The Resurrection of Pakal

In 2013, I traveled to Mexico for the first time as part of my university archaeology course, focusing on the Maya in Mesoamerica. Our professor, Dr Geoffery Braswell, led us to dozens of sites in southeastern Mexico and northern Guatemala over a two-and-a-half-week period. Every night a few of us students went out to dinner with our professor and listened to his stories while drinking cervezas and sipping good tequila. Years later, I was taken back to those enjoyable evenings once I found podcasts. So as one of my original inspirations, I’m dedicating this episode of Artaeology to Dr. Geoffery Braswell. Here is “The Resurrection of Pakal”.

—

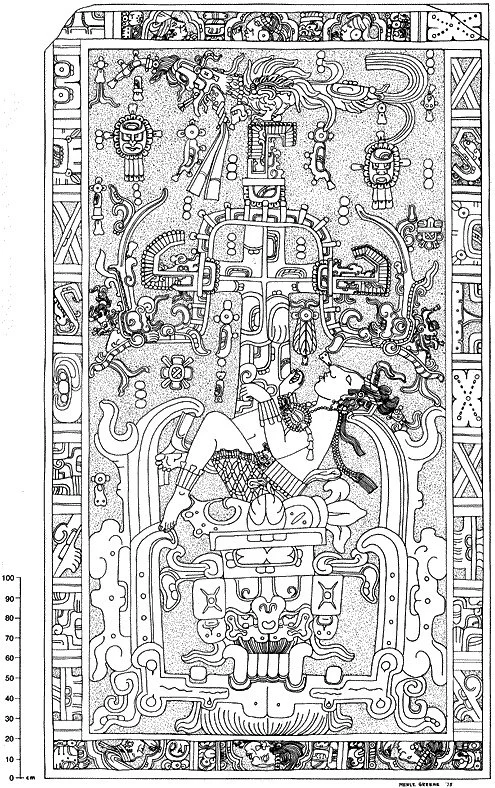

Perched up against the wall inside the lobby of Hotel Xibalba in Chiapas, Mexico is a replica of the coffin lid of K’inich Janaab’ Pakal I (Figure 1). His full name translates to "Radiant Corn-Flower (?) Shield” and is rendered in Classic Mayan as KʼINICH-JANA꞉B-PAKAL-la, KʼINICH-JANA꞉B-pa-ka-la, or KʼINICH-ja-na-bi-pa-ka-la who is also known as the ahau/ajaw (king) of Palenque in the Late Classic Period (Figure 2)(Skidmore 2010: 71-73, Martin & Grube 2008: 162). Before his name was securely deciphered from Maya inscriptions, Pakal had been known by various nicknames and approximations, including Sun Shield and 8 Ahau. He is additionally thought by some archaeologists to also be the king referred to as “Casper” because the name glyphs are too broken to read, so whoever it is is referred to as a friendly ghost (Skidmore 2010). For simplicity’s sake, he will be identified as Pakal.

Born in March 603 CE (9.8.9.13.0 on the Mesoamerican Long Count Calendar*), Pakal took over the throne when old enough, at age 12 on the 27th of July 615 (9.9.2.4.8), from his mother, Lady Sak K’uk’, [which means White Quetzal] (Tiesler & Cucina 2004: 40). She was the ahau before him instead of his father Kʼan Moʼ Hix because he was only a nobleman of the city-state of Palenque and she was the direct heir of her father Janahb Pakal. Lady Sak K’uk’ has her own extensive story as a highly influential ruler of great importance in Mayan history and is depicted on the coffin lid of her son (Figure 3). (Skidmore 2010: 71, Martin & Grube 2008: 162-168).

Figure 2. (left) K’inich Janaab’ Pakal name name glyphs.

Figure 3. (right) Portrait of Lady Sak K’uk’ on Lintel 615 at Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico.

Pakal was 80 years old when he died on 9.12.11.5.18 (August 683) and reigned for 68 years and 33 days (Tiesler & Cucina 2004: 40). He had a long reign he accomplished a great deal and became known as Pacal (Pakal) the Great, which I’m only going to summarize a few highlights here. During the classic period, from c. 200-910 CE the number of Mayan cities quickly grew, there were as many as 60 in the eighth century and they would fight regularly, especially between the city-states of Tikal and Calakmul (Figure 4)(Schele et al. 1999: 18).

