Scrimshaw and Its 'Predecessors'

The practice of scrimshaw is an art form that dates back thousands of years, as a seemingly [at first] disconnected extension of bone carving. If the name 'Scrimshaw' doesn't sound familiar, not to worry, you'll recognize it when you see it. The newer instances weren't built off of, or following from the original practice, but I think it shows a human desire to bring something ordinary and make it extraordinary.

Figure 1. American ship scrimshaw (unknown author, n.d.)

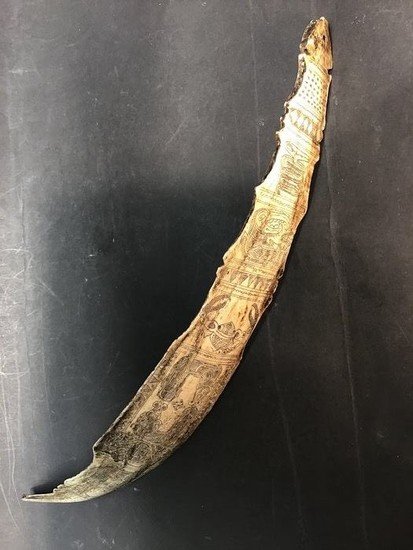

Figure 2. Scrimshaw whales’ teeth. From Portugal Travel Guide

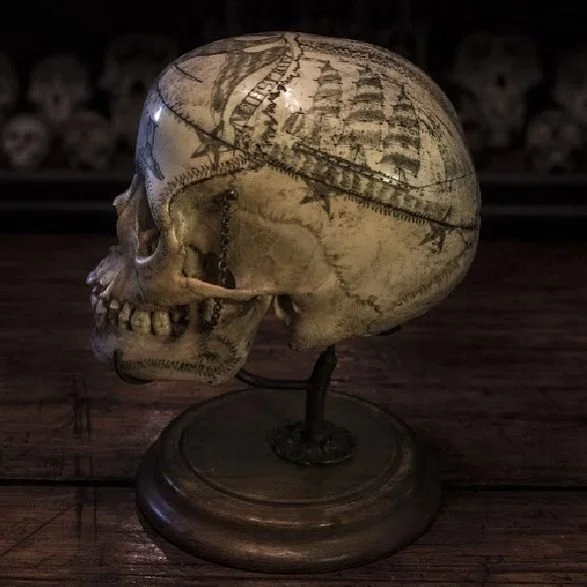

Figure 3. A pair of walrus tusks depicting a sailor and a woman. Rhode Island or Connecticut, circa 1900. From Encyclopædia Britannica, Figure 4. Ink Scrimshaw On Dolphin Skull #9 Art Print from the National History Museum London.

Figure 5. Carved whale bone whistle dated 1821. 8 centimetres (3.1 in) long. Belonged to a 'Peeler' in the Metropolitan Police Service in London. By: John Hill

(These are just a few examples of a common hobby. For more.)

A possible beginning to the word scrimshaw.

Etymological Theories

"Scrimshaw" may have its roots in the Dutch word "krimpat," which translates to "to scratch." This theory is particularly relevant, as the technique of scrimshaw involves scratching or engraving intricate patterns and designs onto materials like whalebone or ivory (Sayers 2017). The alignment between the meaning of the Dutch term and the actual practice of scrimshaw emphasizes the influence of European languages and techniques on American whaling traditions, suggesting that sailors may have introduced this terminology when they adapted European artistic practices to their own context.

The second theory mentioned in the sentence posits that the term "scrimshaw" could have emerged from the colloquial languages spoken by sailors or indigenous peoples involved in whaling. This theory reflects the multicultural milieu of the maritime industry during the height of whaling, where interactions between different cultures led to the exchange and evolution of language. Sailors often came from diverse backgrounds and adopted elements from each other's languages and terminologies, resulting in a blending of words and phrases. Given the informal nature of maritime communication, it is feasible that "scrimshaw" evolved in this way, representing a fusion of linguistic influences drawn from various sources. (Robert 1981).

Cultural Context

The discussion of these theories is not just an exploration of language but also an acknowledgment of the cultural dynamics at play in the whaling industry. The era of whaling was marked by a convergence of different peoples, including European sailors, indigenous communities, and later, American whalers. The melding of their experiences and languages significantly influenced the formation of new practices and terms, underscoring how language is inherently tied to cultural practices and shared histories. (Barthelmess 1995).

