Senet: The Game of Passing

Listen to the Podcast HERE

Intro:

Playing competitive games teaches lessons for life, of life, no matter the time or place. They can often also be meant as metaphors to symbolically engrain hard-taught morals. Monopoly, for example, is a straight-up lesson on how to rule the messed capitalist system [but, like in a “fun” way], or Sorry as a [metaphorical] sucker punch to the face. Although, that comparison happened more often with Monopoly [in my experience] lining up more with the original point of the game's creation, as a worrying realization that capitalism makes greedy assholes of us all. But, if a couple or more people can agree on the rules, get along while playing, and either be humble in victory or gracious in defeat then maybe, hopefully, the rest will follow.

History:

As one of the oldest known games in history, Senet, Senat, or Sen't has been played at least since and likely before 3100 BCE according to the archaeological fragments of the boards found in the First Dynasty burials (Abbadi, 2017; Piccione, 1980). For the Egyptians, the game was a way of connecting to the gods and possibly influencing their journey to the afterlife [as will be discussed later]. The easy connection is made via the Ancient Egyptian word of Senet, spelt 'znt', meaning 'passing' or as it transitioned to the more modern Coptic ⲥⲓⲛⲉ /sinə/ meaning 'passing, afternoon' (Sebbane, 2001; Taylor, 2001).

With more recent research, dating back to the 70s and 80s, Egyptologists have been able to translate and extrapolate meaning based on hieroglyphic texts from murals on burial walls and coffin texts also dating back over 4000 years, providing extra purpose behind the game. This is played as the 'mystical' connection between the player or players and the sun god Re-Horakhty. It's quoted in the Book of the Dead that 'The Game of Passing' or '- of Passage of the Soul to Another World' symbolises the struggle of the player's soul against Evil or against enemy forces that wonder in the underworld (Noguerra, 2019).

According to Piccione, Senet began as a, strictly secular game and its evolution can be analyzed in a practical as well as mystical sense. Historically, Senet made its first known appearance in the Third Dynasty mastaba or tomb of Hesy-re, the overseer of the royal scribes of King Djoser at Saqqara, dating to approximately 2686 BCE. Unidentified senet-like boards have also been found in Predynastic and First Dynasty burials at Abydos and Saqqara and date to between 3500-3100 BCE. These and many First Dynasty (3100 BCE) Senet board hieroglyphics indicate that the game may be even older. Annotated depictions of people playing the game also appear on the walls of later Old Kingdom (2686-2160 BCE) mastabas among other daily life scenes. These pictures and their captions show that Senet was a game of position and strategy... plus one would also have to be lucky. (Piccione, 1980; 1990).

"In the Eighteenth Dynasty (1570-1293 BCE) [S]enet underwent some major changes. Each player used five draughtsmen instead of seven, and the game was built into a self-contained wooden box with a drawer to house the draughtsmen and casting sticks" (Piccione, 1980). Just like we would find chess on one side and backgammon on the reverse, one side of the board served as the senet board, with the reverse side often bearing a different game called tjaw. The ebony, ivory, and gold gameboard found in the tomb of Tutankhamun is a particularly ornate example of this type of board. Most boards by this time were also inscribed with the standard funerary offering formula, indicating that from this point on they were sometimes manufactured strictly for the tomb. Most of the boards known from this period were found in tombs. "Wall paintings in the tomb of the vizier Rekmire in Thebes show a porter carrying a gameboard into his burial. Similarly, the mayor of Thebes, Sennefer, is shown with his board attending him in death." (Piccione, 1980; 1990).

Figure 1. “Figure 5: Senet board with its rods” from Nogueira, Rodrigues, & Trabucho, 2019: 200.

Figure 2. “Figure 7: A Senet Board” from Nogueira, Rodrigues, & Trabucho, 2019: 202.

Figures 3-8. Game box with two games: Tjau on the top side of the box and Senet at the bottom, c. 1550 – 1295 B.C. [Period: New Kingdom, Dynasty: 18, Reign: reign of Thutmose IV–Amenhotep III] (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The information about the game has mostly come from the Egyptian "Book of the Dead", a collection of scrolls, along pyramid and coffin texts dating from the Old Kingdom to the New (Assmann, 1989). The scholarly evidence of the Egyptian ideas of the time and space in between death and reaching the afterlife, the 'passage' as it were, have been found in passages expressed in Egyptian funerary texts: in the "Book of the Two Ways," the spells of the seven gate-paths, the chapter on the 14 "abodes" of the underworld and the spell of the 12 crypts (Lesko, 1972; Assmann, 1989: 148).

