The Eyes on the Waves

In the early days of maritime travel large creatures sailed over the ocean waves, their unblinking eyes ever vigilant to dangers just beyond the horizon.

“At the bows . . . was the ship’s figurehead,

either a ramping red lion or a plain white bust,

or a shield, or some allegorical figure suggested by

the name of the ship . . . [the sailors] took

great pride in keeping it in good repair.”

~ JOHN MASEFIELD, “SEA LIFE IN NELSON’S TIME”

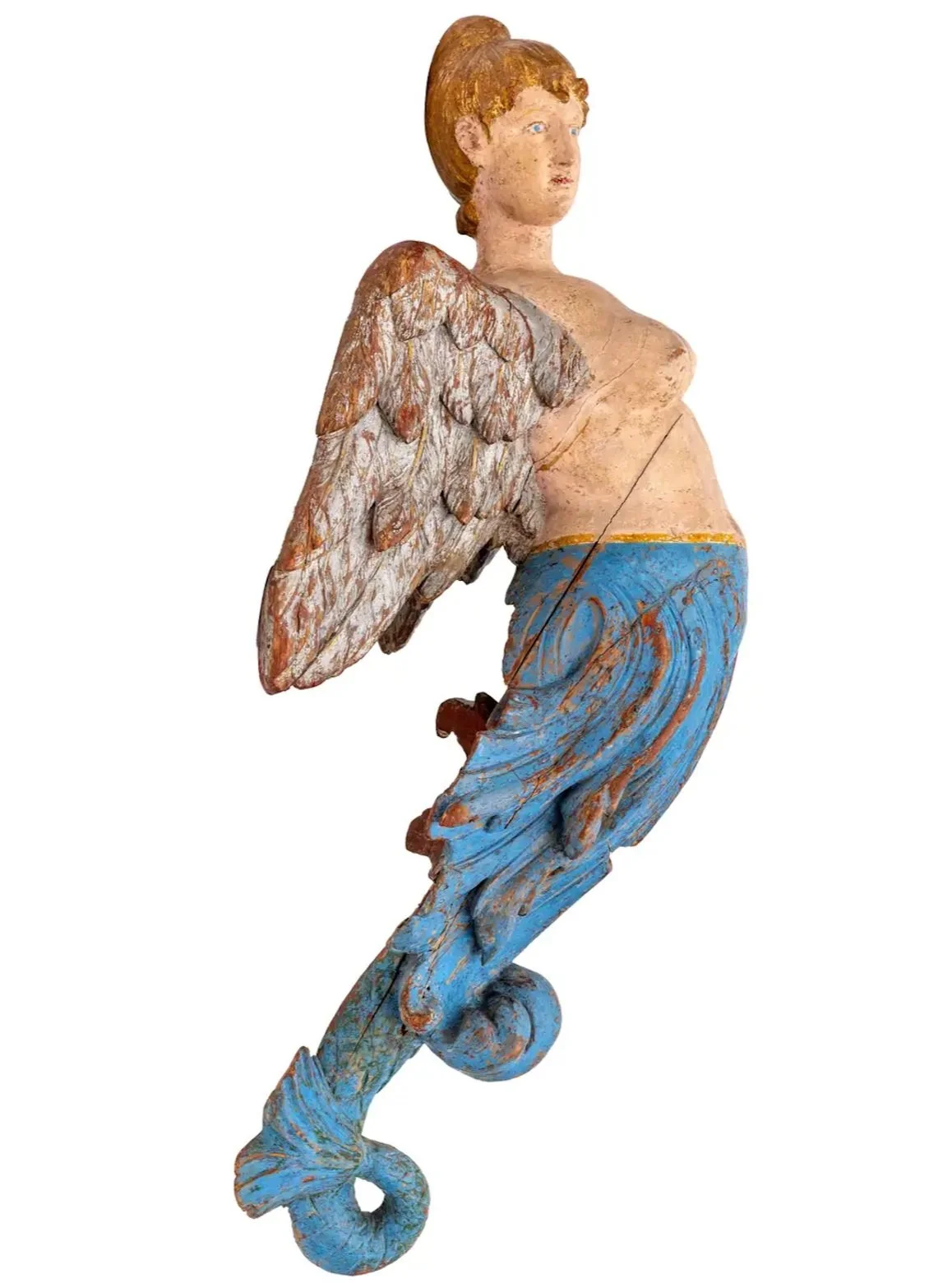

Most of us are well aware of the intriguing existence of figureheads, which are essentially the large, ornamental carvings, vivid paintings, and even real human heads that were originally placed on the bows of ships before being ultimately substituted for more symbolic representations (Kemp 1976). Common examples of these figureheads include enchanting mermaids or other curvaceous women, powerful-looking men, ethereal angels, majestic horses, fearsome dragons, and the list goes on and on (Figure 1-5). These striking figures have historically been said to embody the very spirit of the ship, provide a sense of protection to those aboard, and assist with the various specific goals depending on the form the figurehead would take. Since their fascinating inception in ancient times up to the present day, each unique figurehead has held and continues to hold deep symbolism and meaning, but it is important to note that not all of them have been full, intricate carvings. Some of the earliest sea-traveling peoples, including the Egyptians, Indians, Phoenicians, Greeks, early Romans, and Chinese, built their vessels and adorned them with large, painted eyes on the bow (front) of the ship to serve a myriad of purposes (Encyclopædia Britannica 1999).

From the information gathered, it appears that the animal sacrifices, whether they were tied to the beakhead or the mast, or perhaps set up on a pike, would have occurred first in a sequence of rituals (Jeans, 2007; 308). These specific sacrifices were supposedly two-fold in their overall purpose and significance (Jeans, 2007; 308). Firstly, sacrifices to the Gods were a common occurrence in the ancient world, as people firmly believed that maintaining a good relationship with deities was essential. No one wanted to upset or anger the powerful beings that controlled their fate and fortunes. One only needs to read the Odyssey (the one with the happy ending), or explore Greek myths in general, to see how dire the consequences could be for those who failed to appease the gods. Secondly, the figurehead would be presented as a powerful manifestation of the spirit of the vessel while also keeping a vigilant watch to ensure safe passage through treacherous waters (Figure 6).