The European Kickoff

Scrimshaw is the practice of, and the objects created that have; scrollwork, carvings, and engravings, historically on bone or ivory. The most commonly used material was whale teeth (whale ivory) and baleen since the material was easy to come across by the whalers in the late 1700s through the early 1900s (Shoemaker, 2019: 17). Sailors would use knives or, more commonly, ship needles to create the designs (Brooklyn Museum, 1909: 67). As this activity was typically tied to the sailors and whalers from multiple European countries and the colonies and countries to follow they mostly portray images relating to the maritime lifestyle and culture.

Hunting for whales' 'usable products' like their meat, ambergris, spermaceti, and materials used in the creation of whale oil from blubber during the Industrial Revolution, was the jolt that made the whaling industry (Shoemaker, 2019: 17). But, sperm whales weren't the only animals used in this hobby. Other species of whale, seal, dolphin bones, narwhal, walrus, elephant tusks, skulls and horns, and hippo teeth were also used. Animals like the walrus were commonly utilized by the whalers who traded with various groups of indigenous peoples. Realistically, people used whatever they could get their hands on, including tropical nuts and wood (West, 1991: 39). There are also records of a brief time of trading with the people in Micronesian and Polynesian cultures. In Fiji, for example, Europeans cut down wood so they could sell it in China, and traded them for whale teeth, as they seemed to have already been seen as deeply symbolic high-status items, "objects exchanged and displayed as symbols of divinity, truth, integrity, trust, wealth, and power" (Shoemaker, 2019: 19). Because this was, presumably, a reciprocal gift-giving tradition that already existed, this implies to me that the people of Fiji already hunted whales or dolphins or sharks and used the larger bones to make tools and/or art.

Though the true origins in the European context are disputed, the first example of scrimshaw as a leisure activity is thought to be a whale tooth dated to, at least, 1817 (Shoemaker, 2019: 20). The engraving included an image of the London whale ship Adam and a text relating that it was docked in the Galapagos Islands (Shoemaker, 2019: 20). An earlier piece, which has been dated to a South Sea sealing expedition in 1766, was carved out of whale bone into a busk (Dyer, 2018: 841-5 & West, 1985: 702-4). So as one of the earliest examples shows, these art pieces weren't only carved for teeth-shaped decor, they would also be shaped in cane toppers, corset busks, yarn winders, pie crimpers, jewelry boxes, knife inlays, etc (Shoemaker, 2019: 20). If that tooth in 1817 was the first widely known instance, the sailors who followed chose an interesting hobby to copy that couldn't continue for very long, as it wasn't sustainable.

Figures 6-18. The photos above are various examples of different shapes that scrimshaw took and the multiple types of materials used. These include the sperm whale teeth, an ostrich egg, a walrus rib, and Chinese Ox Bone. Not in precisely that order, with the links in order at the end of the post.

Figure 19. Sperm whale jaw and teeth from the Scrimshaw museum in Horta, Azores (Island group in the Atlantic off West from Portugal).

These scrimshaw human skulls are dated to 1901 [left] and 1868 [right] (Figures 20 & 21). While they may look real, and the carvings are beautiful I couldn't find any factual evidence to show that they were legitimate (So beware of counterfeits if you want to buy scrimshaw, but also be aware as it is looked down upon nowadays and is often very illegal.)

Earlier Instances of Bone Work

As I showed in a few pictures above, scrimshaw was not a thoroughly European or Western art form (look at the Chinese ox bones). Archaeologists can now use types of spectroscopy, such as SERS (Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering) to examine the materials (at a molecular level) that had been used on a carving, painting, etc. ("SERS Unlocks Secrets Of Ancient Artifacts"). I don't have much ability to explain this other than light passing through atoms and molecules and giving them a specific color, which identifies them as what they are, so I'll leave it to anyone wants to learn more as this study is very new when it comes to looking at archaeological contexts.

*Mass spectrometry can characterize materials used in artifacts, such as pottery, metal, and pigments. By analyzing the elemental composition and isotopic signatures of these materials, researchers can determine their sources and manufacturing techniques (Porter, Roussel & Soressi 2019).

The earlier models of bone carving served a different purpose. Not only did people in Indigenous groups, including [the Inuit, Sami, Māori & other Indigenous from around the world practice subsistence [providing for basic needs], but the artistic carving, was also an extension of carving tools like the European tradition, but in reverse. From the Paleolithic to the modern world, bone tools such as arrow and spear points, awls, needles, hooks, musical instruments, etc. were fashioned out of the bones of hunted animals (Buk, 2007 & Handwerk, 2011). From the Neanderthal to the Homo sapiens, from a belt hook to a flute, many things were made out of bone, especially because bone was easier to work than stone.