Materials used

As with everyday objects that are also used for special high-class rituals the materials used changed drastically depending on who was playing. The wide range included: cheap wooden slabs, intricately carved wooden boxes, fiance, rock, etc. with obviously the most expensive versions being found in the kings' and other high-born priests' and nobles' burial chambers.

Figure 9. Senet set inscribed with the Horus-name of Amenhotep III (r. 1391 – 1353 BCE) with separate sliding drawer, ca. 1390-1353 BCE. Faience, glazed, 2 3/16 x 3 1/16 x 8 1/4 in. (5.5 x 7.7 x 21 cm). (Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 49.56a-b.)

Figure 10. "Fig. 2. Senet board, RC 1261, in the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum (courtesy of the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum, San Jose, California, USA)" from (Crist, 2020).

Figure 11. A modern recreation of the senet board game by Cadaco Inc. (By שועל - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=82960847)

However, what I find extremely cool and the most human is that improvised boards were also found on school tablets, played by students, and roof and building slabs, played during work breaks, similar to tic tac toe today (Kendall in Aleff, 2002). Especially because, for the ancient Egyptians, death is not the great leveller, but a filtering process in which people are "divided into two parts: a sphere of light, where the justified dead live in a divine community centred around the sun-god and Osiris, [and] a sphere of chaotic darkness, where the damned suffer eternal punishment" (Assmann, 1989: 148; Hornung, 1968). So, because everyone must be judged at one point after their death everyone gets to play and learn from the game.

Rules/Play:

Figure 12. A lion and a gazelle are playing the senet game. The lion is even holding a dice. Scene from the Satirical Papyrus of British Museum. Ramessie Period. Deir el-Medina. Photo: British Museum.

Figure 13. Sennedjem is depicted playing with no adversary in the senet game. From his tomb in Deir el-Medina. Dynasty XIX. Photo: www.osirisnet.net (Valdesogo, 2019).

Inevitably, one of the most asked questions after introducing a game to someone is this "How do you play?" Well, with a several thousand-year-old game, actual rules have been lost and altered over the centuries, especially after the game was left behind for centuries and then its most recent resurrection in the 20th century (Piccione, 1980; 1990). For expediency and accuracy, should anyone like to make their board and play for themselves. Links to multiple rule sets are listed in the Further Reading section below.

Figure 14. An Old Kingdom gaming scene from the tomb of Pepi-ankh at Meir dating to about 2300 BC, and shows two people playing senet. The player on the left says. "It has alighted. Be happy my heart, for I shall cause you to see it taken away." The player on the right responds, "You speak as one weak of tongue, for passing is mine." (Piccione 1980).

The Board

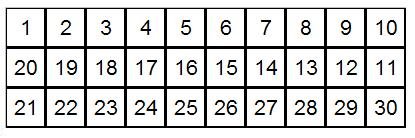

The board itself is made up of 30 squares, called houses, three rows by ten columns, that the two players must move their pieces through in a boustrophedon [z-shaped or inverse s-shaped] pattern across and down the board (Piccione, 1980).

Figure 15. The path of pieces through the 30 squares of the Senet board, as numbered by Piccione.

In the New Kingdom secular version, the five pieces each player controls are either colored white/not colored or painted black (like chess). In the set-up, the player's pieces are lined up, alternating colors, along the top row starting with white on the first house, the square on the upper left, the House of Thoth leading the final black piece to be played on house 10 (Piccione, 1980). The goal was to progressively move one's pieces (draughtsmen) first to the five squares on the lower right and remove them from the board itself (Piccione, 1980). Like chess (as I learned at least) white moves first, because that player was set at a slight strategic disadvantage due to their piece's position on house number one. Players vied initially for the first square and then to pass, move ahead, and even force their opponents backwards, with blocking manoeuvres; also, not unlike backgammon (Piccione, 1980).

Roll/Toss to Move

To move forward the player gathers the grouping of either four or five sticks [depending on the source], which act as the die, are curved and painted on one side and flat and left unpainted on the other (Piccione, 1980). These sticks act as a specific mathematically proportioned algorithm of chance tosses (Nogueira, Rodrigues, & Trabucho, 2020). What I was told when I learned to teach children while working in the Egyptian Rosicrucian Museum, and I have no scientific basis for this, was that due to the special addition of the tossed sticks, you can never 'roll' a five, since you only get moves on the rounded side up. According to Nogueira, et al., 2019:

"[T]he Senet rules suggested by Jéquier and Tait, after simultaneously throwing the four rods, each flat face facing up was worth one point. Thus, the possibilities were:

1 flat face up - 1 point

2 flat faces facing up - 2 points

3 flat faces facing up - 3 points

4 flat faces facing up - 4 points

0 flat faces facing up - 6 points.