Palenque was in the midst of a particularly turbulent time in its history. Four years before Pakal was born, Palenque had been sacked by Calakmul, which lies only 239 km or about 148.5 miles away. During Pakal's early childhood, another catastrophic attack was led by Calakmul’s ahau Scroll Serpent in 611 (Figure –) (Carrasco 2012: 132). The following year, when Pakal was 8 or 9 years old, the deaths of both the ruling Palenque ahau Ajen Yohl Mat and his heir Janahb Pakal (Pakal's maternal grandfather and namesake) triggered a crisis of succession, and about 4 years later Pakal became ahau of the kingdom B’aakal within the city-state Palenque (Grube 2006:146, Martin & Grube 2008: 162-165).

During his time as ahau, Pakal increased Palenque's influence in the western Maya nations and launched a building program at his capital that resulted in some of the finest Maya art and architecture (Martin & Grube 2008: 162-168) On 9.9.13.0.7 (March 626), he married Ix Tzʼakbu Ajaw, a descendant of the former ruling Toktahn dynasty from Palenque's satellite settlement of Uxteʼkʼuh. During their long marriage, they had at least two sons—Kan Bahlam II (b. 635) and Kʼan Joy Chitam (b. 644)—and probably a third, Tiwol Chan Mat (b. 648) (Tiesler 2006).

Piedras Negras captured a Pakal official (aj kʼuhuun) in 628. Six days later, Nuun Ujol Chaak, ahau of Santa Elena (as it is now called), was apprehended and brought to Palenque, so Santa Elena became a tributary of Palenque. In 659, Pakal apprehended six convicts, one of which, Ahiin Chan Ahk, came from Pipaʼ, also known as Pomona. In 663, Pakal killed a leader from Pipaʼ and captured six Santa Elena people (Skidmore 2010: 71-73).

Moving on to his monumental architecture, Pakal began his first construction project in 647 CE. At the age of 44, he built the temple now known as El Olvidado (The Forgotten) in Spanish due to its remoteness from Lakamhaʼ. The Palenque Palace is one of Pakal's most successful construction projects (Figures 5 - 6). The structure was already in place, but Pakal substantially expanded it by adding memorial rooms to the existing level. He next built Building E, known as "White Skin House", Sak Nuk Naah in Classic Maya because of its white paint rather than the red used elsewhere in the palace. Pakal's monuments and texts include the Oval Palace Tablet, Hieroglyphic Stairway, House C writings, Subterranean Thrones and Tableritos, Olvidado piers, and sarcophagus texts (Figure 7)(Martin & Grube 2008: 162).

Tragedy struck on 9.12.0.6.18 (November 672) when Pakal's 47-year-old wife, Tzʼakbu Ajaw, passed away. Then, eight years later, Pakal also presided over the funeral of Tiwol Chan Mat (his third son)(Tiesler 2006). In the final years of his long life, Pakal created the Temple of the Inscriptions as a burial monument to himself (Figure 8). According to a date documented in the stucco sculpture of the piers, the structure started construction before 678 CE, possibly as early as 675 CE, and was dedicated on July 6, 690, seven years after Pakal's death (Schele and Mathews 1998: 97–99, Carrasco 2012: 129). If the dates of the Temple of the Inscriptions are true, Pakal died five and a half years into the construction process, around halfway through. K'inich Kan Bahlam II, Pakal's son and successor, would spend an additional five years completing the temple's construction and adornment. While there is some evidence of haste in the final carving of the coffin deep within the temple, this evidence cannot be observed in the outside design (Robertson 1983:63, Carrasco 2012: 4). This suggests that Kan Bahlam II had the tomb decoration rapidly done following his father's death before sealing the tomb and then finished the rest of the temple decoration at a much slower and more deliberate pace (Carrasco 2012: 4).

Pakal’s coffin, complete with his remains, is still buried underneath the Temple of Inscriptions (Figure 9). The coffin itself has dimensions of approximately 4.5 meters long, 3.6-4.2 meters high, and 2 meters wide (15ft long, 12-14ft high, and about 7ft wide). For this piece we’ll be focusing on the lid, the story of Pakal being resurrected into Xibalba, the spirit world.