Figure 10. Odysseus and the Sirens, Ulixes mosaic at the Bardo National Museum in Tunis, Tunisia, 2nd century AD (wikicommons).

It was common for general locations, such as cities or countries, to mark themselves with their own distinct figures (Figure 7), which, in many ways, remind me of the various flags that represent different countries today. Even as early as 1000 BCE, it was traditional for ships to further specify their identity by painting or carving unique symbols onto the stern of the vessel. The practice of adorning ships with figureheads, drawn from a wealth of cultural symbolism, reveals the profound relationship between ancient civilizations and their environments. Figureheads served not only as ornamental aspects of vessels but also as embodiments of the beliefs and aspirations of those who sailed them.

Figure 11. Wall of ship badges in the Greenwich Maritime Museum, London (Whitehouse 2015).

The Most Ancient

In ancient Egypt, the placement of holy birds at the prow of ships signified a direct connection to the divine, perhaps intended to invoke protection and guidance during maritime journeys (Figure 12). This concept of using the natural world's symbols continued through cultures such as the Phoenicians, who turned to the majestic horse to represent both vision and swiftness—attributes necessary for success in seafaring trade.

Figure 12. A ship with oars bears the fierce lioness that appears as a figurehead on two Ancient Egyptian ships circa. 1200 BC depiction of the victory over the invading Sea Peoples in a battle at the Nile River delta. Unknown artist in the pay of Ramesses III (Gray 1974).

The Greeks, with their boar's head figureheads, emphasized a combination of qualities: acute perception, ferocious reaction, and the readiness to confront threats. Similarly, the Romans, with the centurion's representation, projected an assertive maritime identity, asserting their dominance on the waters through their prime fighting quality", albeit not through physical sacrifices (I hope). Instead, these carvings served as totems of courage and skill.