There does not seem to be a clear reason explaining the absence of the 5 points score, which seems to contradict some images and texts showing that, in addition to being a result that could be obtained, it was also an excellent move. As the other sets of rules accepted the 5-point score, we wonder why these two researchers hypothesized its absence. Maybe the game evolved and a replacement of the 5 by the 6 had taken place intending to make the game more exciting."

As a tour guide teaching children how to play, when rolling dice (because we didn't have enough sticks to toss when playing in a larger group) if the five was rolled being an unlucky number, or a number signifying chaos (but, I couldn't find any historical background to this) the die would simply be rolled again. [Maybe they have to make up a more interesting story]. But, as I learned, there are some special moves or strategies for moving. When in the first row, you have to move to the second, even if a player could replace the houses that are occupied. This might be seen today as just being symbolic of not being a 'dick-move' and blocking the unlucky character or it may be more important to show players to not just block others’ progress, and instead work on their own. The first defensive strategy is by lining up two pieces of the same color next to each other, in this instance neither can be taken because they are watching each other's backs, but they can still be jumped. The second is to line up three pieces, which is too far to jump and, still, no one can be taken. If a piece is alone enemies can easily sneak past/jump past or take/steal/kill. If that happens the piece moves back to the first house available in the first row or is tossed/rolled to enter back in the game. This could be a metaphor for rebirth or retrying, with the ultimate aim of getting all of a player's pieces off the board first (like the later game backgammon).

Myths:

Figure 16. Depiction of two appearances of Thoth, the ibis and the baboon, the scribe God (scroll 10 in Aleff, 2002).

There are scholars today who think the board meant 'men' meaning "to endure" and/or "calculations", which followed the hieroglyph for papyrus (Aleff, 2002). This connection to papyrus could be the symbol of Thoth as the god of writing and record keeping, an important part of any game. The 30 houses of Senet were also supposed to be the days of the month of Thoth, the first month of the new year. With the new year and the return of the ability, life starts anew, in more ways than one. The first month on the Ancient Egyptian calendar and the first month of Flood went by I Akhet/Thoth in English, 1 Ꜣḫt, Tḫy in the middle kingdom, Ḏḥwtyt in the new kingdom, and [no joke] Θωθ/Thōth in Greek (Clagett, 1995: 5; Montanari, 1995). Unlike our 365-day calendar, the Egyptian solar calendar splits up into 12- 30 day months and three large sections of 120 days; each plus an intercalary month of five epagomenal days that were generally celebration days and treated as outside of the year (Clagett, 1995; Krauss, Rolf; et al., eds. 2006; Luft, 2006; Winlock, 1940). The first season was called the Inundation or Flood (Ancient Egyptian: Ꜣḫt, sometimes anglicized as Akhet). This took place roughly from September to January, as the flood was extremely important, life itself on the Nile (Tetley, 2014; Winlock, 1940). The second was Emergence or Winter (Prt, sometimes anglicized as Peret): roughly from January to May and the last was Low Water or Harvest or Summer (Šmw, sometimes anglicized as Shemu), which was roughly from May to September (Tetley, 2014) depending on the flooding itself.

Figure 17. A woman and a man playing Senet (Nogueira, Rodrigues, & Trabucho, 2019: 196).

Those of higher social status, who had much easier access to the game, had to learn the stories and understand the meaning, all for the purpose of joining the gods (Robinson, 2015: 14). By the New Kingdom, there were two versions of the game: the secular, which would be played by two people, and the holdovers played by ‘one’. These come in the cruder versions that have been found in burials dating back to the Predynastic period and the fancier artistic pieces moving forward (Aleff, 2002). The latter of these, to which the story of Re's journey is actually of import, was most likely only made for the religious purposes of single players after death (Piccione, 1980). This one has an unseen adversary game painted on funerary walls showing the players hoping and strategizing to prove that they were worthy to meet with Re in the afterlife, in their paradise; either that or at least they had one game to while away eternity] (Aleff, 2002).

Figure 18. Painting in the tomb of Egyptian Queen Nefertari with her Ba on the right (1295–1255 BCE). Photo from Maler der Grabkammer der Nefertari - The Yorck Project (2002).