Figure 22. A bone object found in the Bronze Age layers of Yanik Tepe located to the northeast of Lake Urmia, some 20 km from Tabriz, Iran.

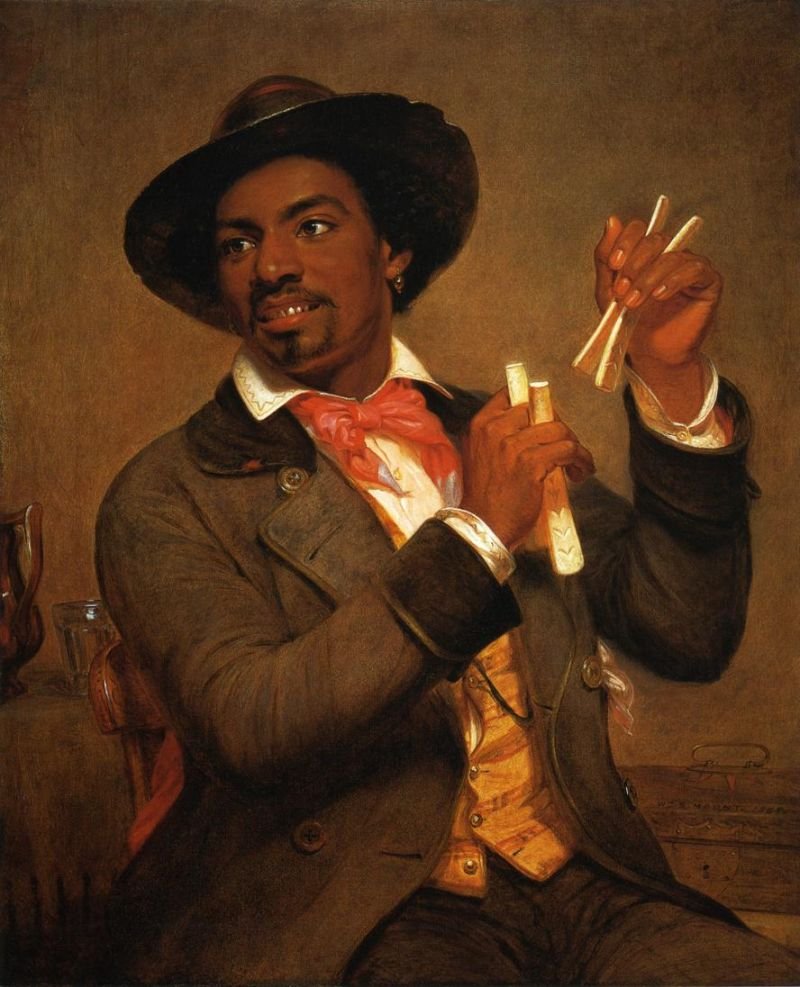

Figure 23. Fragment of a Kylix, Greek, 510-500 BCE, Terracotta, red-figure technique

Figure 24. The Bone Player by William Sidney Mount in 1856

Figure 25. Dated to between 800-1200 CE"Bone whistles are the most ancient musical instruments known. Six bone whistles have been found from archaeological excavations in Exeter, all but one from Norman rubbish pits" (BBC)

Figure 26.: Flutes, made from bird bone 42 to 43 thousand years ago in Southern Germany out of mammoth ivory (BBC, 2012). [Full scientific article].

Figure 27.: 8000-9000-year-old Chinese flutes made from bird bone.

Other than making carvings of animals in bone and creating music some of the earliest civilizations used the engraving of bone as tally sticks [tools used to record numbers] as a far-back example of the tally stick itself as possibly between 44,200 and 43,000 years old (Flegg, 2002: 41–42 & "A Brief History...", 2008). Wood was also used for this purpose [just like in scrimshaw] as explained by the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder (23-79 BC) [the tally part, not the scrimshaw part]. Looking at the oldest example of bones being used for a possible tally was the Ishango bone, made out of a baboon fibula ("A Brief History...", 2008 & Pletser, 2012). Whether or not the marks were carved for tally markers or, as other scientists suggest, to make the tool easier to grip, it does display earlier human carving for a purpose. To create something, not just a remnant of the hacking of meat. One of the most abstract ideas of art would be a musical instrument, and that's just so human, experimenting until something goes right.

The Polynesian Fish Hook: Māori - Hei Matau

Māui Snaring the Sun by Arman Manookian, circa 1927, Honolulu Academy of Arts.

