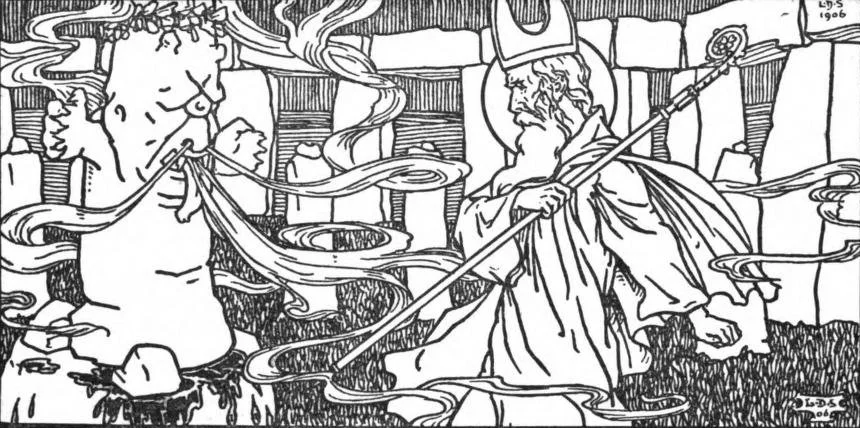

Figure 9. St. Patrick and Crom Cruaich. Illustrated by L.D.Symington. 1907.

No matter when the festival of Samhain took place, the purpose was to celebrate the end of the harvest season and summer and to welcome in the winter. This short intervening period was marked by the belief that the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead is the thinnest, allowing spirits to come back into our world. This is when the ghost stories and jack o’ lanterns come into play. By looking frightening, the candle-lit lanterns of grotesque faces on the carved turnips, beets, and potatoes protected the homes from the supernatural beings (the Aos Sí) and the souls of the dead when placed on windowsills or on doorsteps (Hutton, 1996; Palmer, 1973).

Figure 10. A traditional Irish turnip Jack-o'-lantern from the early 20th century. Photographed at the Museum of Country Life, Ireland: Photo from Rannpháirtí anaithnid in 2009.

According to Hutton (1996) and Palmer (1973) these pieces of apotropaic magic were both to frighten people and to ward off evil spirits. This also could harken back to earlier traditions and creates a barrier between the owners’ land and everything else (Stilgoe, 1976), which has a strangely equivalent, but unconnected idea to the Herma of ancient Greece. These boundary and road markers were commonly either stacked stone or more specially carved stone or wooden heads of the god Hermes (of fertility, luck, travellers, roads, and boundaries), his older Mycenaean counterpart Pan (of the wilderness and madness), or of other human heads; often even complete with legendary dongs (Paus. vii. 22. § 2; Aristoph. Plut. 1121, 1144; Hom. Od. xiv. 435, xix. 397; Athen. i. p. 16). What’s an even more lovely connection is that one of Hermes’ epithets was as a psychopomp, one who leads souls of the dead to the afterlife (Burkert, 1985:157–158.; Powell, 2015:179, 295), like the lanterns in other cultures (which I’ll discuss later) and the Jack o’ lanterns that may light and lure the souls to the houses, but act like gargoyles and grotesques, protecting the home from intruders. They also, like jack o’ lanterns, have use in ancient Greece “to ward off harm or evil, [their] apotropaic function, and were placed at crossings, country borders and boundaries as protection, in front of temples, near to tombs, outside houses, in the gymnasia, palaestrae, libraries, porticoes, and public places, at the corners of streets, on high roads as sign-posts, with distances inscribed upon them” and when placed outside of homes where seen as good luck (Brunck, Anal. 3.197, no. 234; Thuc. 6.27; Aelian, Ael. VH 2.41; Suid. s.v. Pollux, 8.72; Athen. 10.437b).

Figure 12. Herma with the head of Herakles (Hermherakles). Museum of Ancient Messene, Greece.