Although we won’t be focusing on the other surfaces or the other monumental groups in this article, it is valuable to know that much of the history that we have is based on the inscriptions on the Temple of Inscriptions and Pakal’s tomb which archaeologists and linguists translated. This just means that the known history could be colored to support Pakal and his family, not to say that it’s wrong. There are name glyphs next to seated kings are carved around the outside (Figures 10 - 13). These are Pakal’s ancestors and previous king which is a method of proving Pakal’s right to rule even after his death. Further, using these depictions we can identify the kings in the Temples of the Cross Group built by Kan Bahlam II in the 690s. This is because he followed the stylistic aspects that he and Pakal developed as they supposedly worked on Pakal’s funerary structures together (Carrasco 2012: 141).

Figures 10-13. Close up shots of the coffins ancestor king carvings on the sides of Pakal’s coffin (reproduction) (Whitehouse 2013).

—

Before getting into what archaeologists, anthropologists, and ethnographers think the symbolism behind the coffin lid means. The notion of aliens needs to be addressed. As an archaeologist who studied the region, if even for a short time, it is clear that Pakal is NOT being carried up into outer space and ideas like this are hurting the discourse of taking mythological symbolism seriously as allegory. These myths were intrinsic to whoever could see the peice and most assuredly to Pakal and his family, whether it was to make Pakal feel better as he reached the end of his life or more likely keep the family in power with a deified ancestor.

—

Working our way from the outside in, the coffin lid’s carving has a framing like many other works of art and this one is filled with symbols and glyphs (Figure 14). The top and bottom are mirror images of each other with three faces in profile peering through quatrefoils. These are portals between our world and the underworld (Xibalba**), each are individually called a Hol and look like four-leaf clovers. Next to each clover are glyphs naming the faces as specific Sabal, secondary lords who are looking from our world to the other. And since the human desire to be remembered never changes archaeologists think that there are also signatures of the main architect, artist, and scribe who worked on the pyramid and on the burial chamber, which included the coffin.

In the middle of the lengths of the border frame is the sun in the east (on the right side) where it rises, and the moon in the west (left) where the sun sets, which is often the direction to the spirit realm or underworld. The moon is depicted as a rabbit coming out of a cave, the doorway to Xibalba, because the Maya traditionally told the story of the rabbit in the moon, similar to various Asian cultures, and symbolically just like European traditions that talk about seeing the man in the moon. Around the rest of the frame and in the negative space within the inner composition are common Mayan astrological symbols: shells, stars, and jade bones signifying that the entire scene is being framed by the cosmos (Figure 15).

Looking inward the eye is first drawn to the lower center, where Pakal, who passed at a ripe old age, is shown as a young man sitting in a fetal position as if he were being born from the world tree as it rises from the bony jaws of the earth monster’s mouth. The 4-part monster on which Pakal is resting has the base of the bone jaw with a beard underneath its eyes, ear florets, and a ceramic plate holding up three objects of great significance to the Maya people.

Moving from left to right, the first is a seashell signifying the watery underworld. The second/middle symbol is a rounded version of a stingray spine, in the ancient Maya tradition kings and queens would sacrifice a piece of themselves to the gods. In this case, it would be through bloodletting, for men it involved piercing the foreskin of the penis with the stingray spine and for women, it was through the use of a rope of thrones being flossed through their tongues. In either instance, the blood would be caught on paper strips and then burned so the blood in the smoke would be carried up to the gods. The symbol on the right, the circle with the glyph that looks like the “%” sign, means ‘death’ with a piece of corn/maize growing out sideways from the circle. Altogether this means that Pakal’s human body was an offering of blood from the underworld and he reveals himself to be the maize god.