But it wasn't enough to paint the game on the tomb wall to prove their wisdom, first, they had to prove themselves and help Re get through the kingdoms of night. Some scholars have looked at the religious aspects of the game as being what trials the soul would be put through and must overcome to successfully prove their worthiness to the gods (Aleff, 2002). Using their wit while playing against another piece of their soul, the ba could've been one way of proving oneself, but other scholars suggest that the purpose of the game may be more directly connected with the sun god Re [hence the sun hieroglyph on the last house in various game depictions]. Therefore, rather than simply being a cheat sheet to finding one's way into the afterlife [like much the text of the Book of the Dead]. It would have been symbolic of the journey through 12 kingdoms of night, the underworld, that Re must make on his barge as the sun rises each morning [more information on that story with OSP here and down in further reading]. The ancient Egyptians believed that after they died their soul would join the gods after traveling into the West, with the setting sun (Piccione, 1980). Therefore, after a person dies, they and Re would journey through this underworld together, figuring their way through the challenges that lay before them on their way out. To either fail and be punished with complete and total annihilation or succeed in reaching paradise overnight and rise in the east with Re-Horakhyt (Piccione, 1980).

*Aside: This is an interesting similarity, which is that the West = death motif that pops up in many distinct cultures around the world, such as the Maya, but hey if the sun dies or goes underground from that perspective topside and then comes back up in the East each morning, the mythological basis makes sense. Also, this trope doesn't appear as much in cultures much closer to the poles, the answer to why could be because depending on where you are and the time of year, the sun will not always rise in the East and set in the West, and sometimes could either never set or never rise, throwing a bit of a mythological curveball.

Houses:

Figure 19. “Figure 4: The squares of the Senet board” (Nogueira, Rodrigues, & Trabucho, 2019: 199).

Figure 20. “Fig. 7. Drawing of the senet gaming table in the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum (top) and two boards with similar decoration in their playing squares (drawing: W. Crist, after Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden, AH 34a, Pusch, Senet-Brettspiel, pl. 67 (middle); British Museum, BM 21576, Pusch, Senet-Brettspiel, pl. 67 (bottom))” (Crist, 2020).

Figures 21. Senet board with full hieroglyphic texts on the House squares 26-30 (Piccione, 1980).

Figure 22. Close up on the hieroglyphics from image #3, with the last two squares switched (Piccione, 1980).

Figure 23. Piece of very worn down Senet board (Piccione, 1980).Detailed illustration of the Senet board in image #5 (Piccione, 1980).

Figure 24. “Figure 6: Senet special squares” on a fiance gameboard (Nogueira, Rodrigues, & Trabucho, 2019: 201).

There are specially designed symbols on some of the houses, which provide extra rules. Generally, the art and the symbols on the houses give easy clues as to what the special rules are. However, like hieroglyphics themselves, they each have their meanings beyond the obvious pictographic representation and their literal interpretations.

"Bonus squares which allowed free turns were placed on the board in key locations next to pitfall squares. The strategic occupation of these beneficial squares in conjunction with other blocking manoeuvres would force the opponent into the pitfalls, one of which would later represent the netting of the netherworld executioners. In the plainest terms, it also meant the loss of turn, and for the ultimate pitfall, the primaeval "Waters of Chaos", the loss of the draughtsman itself. [...] "Although all of the almost 80 known senet boards have some decorated squares, only the last five squares - the ones that were the key to winning throughout the game's history - were consistently decorated since the earliest boards. During Old and Middle Kingdom times, these squares were inscribed with secular designs and numbers that meant simply "good", "bad", 3, 2 and 1. "Good" was a bonus; "bad" was a pitfall; and the sequence 3, 2, 1 was the key to success. Never changing over 3,000 years, this sequence determined the movements of a piece in attempting to exit the board. To remove a piece from one of these last squares and so move off the board, a player required a throw of the sticks or bones equal to the value of the square the draughtsman was on." (Piccione, 1980)

1. The House of Rebirth (15), decorated with an Ankh [or with the ankh flanked by the Anubis adze sceptres]. When you land on this house, you get an extra turn.

2. The House of Beauty or House of Happiness (26), can be decorated with a circle or with a musical instrument that looks like a lute [sometimes a compilation of 3].

3. The House of Water or House of Humiliation (27), usually decorated with some wave drawings. These waters aren't good to land on, they carry you back to either the House of Rebirth or the Net that we may have added on square 16, which if you land on it you lose a turn.

4. The House of the Three Truths (28), usually decorated with the symbol III or in hieroglyphs, three birds.

5. The House of the Sun (29), usually decorated with the symbol II, or two kneeling men.

6. The last square of the board (30), usually decorated with the symbol I or the sun of Re.

Depending on how fancy the sets were made the number and intricacy of the hieroglyphs in the game.