Figure 13. Herma of Demosthenes, from the Athenian Agora. Copy of an honour posthumous statue of the statesman on the marketplace of Athens; work by Polyeuktos (ca. 280 BC). Glyptothek

Figure 14. ADD PHOTO OF PSYCHOPOMP

*The pumpkin was not used in the tradition until the 19th century because the orange species of squash known colloquially as a pumpkin is a plant native to America and the Irish immigrants started using them in their traditions soon after their mass emigration out of Ireland because of the infamous potato famine. However, it quickly became very popular to use the larger, easier-to-carve squash and gourds.

A Cursed Man

But how did these creatures get their name? None of the headless horsemen, nor gods had the provincial name Jack. And that may have been the point, Jack is a name in fairy and folk tales for ‘common man’ or the everyman; like Jack and the Beanstalk and Jack and Jill and a Jack of all Trades. But the Irish legend of Stingy Jack is believed to have been the source of the Jack o’ Lantern name (Hofherr & Turchi, 2014). One version of the tale was published on Halloween in 1835 in the Dublin Penny Journal (Dublin Penny Journal, 1835: 3-4). We all know how differently stories can be told depending on time and location:

Figure 14. Stingy Jack by CricketBow Design

Figure 15. "The old Irish tale of Stingy Jack explains the origin of the Jack-o’-Lantern." Image by Jovan Ukropina. (Historic Mysteries)

Figure 16. Stingy Jack and his lantern turnip - from the Cryptic Chronicles Podcast website

Stingy Jack was a miserly drunk, who commonly lied and manipulated others in the town. [The tale varies widely on the introduction of the Devil, depending on who’s telling it.] He was drinking in a bar late one night when he drank himself silly. ‘For some reason’, this is the night that the Devil chose to play with him (the perfect time). Jack saw the Devil in the bar, and not wanting to pay for any of his drinks, Jack asked the Devil to sit down with him and have a drink, to which the Devil obliged. Of course, Stingy Jack didn’t want to pay, being true to his name, and convinced the Devil to turn himself into a coin in Jack’s purse (cause he could do that) to pay for the drinks. Then he could turn back into himself later, which would be a hilarious joke on the bartender (who's just trying to do his job). Once the Devil did so, he was pissed to find himself trapped because Jack kept his purse in his pocket next to a silver cross, which prevented the Devil from changing back into his original form. Eventually, Jack freed the Devil, under the condition that he would not bother Jack for one year and if Jack died, he would not claim his soul.

During the next year, Jack tricked the Devil again into climbing into an apple tree to pick a piece of fruit. While he was up in the tree, Jack carved multiple signs of the cross into the tree’s bark so that the Devil couldn’t come down until the Devil promised Jack not to bother him for another ten years. Not long after, Jack died. As the legend goes, God would not allow such an unsavoury figure into heaven. And when sent to Hell the Devil, who was still upset by the tricks Jack had played on him and bound by keeping his word not to claim Jack’s soul, would not allow Jack into hell. Either as a mocking sentiment or maybe a bit of pity he tossed a burning coal to Jack and sent him off into the dark night with only that to light his way. Jack put the glowing coal into a carved-out turnip or rutabaga, his favourite food, turning the root into a lantern. Jack, becoming Jack of the Lantern has been roaming the Earth ever since, as one of the many spirits that his namesake are carved to ward against (History.com Editors 2019; Hofherr & Turchi 2014; Lincoln 2004).

Of course, this gives the roots of the name to a time when Ireland was under Christian rule, but we are already aware that the practice is older than that, even going back to 500 BCE (Mullally, 2016: 34–37). The Christian monks who travelled to the Celtic people were the ones who wrote the records, so much of the mythology was changed to folklore. Gods changed to strong, but regular human beings, either by the monks or by the people relaying the stories, which, luckily, kept them within the cultural lexicon.

And even today, we like to interpret the Jack o’ Lantern trickster character in new ways. The version I enjoy best is Jack from the 2003 Halloween episode of The Grim Adventures of Billy and Mandy: Billy and Mandy’s Jacked Up Halloween.