Figure 13. The figurehead of a warrior on the HMS Surprise is a 1970 replica of the 18th-century Royal Navy frigate Rose.

Transitioning into the Middle Ages, William the Conqueror’s ship, illustrated in the Bayeux Tapestry (Figure 14), showcases the lion on the top of her stem, symbolizing strength and majesty, setting a tone of leadership and power for those who would follow in his wake. By the 13th century, the evolving preference was for the swan as one of the favorite figureheads. The hope was possibly, that the ship would then possess the same mobility and stability as the bird, with its graceful movement across the water, and reflecting a deep desire for both beauty and the seamless navigation that sailors yearned for.

Figure 14. A portion of the Bayeux Tapestry, showing the ships led by William of Normandy in 1066 CE.

Danish ships embraced figures like the dolphin and bull, while the serpent became a favoured motif in Northern Europe with the Vikings, embodying elements of mystery and protection (Figure 15)(Kemp 1976).

Figure 15. Figurehead monster from a Danish Warship sunk in 1495 lifted from the Baltic Sea (Reddit 2020).

Common Viking Figureheads and Their Symbolism

Viking longships are renowned not only for their impressive engineering but also for their intricately crafted figureheads. These carved pieces, often depicting animals or mythical beings, served both an aesthetic and symbolic purpose, reflecting the beliefs and values of the Norse culture. The Griffin ship's figurehead, depicting a beast swallowing a man, exemplifies how these carvings could represent the vessel's spirit as well as its name or owner (Eriksson, 2020).

Dragons and Serpents

The most iconic Viking figurehead is the dragon. Often depicted with fierce-looking jaws and scales, these figureheads were believed to fend off evil spirits during sea voyages. The dragon symbolizes strength and resilience, embodying the warrior spirit of the Viking people. It was thought that dragons could breathe fire, thus offering protection and courage to those who ventured into the unknown.

Another common design features serpents, such as the Jörmungandr aka Midgard Serpent from Norse mythology. These figureheads represented danger and the formidable forces of nature. The serpent's presence signified that a ship was not just a vessel of transportation but a carrier of warriors ready to confront challenges. When displayed as a spiral shape, these figures often suggested the cyclical nature of life and death, aligning with the Vikings' deep respect for the natural world. The Birka dragonhead dress pins of the unique "Birka style" [on the island of Björkö (lit. "Birch Island") in present-day Sweden, was an important Viking Age trading center which handled goods from Scandinavia (Price et al. 2018 )] to Viking Age artifacts show that dragon and serpent motifs displaying Jörmungandr were particularly prominent (Figure 19) (Kalmring & Holmquist, 2018). Anthropomorphic images from the Vendel and Viking Ages were powerful communication media, often blurring the lines between representation and reality in these largely oral societies (Helmbrecht, 2011). These images appeared on various objects, including gold foil figures, clothing components, and coins, with the motifs and carriers evolving. The imagery conveyed messages of wealth and complexity, functioning as active social strategy devices while providing communication lines with "other worlds" through their perceived power and artistic production (Helmbrecht, 2011).

Figure 19. Replica of a Viking Serpent Brooch (https://www.northanvikingsilver.com/products/viking-serpent-brooch).

Eagles

Symbolizing nobility and power, eagles were also prevalent among Viking figureheads. These majestic birds were associated with Odin, the chief god in Norse mythology, who was depicted with two eagles, though more often depicted with his ravens Huginn (“thought” in Old Norse) and Munin (“will” in Old Norse). The eagle figurehead represented divine guidance and protection. It was believed that an eagle's keen eyesight could foresee danger at sea and ensure the crew's safety.

Bears

Another popular motif held that bears symbolized ferocity and bravery in battle. Viking warriors often revered bears, not just for their strength but also for their connection to the earth and nature. A bear figurehead served as a rallying point for the crew, embodying the raw power they aspired to showcase.