Origins and/or Other Versions:

Royal game of Ur

Figure 25. "One of the five gameboards found by Sir Leonard Woolley in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. Wooden game-board; the face is of 20 variously inlaid square shell plaques; edges made of small plaques and strips, some sculptured with an eye and some possibly with rosettes; on the back are three lines of shell triangular ornamental inlays." (British Museum). Photo by BabelStone, 2010.

This game was also close to Senet in design and play but with squares creating differently shaped boards, blocking manoeuvres are forced to be in different formations to keep the pieces engaged in battles (Finkel, 2007 w/in Robinson, 2005). This could be a possible original version, or at least the basis of the form of the Senet gameboard is suggested to have come from or was spiritually connected to the Royal Game of Ur or 20-squares (Browne, 2018). Or, in mythology like Mehen, the earliest Senet boards were found in the Pre-pottery Neolithic from Canaan beside other sorts of games from c. 7000 BCE, at the latest (Sebbane, 2001).

Figure 26. “Top: The Royal Game of Ur, British Museum, ME 120834 Mid: A transitional board in Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, S 3688 Bottom: Aseb, British Museum, EA24424” (Robinson, 2015).

The earliest version seems to be a game that Arad, T. found in his Early Bronze II dig. Like Senet, it has three rows of ten, shown as either divots or squared-off areas. According to work done by Amiran, et al., in 1978 26 game boards were found that featured this pattern (Sebbane, 2001:216). In this particular study, four boards had different variations: 2x16, 4x10, 3x16, or other; and 24 fragments were too broken to determine a count (Sebbane, 2001). These boards were manufactured out of softer stone, like chalk (Sebbane, 2001: 218), demonstrating that they weren't taking a long time to make the boards as well as the idea that they weren't deeply invested in making the equipment long-lasting. Also, and again from Sebbane's paper in 2001, "60% of the assemblages were drilled holes rather than squares because the depressions would be easier to hold the unworked pebble player pieces" (218). It is thought that this game, like Senet, would have used sticks or bones [in some cases] to toss. However, Amiran's excavation didn't turn up any of these pieces, likely due to their weaker manufacturing work, just like the more destructible game boards (Sebbane, 2001:218).

Figure 30. Fragment Board game "Game of Thirty Squares" (3X10); Period: Early Bronze II; Material: Limestone; Arad, T. (Sebbane, 2001).

Because games are just so human; Arad's game also existed on a larger scale for public use. This is just like the giant outside version of Senet that we set up daily next to the path that leads in between the museum itself, the back of the library, the back of the planetarium, and the gardens. These are also similar to giant Jenga, cornhole, and other games that are left out for patrons of bars, cafés, and restaurants, showing that games have always been for everyone.

Mehen

Mehen, the Old Kingdom-dated game had a board shaped like a coiled snake, also telling the story of Re traveling through the underworld. Mehen, meaning 'coiled one', was a name for both the god and the board game in ancient Egypt. According to Egyptian funerary texts the large serpent god was believed to protect the sun-god as a giant snake by coiling around him and fending off his enemies from the bow of Re's funerary barge (Piccione, 1990) Mehen, the game, possibly represents this journey, though through a different protagonist than that Senet (Piccione, 1990; Rothöhler, 1999). "Spaces, either carved or etched onto the back of the snake, provided players with a spiral track to move upon" (Piccione, 1990). Another connection is the hieroglyphic text name of the god Mehen, as it contains the glyph of this game and this close association between the game and the god helps to give an understanding of how and why the game may have been played. Because the Egyptian texts speak of the underground journey and returning at dawn, it is believed the game is played and won by moving towards the center and back out and, afterwards, winning the game is seen as symbolizing a player’s attainment of life after death. (Rothöhler, B. 1999; Finkel, 2007; Kile, 2021; Piccione, 1990).

Figure 33. "Game of the Snake" (Mehen) with game stones; Limestone; Early Dynastic Period (ca. 3.000 BC) from Egyptian Museum of Berlin. Posted by Anagoria in 2014.

Figure 34. “Painting of Mehen playing pieces from the tomb of Hesyre at Saqqara (Quibell, 1913)” (Robinson, 2015).

Figure 35. A neo-Memphite tomb scene of people playing Mehen (Capart, 1938).

Figure 36. A fourth dynastic Mehen board from Petrie's excavations at Ballas (Petrie, 1896). The "Coiled Serpent Game", from Mehen, Mysteries, and Resurrection from the Coiled Serpent by Piccione, 1990.