Jack’s origin story: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zqbijmW2SBU

“Oh, I’m so sure! Jack the evil pumpkin-headed prankster. Well I don’t buy it.” – Billy

'Jack Shroud' from the 2003 Halloween episode Added by PyroGothNerd

GIF of Jack. Added by PyroGothNerd

*I’m surprised that so many drawings show Jack o’ lantern-headed scarecrows. One since crows are omnivores and would be attracted to free pumpkin yummy goodness and two they rot pretty quickly so farmers would have to replace them every week or so.

1) Scary jack-o-lantern scarecrow and crows gear: http://www.cafepress.com/offthewall5/9385264

2) *Jack o' lantern-seption*: 2014-01-23 22.25.09 by Slayersrx7 - https://www.deviantart.com/slayersrx7/art/2014-01-23-22-25-09-462461299

3) From Google-ing scarecrow Jack o' lanterns

The concept of a headless horsemen also appears in various Asian folklore traditions. In Chinese medieval prose, a story of a delayed-death headless horseman dates back to the 5th-6th centuries, with parallels in South Chinese, North Indian, and medieval Russian folklore (Starostina, 2022). Chinese travel books from the 12th-14th centuries describe Southeast Asian beings whose heads detach at night to feast on fish or human entrails, a belief confirmed by ethnographic studies and present in southern Chinese legends from the first centuries CE (Drège, 2015).

Recent archaeological discoveries have revealed unusual Scythian burial customs involving headless horsemen. A burial from the 5th-4th century BCE near Kustorivka village in the Krasnokutsky district, Kharkov region contained a decapitated man, horse remains, and weapons, hinting at a particular funeral tradition (Kozak et al., 2021). Similar findings in the South Caucasus show that Cimmerian-Scythian burials often featured horsemen with their horses and specific items (Tumanyan, 2017). Analysis of two Scythian skeletons from Alexandropol, Ukraine, dated to 325 BCE, showed evidence of a tough life on horseback and possible sacrificial rituals (Wentz & Grummond, 2009). These individuals may have served a Scythian king in life and death reflecting the Scythians' nomadic lifestyle and warrior society (Kozak et al., 2021; Tumanyan, 2017; Wentz & Grummond, 2009). .

Dancing Jack o’ Lanterns and Will of the Wisps

The term jack o' lantern was originally used to describe the visual phenomenon ignis fatuus (lit., "foolish fire") known as a will o'the wisp in English folklore. Used especially in East England, its earliest known use dates to the 1660s (Harper, Etymological Dict). The term "will o'the wisp" uses "wisp" (a bundle of sticks or paper sometimes used as a torch) and the proper name "Will": thus, "Will-of-the-torch." The term jack o' lantern is of the same construction: "Jack of [the] lantern”.

1) The Will o' the Wisp and the Snake by Hermann Hendrich (1854–1931)

2) Das Irrlicht, 1862 oil painting of a will-o'-the-wisp by Arnold Böcklin.

3) Do Not Follow the Feu Follet. From https://www.visitlakecharles.org/blog/post/feu-Follet/

4) Will with a Wisp from Tales of the Wisp.

In several more stories, the Jack o’ lantern shows up to dance, just like wills o’ the wisp. These mysterious flames dance over the peat bogs of Ireland and Scotland, and as we’ve heard from stories of the fairies of old, in the more recent 'UFO' sightings, or tourists stumbling upon the well-preserved bog mummies that are created up in the frightening bogs, these entities will lead people off the path and possibly to their doom. But, the jack o’ lantern/will o’ the wisp idea was not confined to the British Isles. The stories extended to the Netherlands and to the Northern Germanic area where there was a specific way of getting rid of them.

Jack o’ Lanterns with the Long Legs

One late night in the German town of Hermsdorf a peasant was walking home when he saw a lone Jack o’ lantern. Since it had no reason for being out there the peasant thought it odd and because the peasant was “of a courageous nature”, he walked up to it. The Jack o’ lantern popped to life and tried to run away, with the peasant following close behind observing that ‘he’ [for some reason they gendered a carved pumpkin] had the “most wonderfully long legs, and from top to toe consisted of glowing fire”. Within the same instant, the Jack o’ lantern was said to vanish, and the peasant who gave chase could barely find his way back in the dark.