Human-shaped

Human figureheads were often carved to resemble warriors or gods meant to inspire and embolden the crew. These figures were affiliated with the idea of valiant ancestors watching over the ship, protecting it during dangerous voyages. Additionally, they signify the importance of honour, legacy, and the connection between past and present warriors.

Horses

Like the Phoenicians Vikings also carved figureheads in the shape of horses, symbolizing travel, mobility, speed, and agility, significant themes in the Vikings' seafaring adventures and their ability to explore new lands, much like horses carried them across the rugged terrains of Scandinavia.

In the more ancient of those listed above, the Egyptians, Phoenicians, and Greeks, the latter two built Triremes, which became the most common warship style. While they fell out of fashion in the Peloponnesian War with the rise of the quadriremes and quinqueremes after the Persian Wars and the creation of the Athenian maritime empire (Morrison, 1968), they seem to be synonymous with the painted eyes. The Athenians would change up the use by carving the prow as a battering ram. Therefore, instead of being only symbolic the fear of the 'creature' would be actionable.

Fleet of triremes made up of photographs of the modern full-sized replica Olympias. An EDSITEment-reconstructed Greek fleet of galleys based on sources from the Perseus Project.

The Triremes, with their elegant and powerful design, represent a fascinating intersection of art and warfare in ancient maritime cultures. The use of actual triremes by Egyptians is disputed by modern historians. The source is attributed to Herodotus, who mentioned that the Egyptian pharaoh Necho II (610–595 BCE) built triremes on the Nile, for service in the Mediterranean, and in the Red Sea. However "triērēs" was by the 5th century used in the generic sense of "warship" (Mispelkamp et. al 1996).

Phoenicians and Greeks not only utilized these warships but infused them with symbolism, particularly through the painted eyes. These eyes, often depicted on the bow of the ship, served as a formidable emblem, designed to strike fear into the hearts of adversaries. It was believed that they offered protection against evil spirits and guided the ship on its journey, embodying the belief that the vessel was alive and possessed a spirit of its own.

As the dynamics of naval warfare evolved, so too did the design and function of these ships. The transition from the sleek Triremes to the more robust quadriremes and quinqueremes reflected the changing tactics and strategies prevalent during the Peloponnesian War. The Athenian innovation in modifying the prow into a battering ram not only transformed the ship's functionality but also deepened the connection between art and action. The 'creature' on the prow, with its gazing eyes, became a harbinger of psychological warfare; it wasn't just a decorative element but a radical assertion of power and dominance on the battlefield.

This interplay of artistry and warfare reveals a lot about the cultural values and beliefs of these ancient civilizations. They understood that symbols carried weight, and the representation of the painted eyes and the fearsome creature embodied both artistic expression and strategic ingenuity. By examining these maritime marvels, we uncover not just the evolution of naval technology but also the profound ways in which art has the capacity to influence, protect, and instil dread—legacy messages that resonate even today.

What looks to be the case (pun completely intended) is that no matter what style of the ship, the eyes were of use, merchant ships for protection, warships for fear, both to honour the Gods. Phoenician ships included eyes that were intended to help the ship “see” and to frighten enemies, as well as horses’ heads to honor their god of the sea, Yamm. Egyptian ships, the earliest of which were made of reeds dating around 6000 BCE later changed to the styles with sails which used timber harvested after Hatshepsut establishing trade routes with Lebanon dating back to approx. 1470 BCE (or 3450 BP). The funeral barges and the later trading vessels had a falcon or falcon eyes, the symbol of Horus and thus the pharaoh who was Horus' living embodiment. Under Ramesses III (reigned from 1187-1153 BCE) continued the expansion of Egyptian trade routes by having vessels sail across the Indian Ocean. All of these trade routes would grow over time and eventually become the long Maritime Silk Route, with stops ranging from Rome to China and even Southern Japan.

This map indicates trading routes used around the 1st century CE centred on the Silk Road. The routes remain largely valid for the period 500 BCE to 500 CE (by Whole World Land And Oceans published on 15 March 2018).