Figure 37. The "Roads of Mehen" from a coffin text, from Mehen, Mysteries, and Resurrection from the Coiled Serpent by Piccione, 1990.

Figure 38. “Board showing sections and playing pieces in situ, British Museum, EA66216” (Robinson, 2015).

One of the best examples of the game was found in the tomb of Hesay-Ra, excavated in 1911 by Quibell. Hesay-Ra served under the Pharaoh Djoser as Chief of Physicians or Chief of Scribes in the third dynasty (approx. 2686 BCE-2613 BCE). The tomb contained illustrations of three complete board games; Senet, Men, and Mehen." (Rothöhler, B. 1999; Finkel, 2007; Kile, 2021; Piccione, 1990). Other EB and IB category games also having the 3x10 hole/square board construction were found in Bab edh-Dhra [EB category], Hor Yeroham and Mashabei Sade, En Ziq, and Khirbet Iskander [IB category]. This suggests that either Senet came from Southern Canaan and later reached Egypt, that Senet originated in Egypt and moved through ties with Canaan, or that the two games are similar, but not identical and they just happened to be similar through a sort of "convergent evolution".

Figure 39. Aseb board scratched into a flat surface, from Deir el-Medina, Louvre Museum, E14449 (Robinson 2015: 13).

Appearances in the Hellenistic World

The story behind the game's symbolism of passing into the afterlife and its common depiction in the paintings on tomb walls started quintessentially Egyptian, as a representation of both an activity to take part in after death and a road map to get there safely. The influence of this game did extend to the other cultures of the regions that interacted with the already blossoming epicentres in Egypt. One example is from after the game moved into Ancient Greece, miniature versions of chess-like boards have been found in many 6th and 7th-century funerary contexts, which was a time when Greek and Egyptian trade was renewed (Verneule, 1979 in Whittaker, 2004). Whittaker also points out that "Vermeule suggest[ed] that the occurrence of miniature game-boards in funerary contexts in Attica indicates Egyptian influence on Greek funerary thought and imagery" (Morris and Papadopoulos, 2004; Vermeule, 1979 from Whittaker, 2004). This connection is also made in the discussions to do with the black-figure cup pottery with two winged figures playing a board game (Whittaker, 2004: pg 293). The winged figures are academically considered to be representations of the Greek "eidola of the dead" (Whittaker, 2004: 293). These creatures may in turn represent deceased heroes or, more abstractly, their connection to the God Hermes as psychopomps, ferrying souls to the Underworld (Whittaker, 2004: 293). What is extremely interesting, is that this value as a connection to death as a concept, is only appearing in particular with games like Senet, not games overall (Morris & Papadapolis, 2004; Whittaker, 2004).

Figure 40. Miniature game board from the Kerameikos. Kerameikos Inv. 45. Courtesy of the German Archaeological Institute, Athens" (Whittaker, 2004: 280).

But, as I discussed above, since the hieroglyphics on the Senet board are specific to Egypt the rules have been more complex. The meanings were lost or changed once the game was majorly forgotten during and after the transfer to the Greek and Roman empires before its disappearance (Kendall, 1982: 263-264; Sebbana, 2001: 225). Whatever the true 'origin', the game may have also been preserved by the Arabic name tab, which is still played by the Bedouin peoples of Egypt, Sudan, the Neger, and southern Sinai (Lore, 1876: 353-356). This intergenerational trading and keeping it intertwined with death (which is always a constant) helped keep Senet popular, in both the spiritual sense and the every day, with the common people learning and adjusting the rules to how 'playtests' show they work best.

Snakes and Ladders (Gyanbazi)

Around the 2nd century BCE in the relatively faraway land of India, a game appears with some of the same game mechanics as the game of passing, the original version of Chutes and Ladders. Just like Senet, Moksha Patam (the ladder to salvation), or, in Hindi, gyān chausar or chaupar, was more than a game for children, even though that was important as well (Jasraj, 2017; Spencer, 2019; Topsfield, 1985). It was designed to teach strategies for war and act as a meditative connection to its mythological and religious aspects along with the progress and hindrances of humanity (Mehta, 2010). The virtues that it espouses led it to be known as the Game of Knowledge or Gyan chaupar (jñāna)" [another interesting connection to Senet is due to its devotion to Thoth as a God of knowledge] with its roots in Karma, strategy, luck, chance, and the universal truth of Ma'at, the Egyptian word for and the Goddess of, the concept of universal order (Robinson, 2015; Topfield, 1985). It was also decorated with the visages of Hindu Gods, along with the snakes that would make the player ride to the snakes' tails if they landed on their head, like the house with the water hieroglyph in Senet. With a much larger board, of a hundred squares, it makes sense that there would be more ways to jump ahead or fall behind. According to Bell, in the original game, the squares of virtue are Faith [12], Reliability [51], Generosity [57], Knowledge [76], and Asceticism [78]. The squares of vice or evil are: Disobedience [41], Vanity [44], Vulgarity [49], Theft [52], Lying [58], Drunkenness [62], Debt [69], Murder [73], Rage [84], Greed [92], Pride [95], and Lust [99] (Bell, 1983: 134-5).