Jack o’ Lanterns Being Driven Away by Cursing

In Storkow there was a clergyman and his servant driving home one late night. Once they reached “a certain spot” they both saw a Jack o’ lantern dancing towards them. More and more of them started appearing out of the surrounding forest. At this point, the horses wouldn’t move and the clergyman could only think to pray aloud; so, he did. Unfortunately, the praying backfired and the more he prayed, the more dancing Jack o’ lanterns appeared. The servant, sick of these shenanigans yelled out ' “Just leave that off; so they will; but I’ll send them packing" … "Will ye be off in the devil’s name!" '. And that moment all the Jack o’ lanterns were gone.

Jack o’ Lantern Caught

Once there was a cowherd near Rathenow who, after spending all day out with the cattle, returned home with one of them missing. The cowherd went out immediately to look for her in the forest. After hours of searching, he got super tired and had to sit down. While sitting a spell and filling up his pipe the cowherd saw a countless number of Jack o’ lanterns come dancing towards and around him. He was also super brave, so he just kept filling his pipe. He was about to light up when the Jack o’ lanterns started flying around his head while flames spurted out toward the man. He then grabbed a large stick and started swinging at the orbiting Jack o’ lanterns, but the more he swung the more Jack o’ lanterns showed up. Fed up with all this the cowherd reached out and grabbed one, and when he looked at what he was holding it was a bone. That second all the Jack o’ lanterns disappeared, the cowherd stuck the bone in his pocket, finally lit his pipe, and walked home. The next morning, he found the lost cow, lived through the day, and returned home safely. But, once night had fallen the cowherd saw lanterns coming towards his house; it was a huge group of Jack o’ lanterns, all crying out ‘ “[i]f you don’t give us our comrade, we will burn your house!” ‘ After a minute of disbelief that the bone could be their comrade the cowherd threw the bone out the window wherein it turned back into a “bright flickering Jack o’ lantern, and danced away”, joining all the joyous others as they left the village.

All three stories were from:

Northern Mythology: North German and Netherlandish popular traditions and superstitions. Compiled by Benjamin Thorpe in 1852, pages 85-86.

In a rhyme by Cornish folklorist Dr. Thomas Quiller Couch (d. 1884) that takes place in Polperro, Cornwall, the Jack o’ Lantern, along with Joan the Wad, the Cornish version of Will-o'-the-wisp are tricksy characters. Because of the familiarities between the mysterious light ‘characters’, the people of Polperro regarded both groups as pixies.

Jack o' the lantern! Joan the wad,

Who tickled the maid and made her mad

Light me home, the weather's bad.

(Simpson & Roud, 2000).

Will o’ the Wisps were considered as part of the lower spirits and were personified flickering flames and also connected with wights and elves from the Germanic linguistic context (Grimm, 1883; Hand, 1977). And in the Pennsylvania German culture the term “Drach”, as in a fiery, dragon creature, was used to designate the Will of the Wisps and the Jack o’ Lanterns that followed the timid (Hoffman, 1889 in Hand, 1977). Charles P.G. Scott (1895) must have been more Christian because he connected the flickering lights with the devil and his imps and gave a lot of variations on the name, for example, “Billy of the Wisp” (Hand, 1977). Otherwise, the Will o’ the Wisp is generally known as a manifestation of supernatural light in Wales and adopted in Scotland they would also be known as elf-candles or corpse-candles after the Latin “quasi-scientific term” ignis fatuus (ignis: fire; fatuus: giddy, wild, silly) even though there isn’t evidence that the Will o’ the Wisp was ever a Greco-Roman mythological idea (Phipson, 1868: 392-399). After all, the major times when it does appear in literature is by mostly English scientists and authors; Roger Bacon (in the 13th century- perhaps the first time it was written), a line in Shakespeare’s Henry IV (part i. act iii. Scene 3) – around 1590, Newton’s 1672 Opticks, and the French chemist Lemery who, in 1675, attempted to accurately scientifically define the phenomena with chemistry, harkening back to the ancient people who defined them as naphtha or petroleum flames (Phipson, 1868: 392-399).