Pakal is depicted in this way to show how he should be considered a deity, in particular, the Young Maize God or as a combination of the Hero Twins. Pakal is dressed in a skirt, bracelets, and anklets all made from jade beads none of which are typically masculine wear, even for the time. The purpose of this clothing is to represent the feminine aspects, as one incarnation of the hero twin mythos is one male and one female, and the maize god, as the paramount god, must embody characteristics from both traditionally recognized genetically prescribed human sexes. Pakal is also wearing a cracked turtle shell on his bead necklace, harkening back to the creation myth when the world tree first grew from the shell, a nose piercing, and an elongated headdress. The headdress, a common motif in Mesoamerican stelae and a common piece of Mesoamerican kingly-warrior garb is not a sign of godliness in itself but is a sign of sacrifice and god worship. It contains the symbol of K’awill, the smoking axe, representing kingship and the god of same. On the back base of the crown are two strands of beads with what could be short feathers hanging down under what also could be the long feathers of the quetzal bird, which the Maya bred and raised in pens in multiple cities and were highly prized status symbols.

Following Pakal’s eye-line, we look upward towards the cross shape behind him, Wak Kak Chan or Yax Imix Che, the World Tree, the “Green Tree”, or the “First Tree” (Figure – wiki tree) (Dick et al 2007: 3039-3049, Knowlton & Vail 2010: 709-39, Yunus Khan et al. 2015: 367-73). This giant Ceiba tree (Ceiba pentandra), also known as a Kapok or silk-cotton tree, has held up the heavens since the hero twins won the ball game at the beginning of creation. Draped over the branches is a two-headed snake. Each head symbolizes kingship, with K’awill on the left and Sa Bu Nall, the Jester God, on the right. According to Dr Braswell (2013), the tree itself is personified, depicted with two eyes and a nose, while also being covered in heavenly symbols. One of these symbols is Yax, meaning the ‘green of the green’, which symbolizes the spikey and cross-like form of the Ceiba tree. The tree is also growing three serpentine-like heads, one out of each of the branches complete with the fuzzy maize tassels as headdresses as a means of connecting the story of the world tree to the birth and death of maize. This is another way that Pakal is performing deity imitation.

The last major piece of iconography is the otherworldly bird sitting on the top branch. The bird itself Itzam Ye, is a symbol of or the bird-form stand-in for the creation god/creator-sorcerer Itzamná, who is forever watching over our creation (Mark 2012, July 07).

Ultimately, this carving shows the deceased Pakal as an offering resurrected from Xibalba, the underworld. He is presenting himself as the young maize god, who is one of, if not the most important character in the creation myth and the story of maize. As the hero of humanity, he is the gift, bolstered by the world tree behind him and holding him as well as other symbols of the heavens and kingship with the representation and the approval of a premier god of creation. This scene is therefore not only one of death but one of resurrection. Displaying the divine nature of the king as the young maize god and thus the constant cycle that follows the natural world.

This work of art can be seen in dozens of places, hundreds if you include the Internet, including Hotel Xibalba, Palenque’s local site museum, and the National Museum in Mexico City. These are all copies though, and the only place to visit the original is still within the Temple of Inscriptions, deep in the rainforest of Chiapas, Mexico, where the mouth of the cave waits for the rabbit of the moon.

Asides

* The Long Count calendar identifies a date by counting the number of days from a starting date that is generally calculated to be August 11, 3114 BCE in the proleptic Gregorian calendar or September 6 in the Julian calendar (or −3113 in astronomical year numbering). There has been much debate over the precise correlation between the Western calendars and the Long Count calendars. The August 11 date is based on the Goodman-Martinez-Thompson (GMT) correlation.

The Mesoamerican Long Count calendar is a non-repeating base-20 and base-18 calendar used by several pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures, most notably the Maya. For this reason, it is often known as the Maya Long Count calendar. The two most widely used calendars in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica were the 260-day Tzolkʼin and the 365-day Haabʼ. The equivalent Aztec calendars are known in Nahuatl as the Tonalpohualli and Xiuhpohualli, respectively. The combination of a Haabʼ and a Tzolkʼin date identifies a day in a combination which does not occur again for 18,980 days (52 Haabʼ cycles of 365 days equals 73 Tzolkʼin cycles of 260 days, approximately 52 years), a period known as the Calendar Round. (Bricker & Bricker 2011).

** Xilbalba could be found in Classical Chʼoltiʼ, the oldest known member of the Mayan language family. It is the primary language known in pre-Columbian inscriptions from the Maya civilization's classical period. It is also the shared ancestor of the Cholan branch of the Mayan language family. Contemporary descendants of classical Maya include Chʼol and Chʼortiʼ. (Houston 2000: 321-356.)