Trade ships in India and the Junk ships in China (2800 BCE) are also reported to have eyes painted on the bow area. The Chinese junk ships were used earliest for exploration, trade, and warfare around Southeastern Asia and they also likely traded with India by the 7th century CE based on Muslim writings in the Euphrates valley (Waldman, 2004). The small jumps in between countries, which eventually created a large leap may have been fully connected by between 1500 and 1000 BCE*. Chinese junks played a crucial role in maritime commerce for over 2000 years, providing cheap transport in areas on rivers and coastal areas that lacked modern infrastructure or where other modes of transport were inadequate or prohibitively expensive (Wiens, 1955). These vessels varied greatly in size and design, from small rivercraft to large ocean-going ships capable of long-distance voyages to India (Wake, 1997). These vessels served as the primary means of maritime trade for Southeast Asian kingdoms until the arrival of Europeans in the 16th and 17th centuries (Manguin, 1980).

A 19th century CE oil painting of a traditional Chinese junk ship, used for ocean-going trade voyages since medieval times. (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London).

The ocean-going junks of southern China, particularly those from Quanzhou in Fujian province, were renowned for their impressive size during the 12th to 15th centuries. Contemporary Chinese, Arab, and European sources described these ships as being "very big" and "like houses" with sails resembling "great clouds in the sky" (Wake, 1997). Despite the introduction of steam and motor shipping, junks maintained their significance in China's transport system, especially during periods of modern vessel shortages (Wiens, 1955).

Junks have eyes to see where they are going (Old Shanghai 1945).

Junks and the eyes painted on them were highly specialized, with fishing vessels featuring low-set eyeballs to spot fish, while trading junks had forward-facing eyes to detect unseen dangers (Howell, 1948). Traditionally known as “eye of the wind” or “eye of the sea,” these painted eyes are believed to ward off evil spirits and ensure safe passage through treacherous waters. This practice reflects a deep-rooted connection between maritime culture and spirituality in ancient Chinese beliefs. By giving the boat a visual “soul,” sailors invoke divine intervention, seeking favour from protective deities while navigating the vastness of the sea. This symbolism represents safety and also highlights the junks’ role as continuous ‘living’ sentinels of maritime tradition, carrying stories and legends across generations.

Further Into the South and Pacific

Figure . The ceremonial barge used during the annual Phaung Daw U Pagoda festival in Myanmar uses a figurehead at the right of a karaweik, a mythical bird (Gerd Eichmann).

The seafaring Māori of Aotearoa (New Zealand). The figurehead on a Māori waka, or canoe, is called a pakoko or tete. The figurehead is often carved with a defiant face, a protruding tongue, and outstretched arms. The figurehead may also have a feather wig or be adorned with long wands and bunches of feathers. Some examples of Māori waka figureheads include a figurehead from a war canoe that depicts the god of war, Tūmatauenga, warning his brother, the god of the sea, that humans are crossing his domain. A carved male head with traditional full facial tattoos, or moko, from the prow of a waka built in response to the 1822 slaughter at Tōtara pā. Fishing canoes had a tiki head with a thick tongue and curved and spiral patterns around the mouth that likely represented moko. The eyes were inlaid with iridescent shells. The waka is a symbol of Māori history as navigators, voyagers, and innovators. It also represents commitment, kotahitanga, and teamwork.

Indigenous American canoe figureheads serve as significant cultural artifacts, reflecting the rich symbolism inherent in the artistic expressions of various tribes. Traditionally, these figureheads were carved from hardwood, often representing animals or ancestral spirits with deep spiritual significance. Animal motifs, such as eagles or bears, often symbolize qualities like strength, vision, and courage, which directly relate to the characteristics admired within the tribes. For instance, the Tlingit canoe figureheads often depict the raven, a crucial figure in their mythology, embodying the transformative qualities of creation and change. The intricate designs also encapsulate tribal identity, connecting contemporary artisans to their ancestors while conveying communal narratives and history. Moreover, these figureheads were believed to protect the vessel and its occupants during travel, fortifying the canoe with spiritual power as it traversed the waters. Thus, the symbolism of canoe figureheads embodies a complex interplay of mythology, identity, and spirituality, reflecting the vast cultural tapestries of Indigenous American societies.