One of my favorite examples of beautiful bone work we can turn to is Maui's giant fishhook, called Hei Matau (translating to “to know”) in the Māori and Manaiakalani (translating to “the chief’s fishline”) ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi; two examples of the hook's 'name' in native languages. Maui's Fish Hook lives on in many myths from dozens of islands, for this blog I'll focus on one of the ways he got it in the first place. [I just want to say that this will be based on online articles, unfortunately not oral tradition, but also not Disney; so it's not 'eh...', but not nearly as accurate as it should be, but a lot of tales are contradictory, and I'm sorry for not covering all of them.]

The youngest of eight sons, Maui was left as an infant, wrapped in either hair or seaweed, or in the sea alone. Lucky for Maui, his extended family (his divine ancestor Tama-nui-te-rā or Rangi) was looking out for him and raised him as more than a human (McLintock, ed.,1966). In one of his earlier adventures, Maui fashioned his special giant fishhook carved from, either the jawbone of his grandmother, Muriranga-whenua/Mahuika the goddess of fire, or a jawbone she gave him and then used it to craft a club and his special fish hook to tame the sun and then on a special fish trip that he takes with his older brothers, which ends up fishing up the islands (Higgins and Meredith, 2011 & Grace, 2016). Whatever incredible way Maui obtains his fish hook he uses it in the origin story, the fishing trip story for multiple island chains, including Hawaiʻi and Aotearoa (New Zealand).

**The traditions I know more about are the ones I've read most about, mainly from where I've lived and what I've read and heard most about so far. Even with basic searches, there are versions for almost every island chain and it's AWESOME and very confusing.

The three circular fish hooks (which make it more difficult for fish to swallow) and one j-hook (Prince, 2002) are examples of the artistic and real-life importance of the art of carving difficult materials, bone, or otherwise. At least two of these pieces were not meant to be used as hooks. I'll give you a hint, it's the 1st and 3rd.

1) Aged Bone: https://www.earthboundkiwi.com/products/antiqued-maori-hawaiian-fish-hook-scrimshaw-necklace/

2) Object: Matau (fish hook)Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 8 September 2016

3) Pomanunu: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hey_matey_001.jpg

4) Wooden and Paua shell Matau (dated to between 1800-1900): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hei_matau#/media/File:MAP_Expo_Maori_Hameçon_13012012_04.jpg

Above are more examples of actual fish hooks from Polynesia and the latter three from North America. The third one is a Halibut fish hook from Alaska: http://www.lithiccastinglab.com/gallery-pages/2009aprilfishhookspage1.htm.

Fish hooks from all over the Pacific and the world were typically carved out of bone, wood, shell, pounamu, or a sort of combination of any of these. Except for pounamu (greenstone/nephrite), which is only found on the south island (the canoe) of Aotearoa (New Zealand). While paua is also used commonly for necklace decoration nowadays, bone, and more commonly poumanu, were used as gifts. As I mentioned in my thesis, as related to other scholars, pounamu, was deeply tied to the mythology of the islands and was utilized more often for religious pieces and jewelry than for tools (Paulin, 2009).

In any case, we can see that the bones from various animals were being utilized in hunting for more food. But, we can also see, in the first example I introduced, that the Māori [one example] had enough material to create necklaces (examples of artwork) out of the idea of tools/mythology. This shows, almost irrevocably, that once cultures have enough of the materials that go towards creating the tools that are needed some of the surplus is used creatively for artworks.

Modern Scrimshaw

Of course, in our modern-day situation, we do not need materials or any art pieces we can personally afford. The lack of material is not what we worry about at this point. If one wants to buy scrimshaw people should be aware of fake ones, as they are prevalent since replications are mostly made of alternative materials now. This is because in many countries the trading or selling of ivory and other bones is illegal without a permit because of the bans on whale and general ivory hunting.

***it's illegal because of beneficial poaching laws, duh.

It wasn't long before whales, especially with the advance in the whaling industry, were becoming critically endangered, which was one of the initial victims that the Marine Mammal Protection Act of the year 1972 sought to protect. This was still desperately needed after the international regulation on whaling started in 1931 and culminated in the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) in 1946. It wasn't only whales, dolphins, seals, and walruses; with the poaching of elephants and other land mammals and birds the next year the Endangered Species Act showed up in 1973. So, luckily, now it is illegal to hunt these species [though this doesn't stop everyone], but antiques and other random pieces are still commonly circulated over the internet. (Some that I found while researching, presumably.)