Ignis Fatuus, Study 9 © Frang Dushaj

Moths to the Flame? Or Flowers Towards the Sun?

As an interesting worldwide phenomenon will o'the wisps also appear in other cultures. The Chir batti, or ghost-light, is a dancing ball of light over India's Banni grasslands, a seasonal marshy wetland (Maheshwari, 2007). The Aleya or marsh ghost-light, is the name given to the strange little light by the Bengali people, of which it is said that the light is a type of marsh gas that confuses fishermen and makes them lose their bearings and may lead to them drowning (Pandey, 2007). While, in Japan, the wisps are known as Hitodama, which translates to "human soul as a ball of energy", and are associated with graveyards but are said to be seen all over Japan (Mitzuki, 1985). Also in Japan, specific yokai demons called kitsune would be married and the offspring of these two kitsune are called kitsune-bi (狐火), literally translating to 'fox-fire' (Lombardi).

An Australian equivalent, known as the Min Min light is reportedly seen in parts of the outback after dark with the majority of sightings occurring in the Channel Country region, but also around the continent these stories even appeared before colonists ever arrived in Australia (Kozicka; Pettigrew, 2003). Finally, around and near Mexico the balls of light are believed to be brujas (witches) who had transformed into these lights although the reasons for this vary according to the region (Wiki). But, another explanation refers to the lights as indicators of places where gold or hidden treasures are buried which can be found only with the help of children, in this one they are called luces del dinero (money lights) or luces del tesoro (treasure lights). There are many more examples, but it's clear to see that the will of the wisp aka floating balls of light is a common occurrence in most (if not all) folklore, whether as an evil being, a protector, or just a force of true neutrality, or rather a pure force of nature.

1) Chir Batti and Aleya Chir Batti, Chhir Batti or Cheer batti (Ghost light) - Spreading Geologic Knowledge

2) A Japanese rendition of a Russian will-o'-the-wisp: Unknown author - Kaikidan ekotoba (怪奇談絵詞, Japanese picture) (1853).

3) Min Min sign in Boulia, outback Queensland, Australia. Taken in 2006 from gondwananet.com.

The idea that lanterns are for showing the spirits of ancestors the way, is also a common practice in the unconnected, disparate cultures within the multitude of Asian and Latin American cultures. Día De Los Muertos, though this holiday was also influenced and altered by the Conquistador Catholics its elements are rooted in Aztec and elder belief systems (Valdez, 2017). Also, specifically for the observance and remembrance of ancestors is the over 2000 years running Qingming Festival in China, with equivalencies in Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Singapore, to name a few. During this holiday the temples and tombs are cleaned, and the living visit the dead with food, drink, burning papers and lighting fireworks (Uiowa.edu, 19 November 2014; Taiwan.gov.tw, 2014). On the other side is the Buddhist and Taoist [Hungry] Ghost Festival and its various counterparts all across Asia are the closer versions to the European Halloween, when the spirits of the dead return to our plane (China Daily. August 8, 2014). In this, the lanterns are candles in paper folded like the lotus flower and floated down the rivers and out to sea to guide the lost souls of forgotten ancestors to the afterlife ("Hungry Ghost Festival", 2002).

1) "Altar tradicional de día de muertos en Milpa Alta, México DF." by Eneas de Troya - https://www.flickr.com/photos/eneas/4072192627/ (2009).

2) "Cempasúchil, alfeñiques and papel picado used to decorate an altar. This image represents the Catrina, a female character representing the dead created by Guadalupe Posadas" (Paolaricaurte, 2015).

2) Figure 3: Chinese Floating Lotus Lanterns From The Yu Lan Hungry Ghost Festival by Tuyen Ta Hoang, April 23, 2018

3) Qingming Festival (Source: The World of Chinese). Posted on: April 05, 2018.