American Museum of Natural History, New York City, 2015 Source: Canoe figurehead Author Thomas Quine

Figure. “Bill Reid’s renowned Loo Taas (Wave Eater)” Photo Courtesy of CanadiadRoadStories.ca

While the use of figureheads was common in many maritime cultures, but in Japan, they seem to only become significant on warships during the rise of the samurai and merchant classes primarily during the Edo period (1603-1868) after connection to the west and prior to the full closing of borders. These decorative carvings such as the eastern dragon were placed on the prow of vessels and served not only as ornamental pieces but also carried symbolic meanings. The intricacies of their designs often conveyed messages of protection and good fortune. Although figureheads are less common in Japanese maritime tradition, their historical significance can still be appreciated in museums among traditional wooden vessels like the figurehead from the old RMS Empress of Japan, in Vancouver (Figure).

We know that with trade comes cultural change. Did the stories exchanged make a difference in the arts and ship figurehead ideas?

A Change in Venue

When planes started being used in battle they would paint eyes or faces on planes as well, especially popular in the earlier days of flight, and going through WW2 (Figures ) [first two pictures are from WWI examples, and the last 5 are examples from WW2]. The paintings on airplanes were often referred to as "nose art". Traditionally seen on military planes, nose art became a way for pilots to express their individuality, camaraderie, and superstitions. These illustrations can range from playful pin-up girls to fierce creatures or even whimsical characters. However, they not only reflect a sense of connection between the creativity and spirit of the members of the crew but also embody the mission and history of the aircraft itself. Today, while some commercial airlines may feature more sanitized designs, the essence of these artistic expressions continues to resonate, reminding us of the rich stories and cultural significance woven into the fabric of aviation history.

While it isn’t the same, people still put decals on and “pimp their rides” to gain favour from their peers and look “extra”.

The evolution of figureheads across centuries and cultures illustrates the complex interplay of societal values, artistic expression, and spiritual beliefs. More than mere decorative elements; they were imbued with profound meanings and were essential to the understanding of each culture in which they featured. Each figurehead reflected the values, beliefs, and aspirations of the people and served as a formidable symbol of protection and identity as they embarked on their journeys across treacherous waters. The legacy of these magnificent carvings continues to resonate today, reminding us of the intricate relationship between art, mythology, and the human spirit. Initially, figureheads served as symbols of protection and guidance, often adorned on the prows of ships to invoke favour from deities during perilous voyages. Their designs varied significantly based on cultural contexts; for instance, some cultures favoured mythological figures that invoked strength and protection, while other cultures were described to have used animal representations that held deep spiritual significance.

As societies progressed, the role of figureheads transcended mere symbolism, embodying ideals of leadership, identity, and community values. In ancient Rome, for instance, figureheads were likened to the image of emperors, reinforcing authority through both political and divine legitimacy. In contrast, both Eastern and Western cultures used animal motifs that symbolized various virtues, reflecting a collective harmony with nature and an emphasis on spiritual balance.

The materials used for figureheads also evolved, influenced by technological advancements and resource availability. Wood was predominant in early representations of figurehead sculptures, but they began to take on diverse forms and expressions with the introduction of metals and plastics. This shift showcased various cultures' artistic skills and reflected changing attitudes towards material wealth and craftsmanship.

Cultural exchanges further enriched the evolution of figureheads. Trade routes facilitated the sharing of ideas and artistic styles, leading to hybrid forms that merged distinct cultural elements. This diffusion of practices can be seen in the ornamental figureheads of colonial ships, where European designs fused with indigenous symbolism to create unique representations.