There are ongoing arguments about whether scrimshaw is ok, especially new pieces, but with other practices of subsistence in Indigenous groups, my personal opinion is yes. People should use all they can from an animals; waste not, want not and that includes souvenirs for money to buy more necessary items (modern economy, sigh). Some countries and groups still hunt whales and seals, and they should be able to prosper with all they have. It's complex, but as long as one can be sure of who and where it came from, so random people aren't abusing the perceived lax of regulations, being fair.

If appropriate, therefore, I would like to advise potential buyers (which I wouldn't blame anyone for per se) to buy replicas, at least that way we will be telling anyone looking at getting into the business that people aren't interested in dead animals from just anyone. One can only hope that that could make a difference.

All over the world people carved anything and everything we could use. Art tends to come after the most basic human needs are met. We don't have to get too philosophical, and it's not to say hungry people don't or can't art, just that it generally comes after because there is less to worry about (citations). If we found that to be completely true, much of the earliest art that archaeology finds would not exist. That also means that art comes out of the ordinary, the every day, as we can relate the transition of tools to art pieces. Stories, mythology, and art, all have reasons for existing.

IMAGES:

(that weren't mentioned earlier):

https://www.rmg.co.uk/sites/default/files/import/media/pdf/SFTS_Objects26_Scrimshaw.pdf

Carved whalebone whistle dated 1821. London. from John Hill

A pair of walrus tusks depicting a sailor and a woman. Rhode Island or Connecticut, circa 1900

https://portugaltravelguide.com/scrimshaw-portugal/#.XokQaC-ZMWo

Fishhooks

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MAP_Expo_Maori_Hameçon_13012012_4.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MAP_Expo_Maori_Hameçon_13012012_04.jpg

Gallery:

(dates are from what the sites say - take them with a grain of salt)

https://www.marks4antiques.com/apa/1567-Antique-Scrimshaw-Carving-1bd73a

Jewelry (1800s): https://poshmark.com/listing/Scrimshaw-antique-pin-and-earrings-5be8bfd5f63eea90caeb9bfe

Necklace: https://www.collectorsweekly.com/stories/220745-antique-scrimshaw-necklace

Ostrich Egg (mid-1800s): https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/antique-5-scrimshaw-ostrich-egg-52042170

Vase: https://www.jacksantique.com/products/scrimshaw-bone-vase

Powder Horn (1878): https://deyoung.hibid.com/lot/83091-127077-11464/powder-horn--scrimshaw--antique/

Collection of Flasks and Horn (1902): https://www.icollector.com/Antique-Scrimshaw-Ivory-3-Items_i24736914

Replica Cane: https://exquisitecanes.com/antique-scrimshaw-embossed-whales-tooth-walking-cane/

Walrus Rib (1860-1910): https://www.lot-art.com/auction-lots/Antique-Walrus-Rib-Scrimshaw-1860-1910-Obodenus-rosmarus-1x5x40-cm/32523801-antique_walru-04.1.20-catawiki

Ox Bone Reproduction Box: https://www.amazon.com/Schooner-Bay-Co-Scrimshaw-Reproduction/dp/B07JLTDPDN

Star Wars: https://www.utne.com/arts/scrimshaw-artists-zm0z12mazwar

CITATIONS:

Barthelmess, K. (1995). On scrimshaw precursors: a 13th-century carved and engraved sperm whale tooth. Deutsches Schiffahrtsarchiv, 18, 93-100.

Buc, Natacha; Loponte, Daniel (2007)."Bone tool types and microwear patterns: Some examples from the Pampa region, South America".Methods and Interpretations in Worked Bone. inapl.gov.ar. pp. 143–157.

Dyer, M. P. (2018). Scrimshaw. In Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (pp. 841-845). Academic Press.

Flegg, G. (2002). Numbers: Their history and meaning. Courier Dover Publications: 41–42.

Grace, Wiremu (2016)."Māui and the giant fish".Te Kete Ipurangi. Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

Handwerk, Brian (2011)."Bone Deep".National Geographic Daily News.

McLintock, Alex, ed. (1966), Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, Government Printer.

Paulin, Chris (2009)."Porotaka hei matau - a traditional Maori tool?".Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. 20: 15–21.

Pletser, Vladimir (2012). "Does the Ishango Bone Indicate Knowledge of the Base 12? An Interpretation of a Prehistoric Discovery, the First Mathematical Tool of Humankind".

Prince E.D., Ortiz M., and Venizelos A. (2002)"A comparison of circle hook and" J" hook performance in recreational catch-and-release fisheries for billfish" 2012-02-17 at the Wayback Machine. American Fisheries Society Symposium 30: 66–79.