***Many of the photos are my own work and the majority of the information examining the lid came from my professor Dr. Geoffrey Braswell at UCSD on the archaeological study abroad summer trip to Mexico and Guatemala in 2013.

Citations

Aoyama, K. (2005). Classic Maya Warfare and Weapons: Spear, dart, and arrow points of Aguateca and Copan. Ancient Mesoamerica, 16(2), 291–304.

Braswell, J. (2013, September 12). The Mysterious Maya [Study Abroad Ancient Mesoamerica]. UC San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA.

Bricker, H. M., & Bricker, V. R. (2011). Astronomy in the Maya codices. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

Carrasco, M. D. (2012). The History, Rhetoric, and Poetics of Three Palenque Narratives. Parallel Worlds: Genre, Discourse, and Poetics in Contemporary, Colonial, and Classic Maya Literature, edited by Kerry M. Hull and Michael D. Carrasco, 4th ed. edition, 123-79.

Dick, C. W., Bermingham, E., Lemes, M. R., & Gribel, R. (2007). Extreme long‐distance dispersal of the lowland tropical rainforest tree Ceiba pentandra L.(Malvaceae) in Africa and the Neotropics. Molecular Ecology, 16(14), 3039-3049.

Grube, N. (2006). Ancient Maya Royal Biographies in a Comparative Perspective. Janaab Pakal of Palenque: Reconstructing the Life and Death of a Maya Ruler, 146-166.

Houston, S., Robertson, J., & Stuart, D. (2000). The language of Classic Maya inscriptions. Current Anthropology, 41(3), 321-356.

Knowlton, T. W., & Vail, G. (2010). Hybrid cosmologies in Mesoamerica: A reevaluation of the Yax Cheel Cab, a Maya world tree. Ethnohistory, 57(4), 709-739.

Mark, J. J. (2012, July 07). The Mayan Pantheon: The Many Gods of the Maya. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/415/the-mayan-pantheon-the-many-gods-of-the-maya/

Martin, Simon and Nikolai Grube (2008). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya (2nd ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson.

Schele, L., Mathews, P., Everton, M. (1999). The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs. United Kingdom: Scribner.

Skidmore, Joel (2010). The Rulers of Palenque (5th ed.). Mesoweb Publications.

Tiesler, V. (2006). Life and death of the ruler: Recent bioarchaeological findings. Janaab’ Pakal of Palenque, 21-47.

Tiesler, V., Cucina, A., & Pacheco, A. R. (2004). Who was the Red Queen? Identity of the female Maya dignitary from the sarcophagus tomb of Temple XIII, Palenque, Mexico. Homo, 55(1-2), 65-76.

Yunus Khan, T.M., Atabani, A. E., Badruddin, I. A., Ankalgi, R. F., Khan, T. M., & Badarudin, A. (2015). Ceiba pentandra, Nigella sativa and their blend as prospective feedstocks for biodiesel. Industrial Crops and Products, 65, 367-373.

Further Reading

Colas, P. R. (2003). K’INICH AND KING: Naming self and person among Classic Maya rulers. Ancient Mesoamerica, 14(2), 269–283.

García, E. V., & Tiesler, V. (2022). Royal Bodies: The Life Histories of Janaab'Pakal and the “Red Queen” of Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico. In The Routledge Handbook of Mesoamerican Bioarchaeology (pp. 348-363). Routledge.

Gronemeyer, S. (2006). Glyphs G and F: Identified as Aspects of the Maize God.

Jiménez, Maya. (2016 August 19) "Palenque (Classic Period)," Smarthistory. Accessed 2024 March 26. https://smarthistory.org/palenque/.

Scheie, L. (1991). A new look at the dynastic history of Palenque. In Supplement to the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Volume 5: Epigraphy (pp. 82-109). University of Texas Press.

Wagner, Elizabeth (2006). "Maya Creation Myths and Cosmology". In Nikolai Grube (ed.). Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht and Matthias Seidel (assistant eds.). Cologne: Könemann. pp. 280–293.

Music in Podcast:

'Clarion' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au'Soar' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'Wayfarer' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'Age of Wonder' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'Chasing Daylight' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au

'The Great Sea' by Scott Buckley - released under CC-BY 4.0. www.scottbuckley.com.au