In conclusion, each figurehead chosen carried with it a story, a myth, or a legend—a connection to nature and a reminder of the human experience intertwined with the unpredictability of the sea. Such emblematic representations extend beyond their artistic merit; they embody the very spirit of exploration in both ancient and modern maritime cultures, bridging the gap between the past and present. The transformation of figureheads over the centuries highlights a rich tapestry of cross-cultural influences, shifting societal values, and artistic innovation. Each figurehead serves as a mirror reflecting the beliefs, aspirations, and identities of the cultures that created them, underscoring the profound significance of artistry in understanding human history and connection across the globe.

If we don't do it anymore, what could we lose? Are we still superstitious? Maybe it's just fun...maybe it’s important to keep these connections alive.

Citations:

Costa, G. Figureheads: carvings on ships from ancient times to twentieth century Lymington: Nautical, 1981

Encyclopedia Britannica. (1999). Figurehead | sculpture. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/art/figurehead.

Eriksson, N. (2020). Figureheads and Symbolism Between the Medieval and the Modern: The ship Griffin or Gribshunden, one of the last Sea Serpents? The Mariner's Mirror, 106, 262 - 276.

Gray, Dorothea (1974) "chapter G" in (in German) Seewesen, Archaeologia Homerica, I, Göttingen, pp. 166−167

Helmbrecht, M. (2011). Wirkmächtige Kommunikationsmedien: Menschenbilder der Vendel-und Wikingerzeit und ihre Kontexte (Vol. 30). Lund University.

Howell, E. B. (1948). China. Edited by Harley Farnsworth MacNair. 8¾× 5¾, pp. xxix+ 573. The United Nations Series. University of California Press. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 80(1-2), 80-81.

Jeans, Peter D. Seafaring lore and legend. McGraw Hill Professional, 2007.

Joshua J. Mark. “Phoenicia,” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified September 02, 2009. http://www.ancient.eu/phoenicia/.

Kalmring, S., & Holmquist, L. (2018). ‘The gleaming mane of the serpent’: the Birka dragonhead from Black Earth Harbour. Antiquity, 92, 742 - 757.

Mispelkamp, Peter K.; Morrison, John; Gardiner, Robert; and Greenhill, Basil (1996) "The Age of the Galley: Mediterranean Oared Vessels since Pre-classical Times," Naval War College Review: Vol. 49: No. 2, Article 33.

Morrison, John S., David Morrison, and R. T. Williams. Greek Oared Ships 900-322 BC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968.

Price, T. D., Arcini, C., Gustin, I., Drenzel, L., & Kalmring, S. (2018). Isotopes and human burials at Viking Age Birka and the Mälaren region, east central Sweden. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 49, 19-38.

Wake, C. (1997). The great ocean-going ships of southern China in the age of Chinese maritime voyaging to India, twelfth to fifteenth centuries. International Journal of Maritime History, 9(2), 51-81.

Waldman, Carl, and Alan Wexler. Encyclopedia of Exploration, Vol. 1-2. New York: Facts On File, 2004.

Weaver, Stewart A. Exploration: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Wiens, H. J. (1955). Riverine and coastal junks in China's commerce. Economic geography, 31(3), 248-264.

Further Readings:

(1938). Model Chinese Junks. Nature, 142, 789-789.

Tiboni, F. (2006). Animal‐Shaped Figureheads and the Evolution of a ‘Keel‐Post‐Stem’Structure in Nuragic Bronze Models and Boats between the 9th and 7th Centuries BC. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 35(1), 141-144.

http://cultureandcommunication.org/deadmedia/index.php/Nautical_Figureheads

https://historydaily.org/the-history-of-ship-figureheads

https://www.marineinsight.com/maritime-history/what-is-ships-figurehead/

![Figure 17. "...[T]he dragon figurehead, if it was available, was removable. When the ship entered its home bay, the dragon's head was removed." Author: Elena Stanislavova 2022](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6598c864ea0f89700c0e4e59/1731272549120-IYI09A6OAOTLO3G0H4UV/1727054e0588a9726c01b491f6c05fa5.jpg)