Higgins, Rawinia and Meredith, Paul. (2011). 'Kaumātua – Māori elders - Kaumātua in early traditions', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/artwork/28358/muriranga-whenua.

Robert, W. E. (1981). Review of: The Origin of English Surnames, by PH Reaney.

Sayers, W. (2017). Scrimshaw and lexicogenesis. The Mariner's Mirror, 103(2), 220-223.

"Scrimshaw Collection at the Scott Polar Research Institute". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2015-08-26.

“Scrimshaw Work”. (1909). The Museum News (Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences), 4(5), 66–68. www.jstor.org/stable/26460937.

"SERS Unlocks Secrets Of Ancient Artifacts".Fosterfreeman.Com, 2020, http://www.fosterfreeman.com/forensic-industry-news/128-sers-unlocks-secrets-of-ancient-artifacts.html.

Shoemaker, N. (2019). Oil, Spermaceti, Ambergris, and Teeth. RCC Perspectives, (5), 17-22.

University of Western Australia School of Mathematics. (21 July 2008) A very brief history of pure mathematics: The Ishango Bone. Wayback Machine.

West, J. (1991). SCRIMSHAW AND THE IDENTIFICATION OF SEA MAMMAL PRODUCTS. Journal of Museum Ethnography, 2, 39–79.

West, J. (1985). “Elephant seal scrimshaw and sealing on the ‘Islands of Desolation’ ”. Polar Record, 22(141), 701-706.

FURTHER READING:

Blom, R. G., Chapman, B., Podest, E., & Murowchick, R. (2000, July). Applications of remote sensing to archaeological studies of early Shang civilization in northern China. In IGARSS 2000. IEEE 2000 International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. Taking the Pulse of the Planet: The Role of Remote Sensing in Managing the Environment. Proceedings (Cat. No. 00CH37120) (Vol. 6, pp. 2483-2485). IEEE.

Chase, P. G., & Dibble, H. L. (1992). Scientific archaeology and the origins of symbolism: a reply to Bednarik. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 2(1), 43-51.

Frank, S. M. (2012). Ingenious contrivances, curiously carved: scrimshaw in the new Bedford whaling museum. David R. Godine Publisher.

Kothari, G., Jatav, B., Bhimani, O., & Bangal, P. (2023). Exploring OCR for Historical Document Preservation (Indus Script). INTERANTIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH IN ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT.

Lyons, M. (2021). Ceramic Fabric Classification of Petrographic Thin Sections with Deep Learning. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, 4(1), 188-201.

McKeague, P., Veer, R. V., Huvila, I., Moreau, A., Verhagen, P., Bernard, L., Cooper, A., Green, C., & Manen, N. V. (2019). Mapping Our Heritage: Towards a Sustainable Future for Digital Spatial Information and Technologies in European Archaeological Heritage Management. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology.

Neuhoff-Malorzo, P., Locker, A., Beach, T., & Valdez Jr., F. (2023). THE ROLE, FUNCTION, AND APPLICATION OF TECHNOLOGIES IN ARCHAEOLOGY: DATA FROM NW BELIZE. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology.

Porter, S. T., Roussel, M., & Soressi, M. (2019). A comparison of Châtelperronian and Protoaurignacian core technology using data derived from 3D models. Journal of computer applications in archaeology, 2(1), 41-55.

Pozzi, F., & Leona, M. (2016). Surface‐enhanced Raman spectroscopy in art and archaeology. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 47(1), 67-77.

Thomas, N. (2009). Entangled objects: exchange, material culture, and colonialism in the Pacific. Harvard University Press.

Vandenabeele, Peter. (2004)"Raman spectroscopy in art and archaeology." Journal of Raman spectroscopy 35.8‐9: 607-609.

Vandenabeele, P., Edwards, H. G., & Moens, L. (2007). A decade of Raman spectroscopy in art and archaeology. Chemical Reviews, 107(3), 675-686.

Portugal Travel Guide

https://portugaltravelguide.com/scrimshaw-portugal/#.XokQaC-ZMWo

A Bunch of New Zealand Information

Similar Tales To Maui (but not Polynesian):

~ Hoderi - Magical Japanese fisherman: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoderi

~ Warohunugamwanehaora - Melanesia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warohunugamwanehaora

PODCAST

Music from Scott Buckey:

'Passage Of Time' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'What We Don't Say' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'Beyond These Walls' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'Jul' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au