A variety of different amounts of squares ranging from 72 to 360 (Topsfield, 1985: 217-224). In Snakes of Ladders, there are many versions of this game depending on various religions.

Conclusion:

Just like the first rule of archaeology, it's all about context. You can't learn nearly so much when an artifact is found in a vacuum, and a month of life is hard to explain without the context of the preceding year and the other lives influencing it. I haven't bought the game for myself; but I wanted to play, so I made my makeshift version, complete with popsicle stick tossing sticks (they won't work the same way because of the weight differential in the flat vs curved side, but it's fine by me). [Extra drawings were added for fun, not use.] The beauty of Senet and the work that has been done by many academics is that there are stories within the stories. Especially with the recent work done, in the last decade, there are many more examples of what normal people do, along with influences between nations, spanning thousands of miles, and for people everywhere, every gender, every class, every age. It's amazing how long these stories can last, and just how important the lessons are that we can learn. Rules may change in our world, but underlying themes stay the same; competition is real, but be generous whether you win or lose, expect the unexpected and accept the luck of the toss, think strategically, and keep moving forward.

In looking at the game of Senet from a modern viewpoint, it becomes apparent that the ancient Egyptians held values such as strategy, patience, and persistence in high regard, which are still relevant today. Senet serves as a symbolic representation of life's journey, with its triumphs and setbacks mirroring our own experiences. By reflecting on the strategies employed in senet, we can draw parallels to our decision-making processes. Embracing the timeless lessons of Senet and the multitude of games like it can inspire us to approach challenges with a thoughtful mindset and adaptability, fostering personal growth and resilience in the face of adversity. Just as players navigated the uncertainties of the game, we too can navigate the uncertainties of life with grace and determination, drawing strength from the enduring wisdom encapsulated in this ancient pastime.

Further Reading:

Bell, R.C. (1979) [1960]. Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations. Volume I (Revised ed.). London, UK: Oxford University Press (1960); Dover Publications Inc (1979). pp. 26–28. ISBN 978-0-671-06030-5.

Crist, W., de Voogt, A., & Dunn‐Vaturi, A. E. (2016). Facilitating interaction: Board games as social lubricants in the Ancient Near East. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 35(2), 179-196.

Decker, W. (1992). Sports and games of ancient Egypt. Yale University Press.

Falkener, Edward (1961) [1892]. "§V. The Game of Senat". Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them. Dover Publications Inc. pp. 63–82. ISBN 978-0-486-20739-1.

Finkel, I. L. (2007). Ancient board games in perspective: papers from the 1990 British Museum colloquium with additional contributions. British Museum Press.

Grunfeld, Frederic V. (1975). "Senat". Games of the World. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-0-03-015261-0.

Hornung, E. 1968. Altdgyptische Hollenvorstellungen (Abhandlungen der Sachsischen Akademi e der Wissenschaften 59.3).

Lesko, L. H. The Ancient Egyptian Book of Two Ways. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London, 1972.

Masukawa, K. (2016). The Origins of Board Games and Ancient Game Boards. In Simulation and Gaming in the Network Society (pp. 3-11). Springer, Singapore.

Nogueira, J., Rodrigues, F., & Trabucho, L. (2020). Some Probability Calculations Concerning the Egyptian Game Senet. The College Mathematics Journal, 51(4), 271-283.

Romano, I. B., Tait, W. J., Bisulca, C., Creasman, P. P., Hodgins, G., & Wazny, T. (2018). An Ancient Egyptian Senet Board in the Arizona State Museum. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, 145(1), 71-85.

Sebbane, M. (1990). EB and MB1 Board Games in Canaan and the Origin of the Egyptian Senet Game. Eretz-Israel, 21, 233-238.

Tyldesley, J. A., & Risborough, P. (2010). Egyptian games and sports. Shire Publ..

Citations:

Abbadi, M. (2017). Casanova 2: A domain specific language for general game development. [s.n.].