4) The 'Hungry Ghost' Festival from Living Life in Full Spectrum, 2018

5) "On the evening of August 16, 2016, tens of thousands of people in Ziyuan County, Guilin, G uangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region participate in river lantern drifting activities along the Zijiang River, praying for good weather and peace." - Source: China Today, staff reporter DANG XIAOFEI, 2019.

6) "A Chinese woman offers joss sticks during the Hungry Ghost Festival in Singapore" (Cedric Tan, 2018) Photo: AFP.

Conclusion

Within these various and diverse cultures, the roots, squash, paper, and other specially crafted lanterns were thoughtfully designed for the deep love of bringing the ancestors to visit with their still-living family members, and it is customary to gift them their favorite food and drink as a way to appease the visiting spirits. Alternatively, these lanterns were often hand-crafted with the intention of protecting the family members inside the home from unwanted harm and creating a warm, inviting atmosphere. In either case, these beautifully made ‘lanterns’ are works of art and are important historical puzzle pieces that we are incredibly lucky to still have among our traditions today.

The connection between the jack-o' lantern and will-o'-the-wisp folklore reveals a fascinating tapestry of cultural beliefs surrounding light and the unseen. Both symbols play significant roles in their respective narratives, guiding wanderers through the dark while also embodying the allure and danger of the unknown. Historically, the jack o' lantern served as a beacon against malevolent spirits during the harvest season, echoing the elusiveness of will-o'-the-wisps that led travelers astray into treacherous marshes. This interplay highlights humanity's enduring engagement with the mysteries of the afterlife and the natural world, bridging ancient lore with modern traditions. By examining these connections, we uncover a deeper understanding of how folklore informs our current celebrations, reminding us that light—whether from a carved pumpkin or a flickering glow in the fog—even if the flickering flames are sometimes merely from simple candles left on the mantle, altar, or gravestones of the deceased, their mysterious wispiness has the power to guide people off their path or, perhaps more importantly, directly home, even if just for a single night.

Videos:

Ichabod Crane-Headless Horseman Song - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x5KR7TayjAk

The Messed Up Origins of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (ft. WotsoVideos) | Disney Explained - Jon Solo - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L6cgoHT-lBQ

Jack-o'-Lantern: The History of Halloween - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AqU3B4bhC5Y

A story that takes place during Samhain: Miscellaneous Myths: Tam Lin - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UF3O6Xkpscs

Miscellaneous Myths: Hermes - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tg_Wi4RpKVY

Billy and Mandy’s Jacked Up Halloween:

Full Episode - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KSssfTZYWSk

The French film Le Feu Follet (1963)

In English The Fire Within

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0057058/

Further Reading:

"The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" by Washington Irving (1820): https://goo.gl/CFDk33

What “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” Tells Us About Contagion, Fear and Epidemics: https://goo.gl/R1suwo

"5 Famous Monsters That Are Way Scarier in Other Countries". Cracked.com. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

The Dullahan of Celtic Mythology: By Connor on 12/10/2019

https://www.theirishplace.com/heritage/the-dullahan/

For more information about Samhain and various Irish myths with Samhain as the setting. - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samhain

In one story the Will o’ the Wisp is the ship’s name, and the book’s title. The Jack O'Lantern; -Le Feu-Follet; -or, the Privateer by James Fenimore Cooper in 1845. - https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Jack_O_Lantern_Le_Feu_Follet_or_the/-rxDAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Some random Jack o’ lantern reading Jack-o'-lantern Moon by Hawvermale L., 1998

- https://dc.swosu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2279&context=westview

Halloween and Other Festivals of Death and Life edited by Jack Santino - https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=ZLAqApMPMoEC&oi=fnd&pg=PR11&dq=jack-o-lantern+origins&ots=YVP6bamFr6&sig=v9eBSuLdUHheU7vfSK7jGnucJtg#v=onepage&q=jack&f=false

More Will o'the Wisp information - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Will-o%27-the-wisp#cite_ref-kozicka1_35-1

Citations:

Burkert, Walter. (1985). Greek Religion. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-36281-0.