Aleff, H. P. (2002). The Board Game on the Phaistos Disk: Its Siblings Senet and Snake Game, and Its Surviving Sequel the Royal Game of the Goose. (n.p.): Recovered Science Press.

Assmann, J. (1989). Death and initiation in the funerary religion of Ancient Egypt.

Bell, R.C. (1983). "Senat". The Boardgame Book. Exeter Books. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-671-06030-5.

Bell, R. C. (1983). "Snakes and Ladders". The Boardgame Book. Exeter Books. pp. 134–35. ISBN0-671-06030-9.

Browne, C. (2018, August). Modern techniques for ancient games. In 2018 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence and Games (CIG) (pp. 1-8). IEEE.

Clagett, Marshall (1995) Ancient Egyptian Science: A Source Book, Vol. II: Calendars, Clocks, and Astronomy, Memoirs of the APS, No. 214, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

Collon, Dominique (1 July 2011). "Assyrian guardian figure". BBC History. BBC. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

Crist, W. (2019). Passing from the Middle to the New Kingdom: A Senet Board in the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 105(1), 107-113.

Crist, Walter; et al. (2016). Ancient Egyptians at Play: Board Games across Borders. Bloomsbury. ISBN978-1-4742-2117-7.

Green, William (19 June 2008). "Big Game Hunter". Time. London. ISSN0040-781X.

Jasraj, A. (2017). Snakes and ladders. Lifted Brow, The, (34), 68.

Kendall, T. (1978). Passing Through the Netherworld: The Meaning and Play of Senet an Ancient Egyptian Funerary Game. Kirk Game Company.

Kile, J., 2021. How to Play the Ancient Egyptian Board Game of Mehen – All About Fun and Games. [online] Allaboutfunandgames.com. Available at: <https://allaboutfunandgames.com/how-to-play-the-ancient-egyptian-board-game-of-mehen> [Accessed 29 January 2021].

Krauss, Rolf; et al., eds. (2006), Ancient Egyptian Chronology, Handbook of Oriental Studies, Sect. 1, Vol. 83, Leiden: Brill.

Luft, Ulrich (2006), "Absolute Chronology in Egypt in the First Quarter of the Second Millennium BC", Egypt and the Levant, Vol. XVI, Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, pp. 309–316.

Mehta, G. (2010). Snakes and Ladders. United Kingdom: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Montanari, F. (1995), Vocabolario della Lingua Greca. (in Italian)

Nogueira, J. E. A. D., Rodrigues, F., & Trabucho, L. (2019). On the equilibrium of the Egyptian game Senet. In Recreational Mathematics Colloquium VI-G4G Europe: Book of Abstracts (pp. 195-212). Ludus.

Piccione, P. A. (1980). In search of the meaning of Senet. New York: Archaeological Institute of America.

Piccione, P. A. (1990). The historical development of the game of Senet and its significance for Egyptian religion.

Piccione, P. (1990). Mehen, Mysteries, and Resurrection from the Coiled Serpent. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 27, 43-52.

Robinson, P. (2015). Social ritual and religion in ancient Egyptian board games.

Rothöhler, B. (1999). Mehen, God of the Board games. Board Games Studies, 2, 12-13.

Sebbane, Michael (2001). "Board Games from Canaan in the Early and Intermediate Bronze Ages and the Origin of the Egyptian Senet Game". Tel Aviv. 28 (2): 213–230.

Spencer, D. (2019). Drifting Out to Infinity. Ploughshares, 45(3), 86-115.

Taylor, J. H. (2001). Death and the afterlife in ancient Egypt. University of Chicago Press.

Tetley, M. Christine (2014), The Reconstructed Chronology of the Egyptian Kings, Vol. I, archived from the original on 2017-02-11, retrieved 2017-02-09.

Topsfield, A. (1985). The Indian Game of Snakes and Ladders. Artibus Asiae,46(3), 203-226.

Vermeule, Emily. (1979). Aspects of death in early Greek art and poetry (Berkeley and Los Angeles) -.1983. 'Myth and tradition from Mycenae to Homer,' in Warren Moon (ed.) Ancient Greek art and iconography (Madison): 99-121

Whittaker, H. (2004). Board games and funerary symbolism in Greek and Roman contexts.

Wijoyono, V. V., Negara, I. N. S., & Aryanto, H. (2015). Perancangan Iklan Layanan Masyarakat Penggunaan Gadget Bijaksana Pada Anak Usia 3-5 Tahun Di Surabaya. Jurnal DKV Adiwarna, 1(6), 11.

Winlock, Herbert Eustis (1940), "The Origin of the Ancient Egyptian Calendar", Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, No. 83, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 447–464.