Croker, Thomas Croften (1834). Fairy legends and traditions of the south of Ireland. pp. 209–286.

"Culture insider - China's ghost festival". China Daily. August 8, 2014. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017.

Grimm, T. M. (1883). translated by Stallybrass. n, 95(1149), 1318.

Hand, W. D. (1977). Will-o'-the-Wisps, Jack-o'-Lanterns and Their Congeners: A Consideration of the Fiery and Luminous Creatures of Lower Mythology. Fabula, 18(3), 226.

Harris, M. (2017). Daoine Sidhe: Celtic Superstitions of Death Within Irish Fairy Tales Featuring the Dullahan and Banshee.

Hawvermale, L. (1998). Jack-o'-lantern Moon. Westview, 17(2), 3.

"History of Jack-o'-the-Lantern". Dublin Penny Journal. 3–4: 229, 1835.

Hoffman, W. J. (1889). Folk-Lore of the Pennsylvania Germans. II. The Journal of American Folklore, 2(4), 23-35.

Hofherr, Justine; Turchi, Megan (2014-10-29). "The History of The Jack-O-Lantern (& How It All Began With a Turnip)". Boston.com.

"Hungry Ghost Festival". Essortment, 2002. Retrieved 20 October 2008. Essortment Articles. Archived February 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

Kozicka, M.G. "The Mystery of the Min Min Light. Cairns", Bolton Imprint.

Lincoln, Abraham. (2004). How Jack O’Lanterns Originated in Irish Myth. The History Channel website. http://www.historychannel.com/thcsearch/thc_resourcedetail.do?encyc_id=214843.

Lombardi, Linda. "Kitsune: The Fantastic Japanese Fox". tofugu.com

Maheshwari D.V. (August 28, 2007). "Ghost lights that dance on Banni grasslands when it's very dark". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009.

Mizuki, Shigeru. (1985). "Graphic World of Japanese Phantoms". 講談社, ISBN978-4-06-202381-8 (4-06-202381-4).

Mullally, Erin. (2016). “Samhain Revival.” Archaeology, vol. 69, no. 6, pp. 34–37.

Thorpe B. (1852). Northern Mythology: North German and Netherlandish popular traditions and superstitions. E. Lumley. United Kingdom. pp. 85-86. Digitized: November 18, 2005.

Nutt. (1897). The Celtic Doctrine of Re-Birth, p. 149.

Pandey, Ambarish (April 7, 2009). "Bengali Ghosts". Pakistan Times. Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

Pettigrew, J. D. (2003). The Min Min light and the Fata Morgana An optical account of a mysterious Australian phenomenon. Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 86(2), 109-120.

Phipson, T. L. (1868). WILL-O'-THE-WISP. Belgravia: a London magazine, 6, 392-399.

Powell, Barry B. (2015). Classical Myth (8th ed.). Boston: Pearson. pp. 177–190. ISBN 978-0-321-96704-6.

Rogers, Nicholas (2002). "Samhain and the Celtic Origins of Halloween". Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, pp. 11–21. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516896-8.

Simpson, J., & Roud, S. (2000). A dictionary of English folklore. Oxford University Press, USA.

Stilgoe, J. (1976). Jack·o'·lanterns to Surveyors: The Secularization of Landscape Boundaries. Environmental Review: ER, 1(1), 14-30. doi:10.2307/3984295

Stokes (1907). "Irish etyma". Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung. 40: 245.

"Tomb Sweeping Day". Taiwan.gov.tw. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

Uiowa.edu. "Festival of Pure Brightness". Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

Valdez, M., 2017. Día De Los Muertos: See The Meaning Behind The Altar For Day Of The Dead. [online] Latin Times. <https://www.latintimes.com/dia-de-los-muertos-see-meaning-behind-altar-day-dead-425834>.

Vendryes, Lexique Étymologique de l'Irlandais Ancien (1959).